Long before the experience of publishing my novels, my son, then seven years old, came to me one day with an Arabic reading book asking me to “translate” a phrase he did not understand. “Translate this sentence for me please,” he said. He used the word “translate” and, of course, he wanted me to “explain” with colloquial or spoken Arabic, or amiya, the sentence written in classical Arabic, or in fussha. My son did not understand at that age why Arabic is two “languages,” as he put it, while the French that he began studying in his early years is one language.

In an article published a few months before his death, the eminent Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said argued that the debate on the need to reform Islam, as well as the Arabs and their language, reflects an extraordinary lack of the daily experience of living in Arabic. Said was perfectly correct by referring to the Arabic language as an experience of life, something we live and live in.

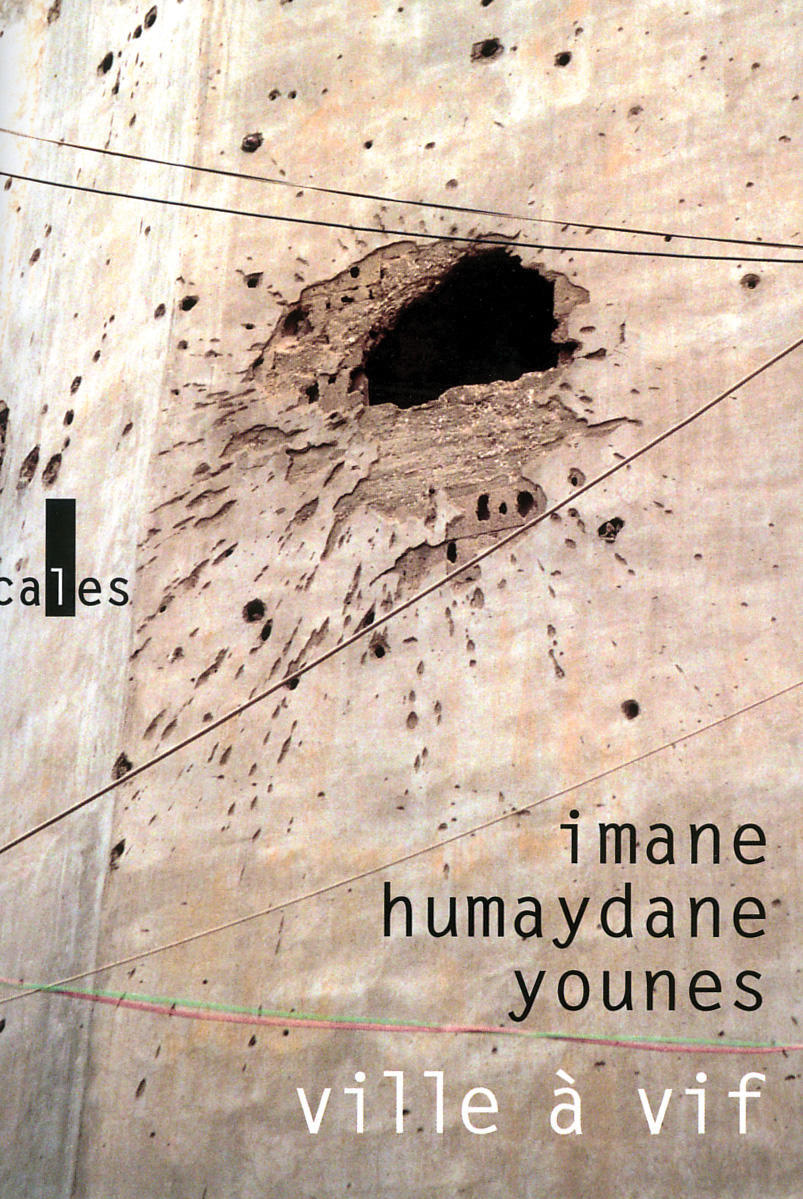

Writing about my experience with the Arabic language, be it fussha or amiya, does not only stem from my being a female Lebanese writer (novelist), but also from my experience of the cultural, political, and social changes Lebanon witnessed during the last three decades of the twentieth century. These changes, no doubt, affected our language. However, what we have now as a modern written language goes back to the changes Lebanon has gone through from the beginning of the last century until the present.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, there has been an ongoing debate on our language in the Arab world. At that time there was a strong notion that the classical Arabic language would face a destiny similar to that of Latin. Both supporters and enemies of classical Arabic had the same view. Those who were pro-Arabic feared such a destiny because to them, the Arabic language was a symbolic representation of their religious and national identity. Needless to say, the Qur’an “was descended” in Arabic and is therefore seen as the principal and sacred source of the language. Such ideological arguments were used by the many defenders of classical Arabic, but equally by its enemies, who viewed the language as being exclusively identified with religious Islam as well as a form of Arab nationalism. They wanted to abolish classical Arabic and to construct cultural and political identities far removed from the language and its nationalistic implications. Is that debate over amiya and fussha still alive? It seems that the debate has lost its spark and that both fussha and amiya have changed.

Around the mid-1950s in Lebanon, for example, the Lebanese poet Said Akl argued that, like Latin, classical Arabic was a dead language and should be reformed and replaced by amiya. Akl published a book in amiya Arabic using Latin script instead of Arabic. However, Akl’s initiative (he is still alive at ninety years of age) remained an isolated attempt.

In the past, the fussha and the amiya very seldom met. Fussha was used in the media, in political discourse and even in conversation among leftists, nationalists, and intellectuals when talking about politics and ideology. On the other hand, amiya was seen as the language of feelings, emotions, love. We never expressed love or made love in fussha, but we did use fussha while talking in a political party meeting or in a conference. ’Amiya was the language of the ‘quotidian,’ while fussha of the discourse.

Nowadays, however, the dual language does not seem as divided as it was in the past. Fussha has lost much of its eloquence, and amiya has lost some of its independence and peculiarity. Perhaps Gibran Khalil Gibran, the Lebanese-American writer, poet, and artist, expressed perfectly the idea of bringing together fussha and amiya in an article he wrote in the mid-1950s, about the future of the Arabic language. He argued that there must be a third language that grows out of people’s changing lives and ways of expressing themselves. To Gibran, this third language — which Edward Said called the modern fussha — must be a combination of feelings and of thoughts.

The media has played a major role in modifying and modernizing the fussha that both Gibran and Said wrote about. News broadcasts on radio and television are in fussha, but at the same time are closer to amiya. However, sometimes television stations broadcast programs with dialogues oddly conducted in fussha. The practical reason for this is that these programs are mainly targeted to the broader Arab audience who cannot follow the different dialects of each Arab country.

Following the Lebanese war, local television channels started broadcasting a Mexican series dubbed in fussha. The series is similar to American soap operas such as Dallas, Dynasty, or The Bold and the Beautiful. It was very funny for an ordinary Lebanese audience to watch characters leading super-modern, cosmopolitan lives, while talking in fussha. It was something new for us to be able to express love or hate and to insult in fussha. Now, whenever someone is speaking heavily classical Arabic in Lebanon, they say that he or she is speaking Mexican! Lebanese television stations were obliged to choose fussha, instead of the Lebanese amiya dialect, in order to be able to sell the dubbed series to other Arab countries. It is difficult to understand the dialect of each Arab country, as it varies from one country to another. In this sense, classical Arabic unites Arab countries. And when people from different Arab countries meet, fussha is used in order to communicate.

My very personal argument is that my generation in Lebanon was deeply influenced by the young Lebanese actor, composer, and theater director, Ziad Rahbani (son of the famous Lebanese singer, Fairuz). Born in 1957, Rahbani lived his adolescence and some years of his adulthood witnessing the Lebanese civil war (1975–1990) and the massive destruction it caused. The war destroyed social, political, and mainstream cultural values. These changes were reflected in language too. The modern Lebanese novel was born out of this destruction, representing a new way of writing and expression. Though he is not a novelist or a writer in the wide sense, Rahbani contributed greatly in his way to Lebanese theater, by bringing amiya to the political discourse that was occupied by fussha. He also played a major role in bringing the language of the intellectuals to amiya. Rahbani did not make a compromise between amiya and fussha, as the Lebanese writer, Maroun Abboud, did at the beginning of the twentieth century. On the contrary, he rather destroyed the eloquence and the sacredness of fussha by presenting it as the language of lies; or the language of the non-lived, or the non-lived-in. Rahbani was not the only artist who contributed to the debate of the fussha and the amiya, nor will he be the last.

While writing my first novel B…mithl bait mithl Beirut (B…Like Beirut), I had to stop several times in front of a word I wanted to use, feeling that it might not be understood by non-Lebanese Arab readers. However, this was a part of the dilemma I faced. I was brought up in an environment where street language, or the everyday ordinary amiya words, were not very welcome in writing. But I am a daughter of the civil war too, and this situation helped me overcome the sacredness and taboos of the language in my text. While writing dialogues, I feel that fussha does not fit or reflect what my characters really want to say. Maybe that is why some novelists avoid using dialogue in their writings. They cannot imagine themselves writing amiya. This is mainly due to the deep idea that they have about writing, which is seen as a sacred task that aims at bringing their writings near to the old scripts.

I use dialogues and I have the courage to use amiya in places where it looks awkward to write what a character says in fussha. I always see language as a living thing, or a living process. I live in it and it lives in me. I cannot imagine myself writing a word that I do not feel. I do not feel many of the old, eloquent, and classical Arabic words and in this sense I have never had any loyalty to the language. I do not see it as a sacred script. To write with creativity, one must cheat on language, betray it, mold it, and try new things in order to take the language out of its deadly forms. This happens usually when I start writing. After a while, I feel that I am going on a long journey accompanied by a language that is continuously created and subsequently destroyed. Now, while writing my third novel, I do not find any difficulty in moving from amiya to fussha and I do not see it as a problem. Quite the contrary, moving from fussha to amiya, and vice versa, gives me a freedom of expression with much richer images and meanings, something that no other language can give me.