As interest in Islam has rocketed in the West since 9/11, the broad rubric known as Islamic art has become the veritable flavor of the day. Islamic art collections are attracting massive funding in the hope they can act as a bridge to straddle the cultural divide. Politicians and museum directors have picked up on ‘Islamic art’ as an attractive counterpoint to the terms ‘Islamic terrorism’ and ‘Islamic fundamentalism’ spewed out by the news media. From Los Angeles to Athens, Western museum holdings are being reshuffled, refocused and renovated, so that the Islamic collections now find their place alongside Greek, Roman, and Egyptian antiquities at the forefront of the museum world.

But the politics belie the fact that ‘Islamic art’ is not simply the pretty face of Islam. It is in fact a confusing label for a vast and varied field. ‘Christian art’ denotes objects used in religious contexts or with explicitly religious subject matter. Objects embraced by the umbrella term ‘Islamic art,’ however, are dramatically different, often having a very loose relationships with religion. Islamic art embraces a huge diversity of objects, and recognition of that diversity is fundamental if the promotion of the field is not to become another dangerously reductionist exercise. As Tim Stanley, head of the Middle Eastern section at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), writes, “Although we call it ‘Islamic’ art, it is not so much the art of a body of believers as the art of a broad and complex culture. How then do we justify this name?” Curators are well aware of this question, which was hotly debated at the Louvre’s ‘Musée à Musée’ conference in May.

Islamic art is a Western label that became popular after the Second World War (in the 1930s, ‘Muhammedan’ or ‘Saracenic’ art — think crusades — were still current). Its scope ranges from Islamic Spain to Mughal India, and its time span runs from the dawn of Islam to the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Patterns of influence weave their way through the field to which it refers, and despite pressure from certain quarters to break it down into geographical entities (Spain, Anatolia, Iran, and so on), a strong case can be made for approaching these works as a group. From the beginning, however, the explicit religious connotation hovered uncomfortably over a broad field that, in the words of one American curator, is “not exactly religious … nor secular.”

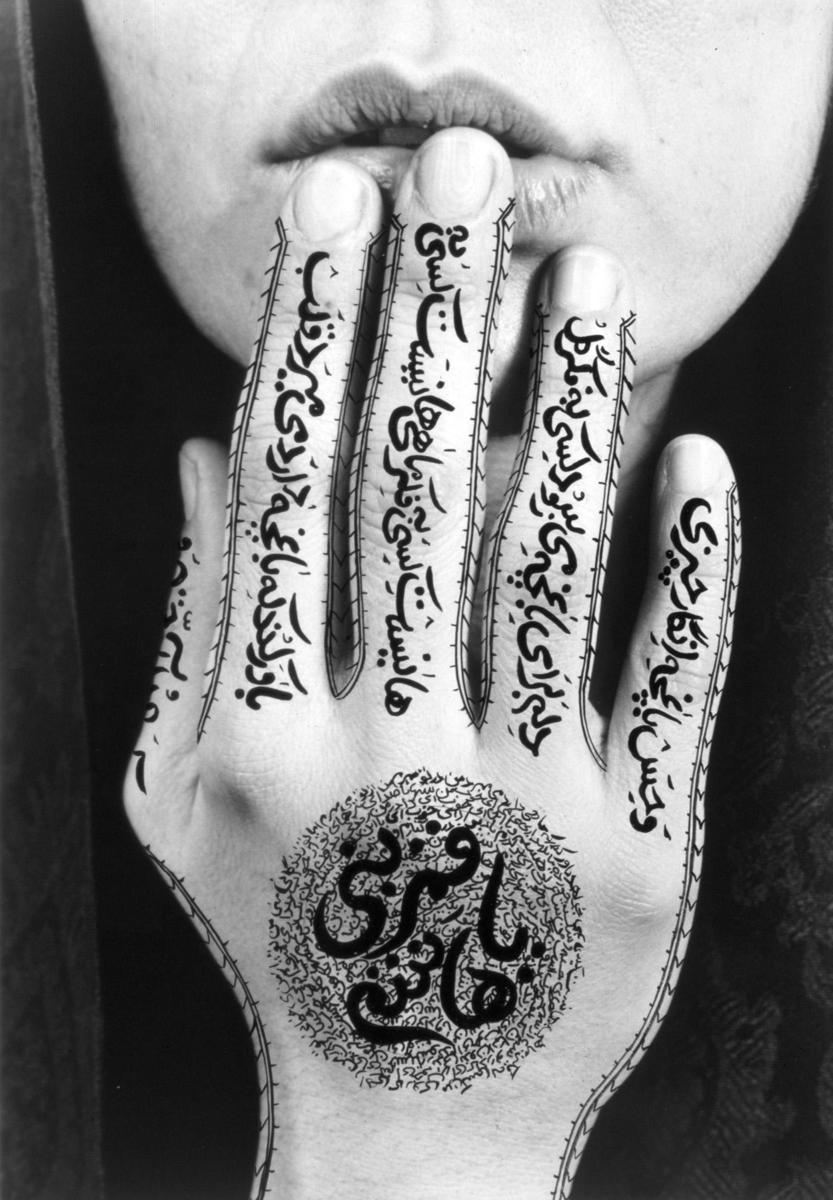

Modern catalogues of Islamic art perform linguistic acrobatics to define the term and explain how Islamic art may, or may not, directly reflect, or have been influenced by, Islam. Most curators now define it as art produced where Islam was the dominant religion. According to this definition, Iranian-born New York artist Shirin Neshat would then be producing ‘Christian Art’ — an absurd assertion, but one that seems less strange when you consider the wealth of Christian objects produced in the Middle East on display in ‘Islamic’ collections. ‘Art from Islamic lands,’ a term used by the recent Khalili Collection/State Hermitage Museum exhibition in London, is less loaded and museums are gravitating towards it. With constant pressure from the dissatisfied, the next few years should see more helpful, albeit longer-winded, titles appearing for these collections.

Facing the quagmire of museum politics and tightly defined department parameters, some curators are resigned to the title ‘Islamic art.’ Dan Walker, head of the New York Metropolitan Museum’s Islamic Department, will stick to it but is committed to launching an educational offensive that gives “full credit to the various cultures who have their own way of doing things,” and is determined not to treat Islamic art as “a monolithic entity with subtle variations.” His plans are impressive and address the issues at stake, but it is questionable whether educational efforts can win the battle when the term itself immediately heads people off in the wrong direction.

London’s British Museum recently ‘refocused’ its Islamic Gallery. One rainy Saturday I went along to take a look. Standing in a room with objects from countries as disparate as Spain and India, anything from ten to 1200 years old and including an illuminated Qu’ran, Turkish tiles, and some fairly naughty Persian miniatures, I read a display near the entrance headed ‘What is Islamic Art?’ The curators tackled the issues of diversity, a multiplicity of cultures, individuality and so on, and ventured a definition near that mentioned above. Yet many visitors walked past without a glance, making their own assumptions from the term itself.

Ironically, because of the term’s reductionist convenience, Islamic art is attracting funding for large-scale renovations, which in turn is giving curators a unique opportunity to rethink the way Islamic art is seen. Museums are debating the relative merits of geographical, chronological, or thematic displays as they cater for new and larger audiences. The relabeling and rearranging at the British Museum was part of a move to increase ‘accessibility,’ an aspect important to the museum’s new director Neil MacGregor, who has opened up the museum’s galleries to new audiences, while still retaining the appeal to scholars.

Over ten major museums worldwide are now renovating their Islamic Art galleries, some on a spectacular scale, and the principles of ‘education’ and ‘accessibility’ underlie most projects. Certain museums are removing Islamic objects, previously housed in an assortment of wider geographical (Near Eastern, Indian) or thematic (textiles, manuscripts) locations and displaying them in isolation. The new Benaki Museum in Athens has chosen to focus exclusively on Islamic art and has moved its collection into two nineteenth-century houses in the center of the city, which opened in time for this summer’s Olympics.

The multimillion dollar renovation at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, scheduled for completion in 2008, looks in the opposite direction but shares a motivation: to enhance the profile of the objects in question. Unlike the Benaki, the Met has had a separate Islamic department since the 1970s and is now concerned to place Islamic art within the context of universal culture, “side by side with related works from other cultures,” according to the director, Philippe de Montebello. The renovation will allow visitors to explore the influence of Islamic art on Western art and architecture, a popular new seminar topic for many museums.

The V&A in London is also keen to focus on cross-cultural influence in its new gallery. The museum recently received a spectacular $9.7 million donation from Mohammed Jameel, president of the Abdul Lateef Jameel Group, for a new gallery of Islamic art, scheduled to open in 2006. In an unusual twist, he also donated a substantial sum for a tour of around 120 of the collection’s best objects to the US and Japan.

Touring and temporary exhibitions are scheduled for many collections as renovations get under way. Thirty of the Met’s star objects, including important finds from Nishapur in eastern Iran, are on display at the Louvre until April 2005. But while playing host to the Met’s collection, the Louvre has been formulating its own grand plans. In February it announced a scheme to glass over the Visconti Courtyard to house its Islamic collection, only a fraction of which is now on display in underground corridors. This ambitious project, which will cost $60 million and take five years to complete, has the personal support of President Jacques Chirac. In 2002 he applauded the creation of a Department of Islamic Art in the Louvre that underlines “the essential contribution of Islamic civilization to our culture,” and personally welcomed museum directors at the Louvre’s May conference. Minister of Culture, Jean-Jacques Aillagon, said the development “obviously has a political dimension. It’s a way of saying we believe in the equality of civilizations.” On a scale of generalizations, the phrase ‘Islamic civilization’ puts ‘Islamic art’ in the shade. The sentiment is a positive one, but is another example of the presentation of the Middle East, or the ‘Islamic world’, as a monolith, and one uniquely driven by religion. While this continues, Islamic art collections will be hard-pressed to close the cultural divide.

London may soon be home to the collection of Nasser D Khalili, an Iranian-born London resident with an intimate understanding of the links between America, Europe, and the Middle East. In over thirty years he has amassed one of the largest and most important collections of Islamic art in the world. His 20,000 objects (twice the size of the Louvre’s collection) include the largest group of Islamic manuscripts in private hands. Khalili has revealed that he is about to start looking for premises and hopes his museum will be established “in the next five years.” His aim, he said, is to use art and culture to create “goodwill between the West and the Muslim world.” Khalili feels committed to Britain and is disappointed that, until recently, Muslim governments paid little attention to their cultural heritage. He told me that when he began collecting in 1967, moving from Iran to New York when prices were low and neither Muslims themselves nor Western museums appreciated their value.

Times have changed, however, and the old Western centers of art may be swiftly becoming the poorer relatives of their Middle Eastern counterparts. Sheikh Nasser al-Sabah of Kuwait has a phenomenal private collection of Islamic art and has established a collection of over 20,000 objects for Kuwait’s National Museum. A colossally rich collector, he has been a discerning contender at Islamic art sales for years but has recently met with serious competition. Sheikh Saud Al Thani is collecting for Doha’s new Museum of Islamic Art, designed by IM Pei and the first of five museums scheduled to open in Qatar’s capital. The scale of his recent acquisitions has driven prices through the roof. Christie’s reported its highest ever total for a sale of Islamic art (£11 million) at an April auction that saw Al Thani, represented by a team of agents, pay £901,250 for a Mughal agate-and-garnet fly whisk handle valued at £8000. The Sheikh bought 350 of the top lots in April’s Islamic sales, and no European or American museum can compete. With interest in Islamic art backed by such buying power, the Middle East can look forward to a world-class museum while the art world as a whole experiences the knock-on effects of Islamic art’s rising profile.

Contemporary art from the region, however, remains within grasp and a few Islamic art departments have begun collecting, an innovative decision but one that further complicates labeling. The British Museum is unusual in actually displaying contemporary pieces in its Islamic Art gallery. On show are ceramics by Tunisian artist Khaled Ben Slimane and a work by another Tunisian, Nja Mahdaoui. The repeated words and phrases that cover Ben Slimane’s ceramics have strong Sufi associations, and his works ironically portray one of the collection’s most overt relationships with Islam, but hover on the boundaries of Islamic art. Mahdaoui’s piece explores calligraphic vernacular through shapes that are inspired by Arabic letter forms but hold no textual meaning. In a room where Arabic script is just ‘squiggles’ for many viewers, his work creates an interesting interplay with the neighboring religious texts and leaves from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh— and questions the relationship between object and meaning in a room where text signifies nothing to many of its audience. These ‘contemporary’ pieces, a label with its own assumptions, bring into focus how the term ‘Islamic’ overshadows art to which it is applied.

So as the term becomes strained, and curators debate alternatives, the very words ‘Islamic art’ attract money and attention from governments and Middle Eastern benefactors. As its profile rises, Islamic art thus finds itself at a crossroads, and current developments will profoundly affect how it is framed for audiences in the future. Museum heads and politicians emphasize the importance of ‘Islamic culture’ and ‘Islamic civilization’ and ironically, under the shadow of these unwieldy terms, curators finally have the opportunity to reshape their collections and explore the individuality and diversity of the works and cultures that produced these treasures.