A few months ago, the artist Farhad Moshiri received a curious email. “Hello, Mr. Moshiri,” it read. “I wish that you would stop producing art.” A few weeks later, an article in a prominent online arts magazine derided a body of work he showed at the Frieze Art Fair as “toys for the anesthetized new rich.” The author, a fellow artist and gallerist, declared the assembled pieces — a series of elaborately embroidered birds sparkling in DayGlo colors, titled Fluffy Friends — “an insult to all brave Iranians who have shed their blood for more freedom.” In a final scabrous blow — it was only a few months after the contested presidential elections of 2009 and all the bloodshed that ensued — the author wrote that the artist had “amputated his Iranian heart and replaced it with a cash register.”

Moshiri, who lives and works in Tehran, was delighted. “I cherish these letters,” he told me. “They turn out to be like the diplomas people hang. I keep them close.”

At no taller than 5’5” — or, if you include the swirl of curly black hair that falls over and around his head, 5’6” — Moshiri seems an unlikely candidate to inspire such virulence. With his thickly rectangular black eyeglasses and ears that stand out at perpendicular angles to his head, he resembles Woody Allen, had Woody Allen been Iranian. His manner, detached and marked by a highly developed irony, rarely betrays anxiety, anger, or even pleasure. He has the social instincts of a hedgehog: he rarely leaves his own house or studio, is only occasionally seen out at exhibitions and openings, and is famously loath to attend art parties. He has been known to spend entire days in bed — doing what, nobody really knows.

Moshiri’s artwork, on the other hand, is often very big, very loud, and very present. Quoting from the languages of advertising, fashion, and even occasionally religion, it seems to yell, “Notice me!” “Covet me!” And finally, “Oh, please, please buy me!” With such titles as Run Like Hell, I Forget You Forever, and Three Homes Is Where the Heart Is, it also very often makes you laugh. When contemplating Moshiri’s works — spectacularly beautiful objects made of smaller spectacularly beautiful objects — our own reactions emerge as objects of scrutiny and wonder. It is, at the risk of reducing it all to a one-liner, artwork in seductive packaging that is in turn about seductive packaging. If you don’t enjoy the spectacle of someone having their cake — or is it yours? — and eating it, too, you may very well be annoyed by the fact that his work often sells for hundreds of thousands, even a million, dollars.

I first met Moshiri in Berlin in 2003 at an exhibition staged at the House of World Cultures under the pleasingly opaque title ‘Far Near Distance.’ There was a bevy of Iranian artists there — Khosrow Hassanzadeh, Marjane Satrapi, Ghazel — many of them members of a stable cultivated by Rose Issa, a Lebanese-Iranian curator who has probably done more than any other person to usher Iranian artists onto the international stage.

We met at the cocktail bar after the opening, and after exchanging pleasantries about the cold Berlin weather, I decided that we probably would not be great friends. I complimented him on the fact that his work, a series of gilded furniture pieces, was on the cover of the exhibition catalog. It was, as I understood it, a sculptural response to the prevailing Tehran decor vernacular of the times. “That’s great!” was all I could think to say. He remained silent. I got along better with his wife and sometime collaborator, Shirin Aliabadi, a woman with well-kept bangs that hung over a large section of her face. But after that, I kept running into him, especially in Tehran, where people would sometimes refer to him as “that pottery guy.”

The pottery, as it happens, were paintings — a series of works on canvas Moshiri had started in 1999, inspired by old ceramic jars that he had seen in a museum in his hometown. The mottled surface of the jars in his paintings were overlain with text. The words, which one might well presume would be the oracular stuff of Persian mysticism, were in fact drawn from popular sayings — the kind you sometimes find lovingly inscribed on the backs of long-haul trucks, like “Say Congratulations,” or “Only You,” or “The Past Is Past.”

Despite their cheek, the canvases were probably mostly experienced as beautiful objects. “I think it’s safe to say most people didn’t get it,” Moshiri says. Perhaps adding to their cachet, the canvases were vaguely evocative of the Saqqakhaneh school, an Iranian modern art movement of the 1960s and ’70s that was inspired by Persian calligraphic traditions, and has been called “spiritual pop art.” Artists such as Parviz Tanavoli and Hossein Zenderoudi were the movement’s patron saints.

In any case, the jar canvases were a hit. By 2001, the artist and gallerist Fereydoun Ave offered Moshiri a show in his space in Tehran’s central Vanak Square, and before long, the pottery was hanging on the walls of many of Tehran’s better-known art collectors. The series also introduced his distinctive relationship to text as an element of his practice — not exactly conceptual, but something far simpler. “Text became a shortcut for me to reach a certain emotional level. I noticed that text had an effect on people that an image never could,” he says now.

Tehran of the early 2000s was a stimulating place to be for many artists. Under then-President Mohammad Khatami, the oft-smiling figure whose previous job had been running a library, it was easy to imagine that you were living just about anywhere but the Islamic Republic (as long as your work didn’t engage politics). Artists got away with a lot. Alireza Sami Azar, a finely mustached architect-turned-art-dealer, had recently been appointed head of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, a modernist structure erected under the patronage of Empress Farah Diba in the 1970s. Soon, exhibitions of local artists were being held alongside international exhibitions. I remember seeing works by Henry Moore, Anthony Caro, Anish Kapoor, and Damien Hirst in Tehran at an exhibition of twentieth-century British sculpture back in 2004. A conceptual art show was launched, a cultural center in the north of the city reopened, and artists increasingly began to occupy public space — from roadsides to half-finished high-rise buildings to, in one unique case, the courtyard of the city’s central mosque. And of course, throngs of international curators passed through — mostly to assemble the sweeping Iranian group shows that would become de rigueur. Whatever you made of it all, things were undeniably happening.

It was also around this time that Tehran experienced a windfall of new wealth following the gradual opening up of the economy — under Khatami and his predecessor, the wily chameleon-like businessman Hashemi Rafsanjani. Money literally reshaped the face of the city: suddenly, Dubai-style facades were erected all over the city’s north side in a strange ersatz version of Beverly Hills. Neon-lit coffee shops with confusingly exotic names such as GRAFFITI and LATEX opened on every block. People drove around in circles checking one another out from their fancy car windows in the posh northern Tehran neighborhood of Elahieh. Nouveau-riche giddiness was the zeitgeist of the times.

Rather than retreat in horror, Moshiri, who today lives in Elahieh, reveled in the changes. He mined them. The high-rises, the consumer detritus, the nose-job fetish — it became his raw material. “People were even putting up mirrored disco glass in their simple village homes,” he muses now. His next projects included a photographic series of monumental Tehran residential facades, each in more heroically poor taste than the next. And then came work on what he refers to as “found objects” of the city: talismans of Persian culture colliding with decidedly Western tropes. A stylistic frottage, if you will. This was the land of Kabooky Fried Chicken and Pizza Hat, the best sort of Esperanto. It was too good to pass up. Even watching Iranian state television provided him with endless fodder. His work was wholly informed by the world coming up around him, and in some ways, continues to serve as an X-ray of it.

Farhad Moshiri was born in 1963 in the southern Iranian city of Shiraz — famously the birthplace of the great poets Saadi and Hafez, the seat of the Persian Empire during the Achaeminid Empire, and more recently the playground of Farah Diba as she orchestrated an avant-garde arts festival there from 1967 to 1977. In those years Merce Cunningham, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, and many more came and went, staging events with the full patronage of the royals.

Moshiri was a wee young man when these strange manifestations of art took place. “I’d hear people laughing about the ‘high art’ in Shiraz,” he remembers. “It was mostly negative. That kind of art appalled and shocked people. The story was that socialites would come to Shiraz to see these weird things. As a kid I’d hear people mimicking the performances — the noises, the positions. There was a story about someone shooting rubber bullets up their ass and calling it art. I think it’s fair to say the Pahlavi regime seemed pretty out of touch.”

Moshiri’s father, a businessman, ran a string of cinemas in Shiraz, mostly showing standard spaghetti westerns awkwardly dubbed into English. Farhad loved the movies. He was also skilled at drawing, which his father encouraged. At school, where he failed many of his classes, his Indian-born teacher and his classmates would call him “big fool, little fellow.” He spent most afternoons riding his bicycle through the little desert town and eating Mars bars. As the Revolution of 1979 rolled around and the shah, his pretty wife, and all that avant-garde-ism was on its way out, Moshiri was shipped off to another desert town, called Idyllwild, some two and a half hours from Los Angeles. There, he ran around with the children of dysfunctional celebrities at a boarding school on top of a mountain.

He moved on to CalArts after that, where John Mandel was his advisor. Conceptualists John Baldessari and Michael Asher were also on faculty, as was Don Bukla, the inventor of the analog modular synthesizer. “Once I saw that instrument, I nearly fell over backwards,” he said. “An entire wall of shimmering metals and flashing LEDs was something out of sci-fi movie — it was Plan 9 from Outer Space. From then on, I stopped going to class. When I did go, I was a walking zombie.” Not going to class caught up with him, and in his third year Moshiri was called in to speak to the dean. “They gave me a simple choice. Show up to class, or get out. So I left.”

From there it was a short trip to various odd jobs — making sculptures out of liquid latex (the singer Billy Idol bought one, but later returned it) while moonlighting as an inventor (his claim to fame was a magical disappearing pen). At the same time, a modest gallery scene was coming to life in Santa Monica, and Moshiri would go to openings — “mostly for the free food.” In 1989, he received an offer for his first show from a small and respectable Santa Monica Gallery called Dorothy Goldeen. For the exhibition, he painted the opening and closing credits of films, and it got a write-up in the Los Angeles Times. “It seems that I was slowly cornering myself into becoming an artist,” he reflects. But still, in the midst of an economic recession, money was hard to come by, and he started to think about going back to Iran — he hadn’t been there in eleven years. “Suddenly it felt like things were happening. You’d hear about how great Iranian cinema was and this or that. I thought, ‘I could do that.’ So I packed up and went.”

In Iran, Moshiri submitted film ideas to the Farabi Cinema Foundation, which was giving out grants to young filmmakers at the time. All his ideas were rejected. He worked on some animations for UNICEF, and he and Aliabadi — who had just returned to Iran after studying archaeology in Paris — made a children’s book together. He showed what artwork he had to Golestan Gallery, one of a handful of respectable galleries at the time, and was told that his work was “like a salad,” a mishmash that didn’t make all that much sense.

Out of money again, he began to craft stylized knockoffs of antique furniture, the sorts of things trendy young people might put in their new condominiums. It was around then that he encountered the jars at a museum in Shiraz. Soon enough, just about any item under ten dollars — “That was my budget”— became a potential point of departure for his work. Of course, in a country where abstraction and expressionism were widely accepted, while Duchamp was largely unknown, Moshiri’s work with found objects was confusing. But Moshiri showed the jar canvases at artist and gallerist Fereydoun Ave’s space in central Tehran, and eventually, abroad. He may have even showed them too much. “I was becoming the Pottery Barn guy,” he says now. “And that terrified me.”

One day in 2004, while planning an exhibition of furniture pieces in a gallery in Rome — by then, his decorating work had evolved into artworks covered in gold leaf — the curator asked him to think about something he could hang on the wall. With the help of local craftspeople, he commissioned his first embroideries, the kind many Iranian families hang on their own walls, depicting bucolic scenes of flowers and countryside and the like. His body of embroidered works eventually evolved into a morphine paradise of colors depicting, variously, maps of the world, a shiny crown, pint-sized cowboys and Indians, a control room, a little boy painting under the sea in an underwater suit — all whimsical, all indulgent, drawn from what one would imagine was nothing more than a little boy’s fantasy world. “I’m sure my subjects come from some childhood hang-ups that I might not have worked through. A psychologist could explain this better than me.”

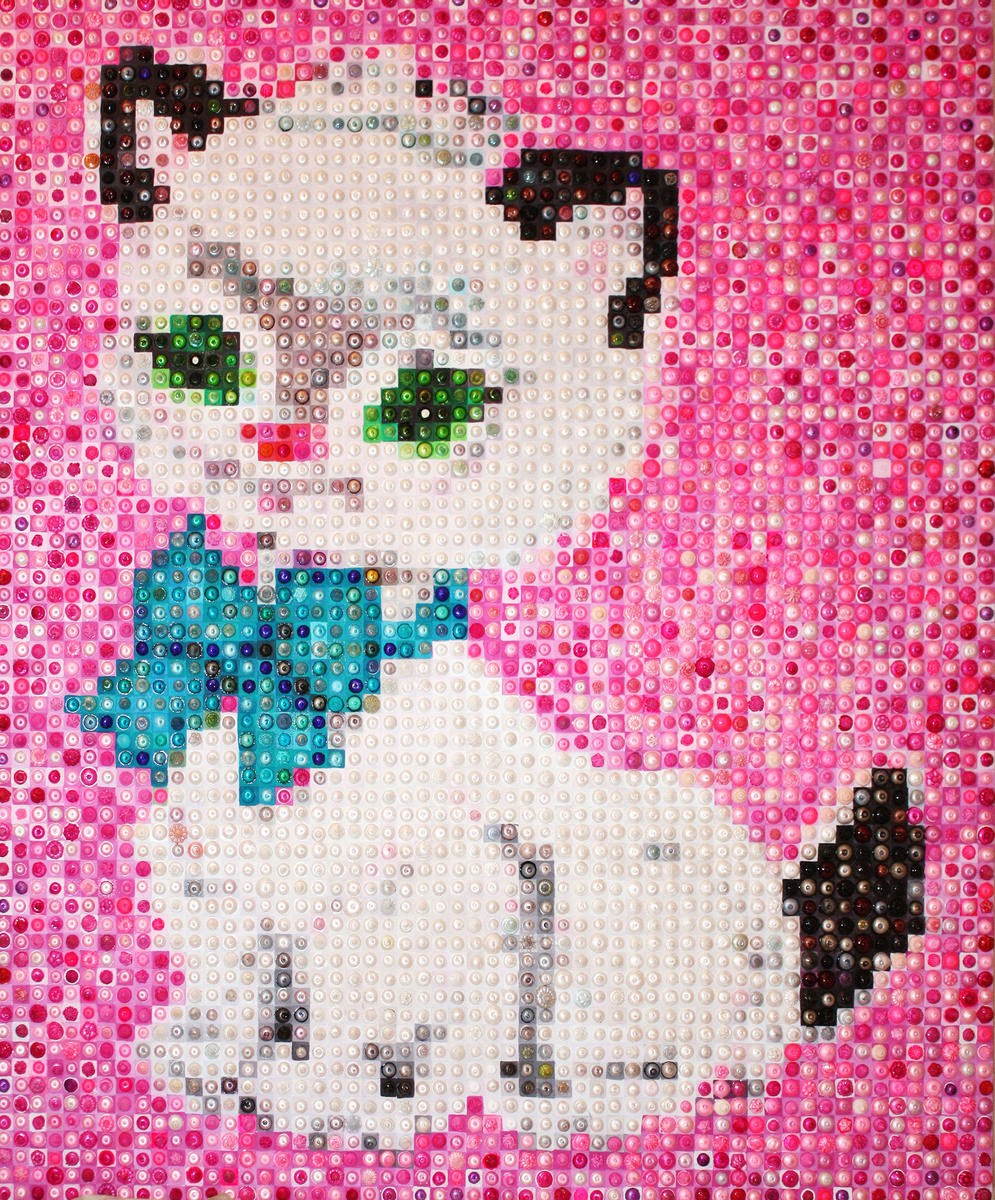

Later, he began to craft “cake paintings,” dense canvases that took inspiration from the palatial flourishes of the cakes common in Tehran bakeries. Made by squeezing paint through pastry bags, the paintings evoked all kinds of elaborate surfaces, from luscious fancy cakes to plaster-ornamented buildings. Chocolateman versus Pearlcake presents a muscly traditional Iranian wrestler made of what appears to be chocolate overlaying a ravishing pink pound cake. Others depict human profiles — seemingly drawn from hokey Eisenhower-era children’s literature — over images of ornate beds.

“I’ve found a cornucopia of materials that have become my palette,” he said. “They are my paint. They’re even more valid than paint.”

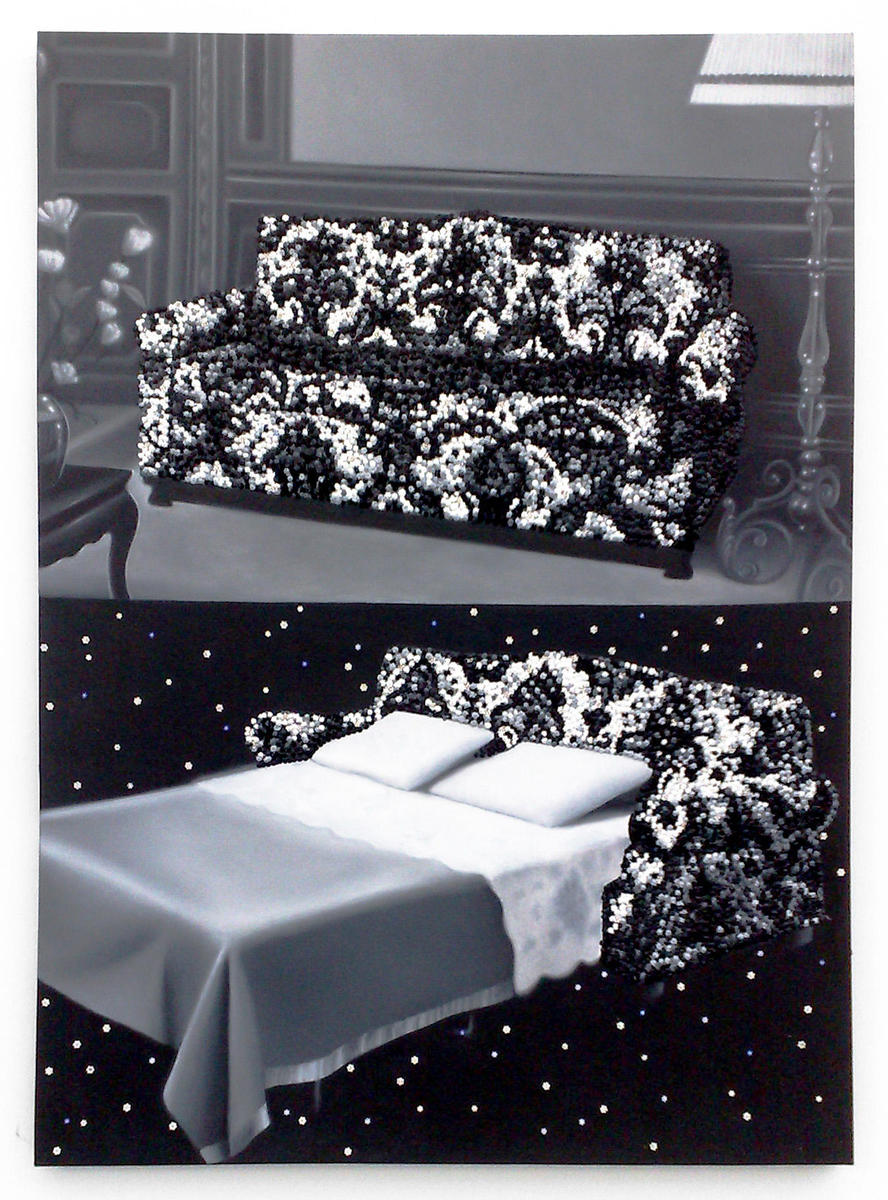

Occasionally, Moshiri invokes the self-portrait in his various titles, among them a work that involved a droopy crystal chandelier hanging over and absurdly close to a poofy chair. It is hard not to laugh. “It makes it easier for people to understand a work when you give it human characteristics,” he says. “I have paintings of couches that are self-portraits, too.”

What furniture does he really feel captures his spirit?

“I’m not a chair or a table. I’m more like a couch… that can also be a bed.”

Farhad Moshiri entered the public realm at a time when Iraneté was especially en vogue, inspiring a tsunami of terrible work. Some of the artists who rode the wave of attention stayed safely in that ethnic enclave, others moved on, and still others disappeared into the ether. Farhad, already a veteran of at least a decade of multicultural wars, carved his own peculiar route.

Take, for example, his lesser-known, but equally important, body of work produced with Aliabadi. Here, the world of Iranian products, television soap operas, and even censorship provide ample fodder for explorations of a culture in awkward flux. In their work, Moshiri and Aliabadi point out, for example, that the Iranian cola drink ZAM ZAM looks like PEE PEE when spelled in Farsi script. A popular disinfectant is called “Snow” in Farsi but “Barf” when translated to its phonetic Roman equivalent. Pages from censored women’s magazines reveal their own distinctive artistic style. Moshiri and Aliabadi have shown these inadvertent collages in their work (and sometimes as their work). Sure, it’s kind of facile. But it’s also a map of an economy of signs, translations, and lost-in-translations that speak to the contemporary condition.

Still, Moshiri’s work is not about globalization or the individual stuck between worlds, or any of that soppy East-West stuff, as much as it is about how culture is a thing that is always in progress and finally, inevitably, in the eye of the beholder. And if we accept that we live in a world in which borders are increasingly ambiguous, Moshiri’s work captures some of the stranger manifestations of that porousness to tell us a story that is as old as time itself.

There is, you might say, an important question to raise here about kitsch — especially for an Iranian artist who came of age in Los Angeles and whose consumption and representation of Iranian vernacular is so unabashedly garish. Few take Jeff Koons to task for misrepresenting the Easter bunny or for defaming American bad taste. But Moshiri’s art inevitably raises uncomfortable questions about taste and faith — both bad and good — in Iran as in the West.

In a way, Moshiri attempted to address this problematic in 2005 by putting on a curatorial hat in a small Chelsea gallery called Kashya Hildebrand. 'Welcome’ was the name of the show, and it included some of Moshiri and Aliabadi’s work — re-edited takes from Persian soap operas as well as a series of decorative plates — along with images of men’s belts by the photographer Peyman Hooshmandzadeh and the works of a popular street photographer named Bahram Afandizadeh, who normally serves Tehran’s Afghan community. In its own way, the show pushed back against the aesthetic language that America was becoming familiar with when it came to Iranian artists. And it was funny, side-stepping the didacticism of so many shows that take the art market as their subject.

Writing in the New York Times, the critic Holland Cotter aptly wrote of the assembled works in 'Welcome’: “They are self-studies, and they turn the show itself into a kind of cultural self-portrait. The portrait is shaped by the varied forms of modernity it encompasses, and by what it resists, namely a particular kind of self-exoticizing that the international art market tends to reward.”

There is a manner in which the discomfort Moshiri’s work evokes in some circles mirrors the sensitivities brought on by the peculiar geography that is Dubai — situated just one hundred miles from Iran across the Persian Gulf. Strangely, the artist’s fortunes have closely tracked the dramatic ascendance of that city, a place that inspires wildly diverse reactions, depending on one’s ideas about history, class, and, above all, taste. After all, it is in that glittering Xanadu — where Moshiri is represented by The Third Line Gallery, and spends more and more time — that he came to be known as the auction-house golden boy, the paladin of Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams.

In May 2006, Christie’s held its inaugural sale in Dubai, outpacing all expectations and tripling pre-sale estimates. It was not long before Bonhams and Sotheby’s followed suit. By 2007, Christie’s was holding two sales per year at the Emirates Towers Hotel, and in October of that year sold $12.6 million of Arab and Iranian art in one evening alone. Moshiri was featured in these sales and in 2008 broke the auction record for a painting by an Iranian artist, with a work with the Farsi word for LOVE embroidered in Swarovski crystals and gold sequins. There was an irony in the fact that Iranians such as Moshiri could go on living at home, while being within close reach of the flush markets of Dubai. Suddenly, many observers of this young market wondered if the auctions were not distorting the field. And still others called Moshiri a sellout — though often finding it difficult to articulate exactly what he was compromising. As ever, there was the discomfort of seeing someone get fabulously rich from making art. I once asked him if he ever thought of disengaging from the auction market and all its accompanying baggage.

“The refusal to participate wasn’t interesting to me. It wasn’t effective,” he said. “Sure, there were moments, especially when the auction houses would come to Iran to pick up work, that I would be frustrated. But by not entering, what kind of statement are you making? You disappear. Of course, the auction also means that you hope work you made ten years ago, and wish would disappear, will not reappear. But it’s still impossible to withdraw completely, or it was for me.”

On the subject of Dubai, Moshiri is enthusiastic. “To find myself in that position, to witness a modern city being built up, was incredible,” he said. “Things were adventurous, my imagination was running wild. The energy was incredible. To imagine an aesthetic that is completely run out of this world. Nothing was held back. Everything was unchained.”

Just as Dubai is routinely derided as all fake, all the time, an oasis of plastic, so too is Moshiri’s work. For him, perhaps, the complaints are of a piece:

“An artificial make-believe lifestyle fascinates me. I use fake diamonds in paintings, and that’s somehow related to the fact that some people want to believe that they’re real diamonds. Art is about illusion. It’s a manufactured idea in order to reach a certain illusion and expression via artificial methods… so suddenly the whole thing makes sense. We’re all in the same boat.”

It is true — at times, the lines between fake and real in his work become impossibly blurred. When showing his gilded vitrine series at the Sharjah Biennial in 2005, for example, he pleased two passing sheikhs, who appeared visibly disinterested in the postmodern stuff of international biennialdom that surrounded them but who nodded admiringly at Moshiri’s glittering objects — finally, something they liked!

In the end, Moshiri will always be — for some people at least — the guy who made fluffy DayGlo birds out of sequins while the revolution came and went. And indeed, he is not not that. Art, after all, may be about illusion, and it may be a manufactured idea, as he himself puts it. It may also be, as Duchamp asserted, simply what the artist says it is. “You are what you eat,” Moshiri once told me, of his gilded furniture pieces. Celebrate him or shun him, he may remain the paradigmatic artist of the boom times.