Terrorists look good. Those scarves and the things over their eyes… it’s a good look.

—John Waters

The marrow of the bones of the wives’ legs will be seen through their flesh out of excessive beauty.

—Al-Bukhari, on the subject of a martyr’s promised virgins

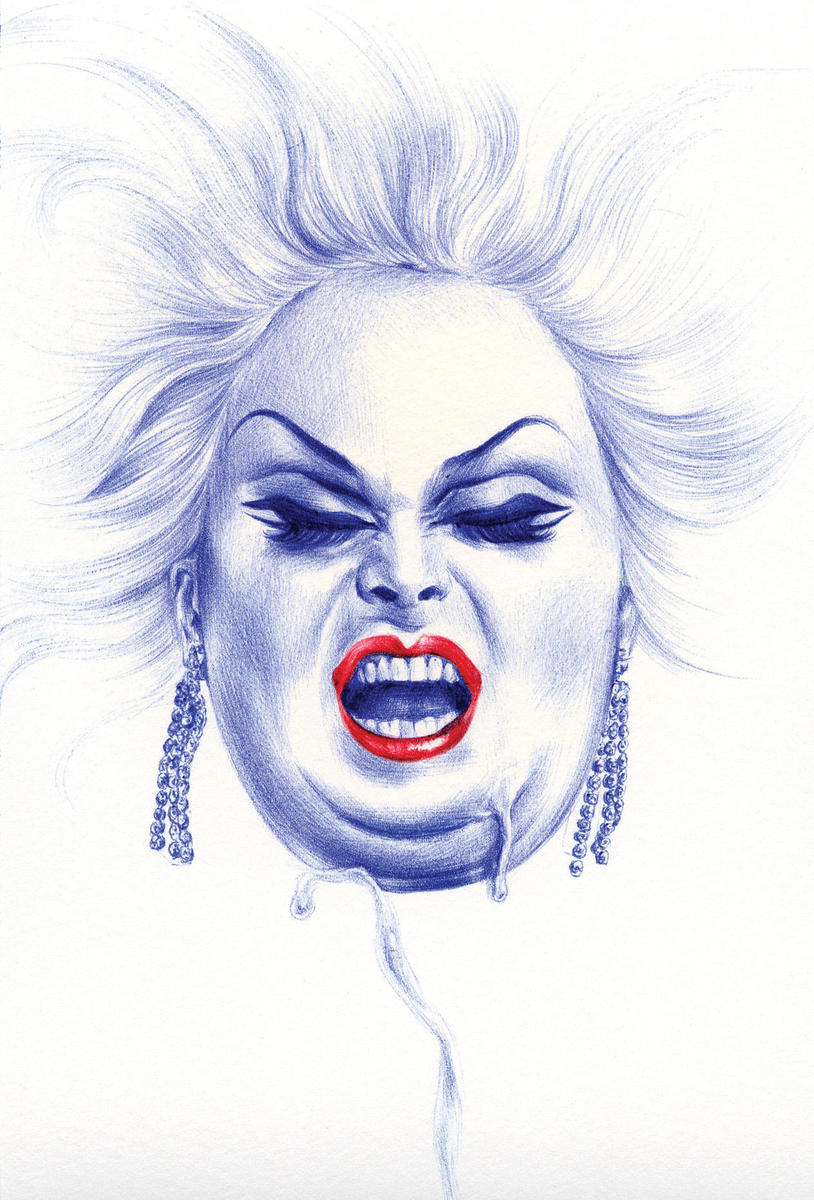

Smut is an underexposed, overdeveloped stretch of cinematic history, an aesthetic smeared with the detritus of erotic affect and empty attainment. Think Tura Satana’s faked orgasms, Russ Meyer’s empty promises. The ember of a small-town starlet’s Hollywood dream stubbed out in the carpet of an LA motel room. In smut, the interval between agency and abjection is ground down on a mirror and divvied into rails; corn syrup, mixed with real blood and splattered onto the porcelain face of Dyanne Thorne: Ilsa.

She doesn’t flinch; her crazy-eye twitches and her lucent teeth glint in the camera’s light. Her evil Nazi master plan is now complete. Katsina, an unwitting suicide bomber, has just humped the sheikh to his bloody death. “A fitting end for a man who lived by the flesh,” Ilsa tuts to Commander Adam, her CIA lapdog. He feigns disapproval. “But what about her, Ilsa?”

The year was 1976. Dyanne Thorne was the reigning queen of the Nazploitation genre, the latest offspring from the high-acid loins of men’s adventure magazines like Champion, Argosy, and Male. Her character’s name was Ilsa, but her epithets ranged from She Wolf of the SS to Tigress of Siberia to, most thrillingly, Harem Keeper of the Oil Sheiks. As for Su Ling, the actress who played Katsina, she disappeared without a trace. Only the glimmering light of her fading porn star keeps her memory alive. Before she vanished, Su Ling appeared as a sex worker in Russ Meyer’s Up! and (uncredited) as a prostitute in Farewell, My Lovely, a murder mystery about a missing “dancer.”

For all the abasement of playing prozzie, Su Ling is absolutely arresting on the screen; it’s almost uncomfortable to watch her. She radiates a strange power as she slinks in the flickering shadows of El Sharif’s palace. Her presence seems dangerous, even wrong at first, but something in her is bizarrely rosy. Su Ling is in possession of a weapon more devastating than the plastic bomb attached to her cervix. It is what feminist theorist Audre Lorde called “the assertion of the life- force of women; of creative energy empowered.” Su Ling is haunting because a transparent “life-force” emanates from her body. Like a Bukhari virgin, she almost explodes with “excessive beauty.”

This also makes her a bad actress.

Smut is no place for the erotic. Despite all her blond and buxom might, Dyanne Thorne couldn’t wield that “replenishing and provocative” force the way Su Ling did, making Thorne paradoxically the better actress. But her performance was devoid of what Lorde calls “revelatory exposure.” Thorne was a pastiche of the worn-out taboo of feminine power, while Su Ling was simply taboo.

Flanked by her waxed and greased warrior-girls, Velvet and Satin, Ilsa deploys the de-eroticizing tools of camp. She plays down her real pleasure by hamming it up, moans louder and thrusts higher so as not disturb the boundaries of fantasy. Hers is the sensual distortion of big boobs and bare buttocks, a mannequin with a whip and jodhpurs. The suppression of Eros is an important part of her job as she paces about the threadbare plot, overseeing the sadistic high jinks that take place in her harem while priming her wenches for sex and/or death.

Indeed, this is the work of camp. John Waters would never have gone anywhere if he hadn’t dyed the pubic hair blue, concealed bad acting with worse dialogue, or taken the tang off ingesting dog feces by slowing twenty-four frames per second into a few stills of Divine’s shitty smile at the conclusion of Pink Flamingos. Still, Divine’s dry heaving over a plate of fresh poodle poop was so… evocative… that first-run audiences were given special barf bags. This was a tongue-in-cheek precaution in the event that the ecstatic communion of voyeur and viewed became too much to stomach.

It was this emotive intensity, both on the stage and in films like Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble, that underwrote Divine’s persona as a self-described “drag queen terrorist.” Her power was not merely vomitorial. Divine incited heckling, licking, sniffing, singing, snogging, loathing, and laughter, often at the same time. Grotesque, sexy, and swaddled in spandex, Divine’s riotous presence onscreen was that of the ultimate Other, and she was there to assail the public with unstifled Self. The New York Times allowed that she had a “genuine talent” and an “uncanny gift.” It was a small nod of legitimation to the power of her highly erotic terror grotesquery. When Divine died in 1988, it was a decidedly uncamp end for the explosive chimera of vilified and devalued sexuality the former Harris Glenn Milstead had come to embody. Right before she was scheduled to appear on the sitcom Married with Children, her heart blew up inside her chest, vaulting Divine into oblivion.

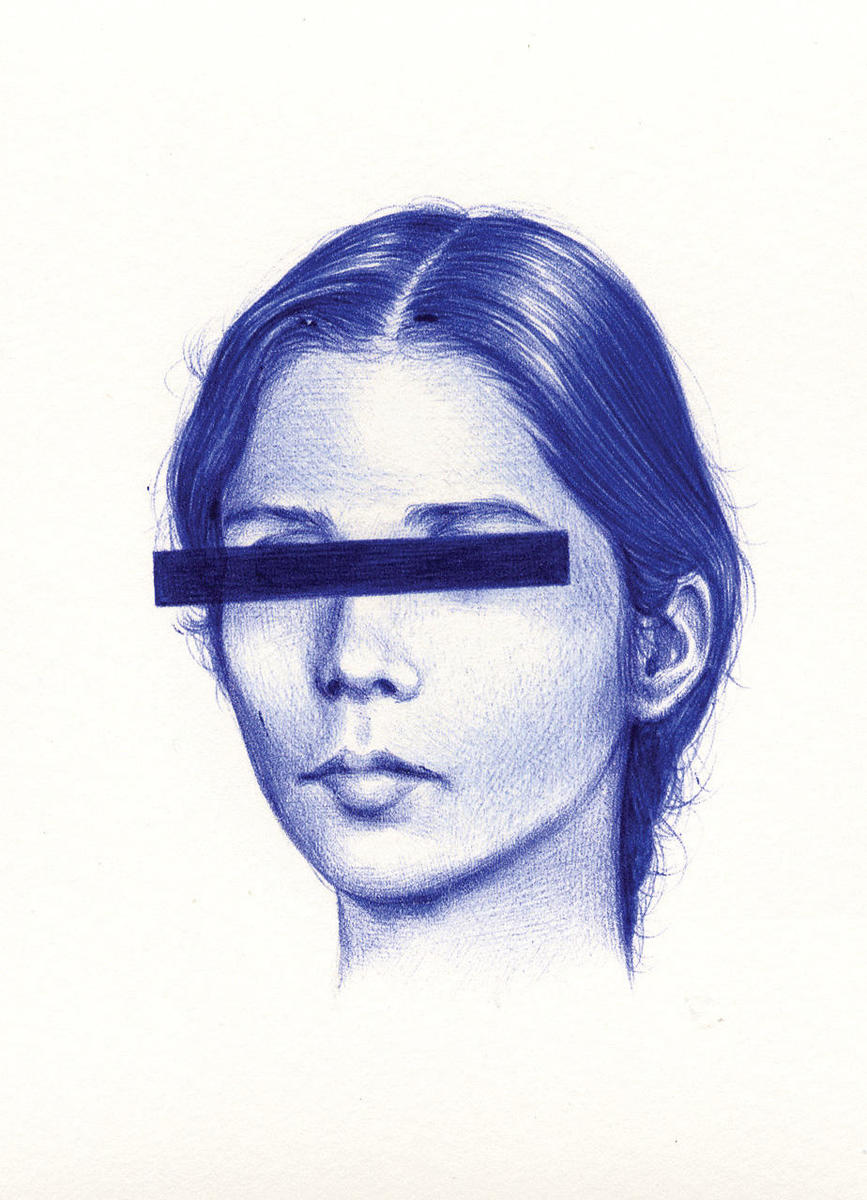

In a 1992 interview, John Waters drifted from the subject of his lost muse Divine to the person of Dhanu, the assassin who had killed Rajiv Gandhi in a suicide bombing the year before. Waters invoked the image of Dhanu kneeling at the feet of Rajiv Gandhi before she carried out her suicide attack. In a photograph taken before the explosion, white bows bloom at the roots of her braids; underneath her clothing she was wearing a denim vest laden with heavy steel pellets and nitroamine. She was photographed in mid-rapture, emoting the “internal sense of satisfaction,” of completion, that Audre Lorde described as the goal of all erotic experience. It came as little surprise that Waters would be enthralled with the “look of bliss” on Dhanu’s face right before she detonated herself.

“To me there’s something very appealing about that. I couldn’t imagine doing what she did, but that’s why I’m fascinated by it. If I could understand, I wouldn’t be interested.” Like porn or snuff, Dhanu’s photo exerts a morbid magnetic pull that stirs the “measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.” Printed, ogled, and censored, photographs of this temporal moment of “erotic actuality” refract and distort in the wake of woman-wrought carnage. Images of female suicide bombers resonate with the public in ways that bearded or masked males never do. Young women are the noblest martyrs and the most dangerous threats.

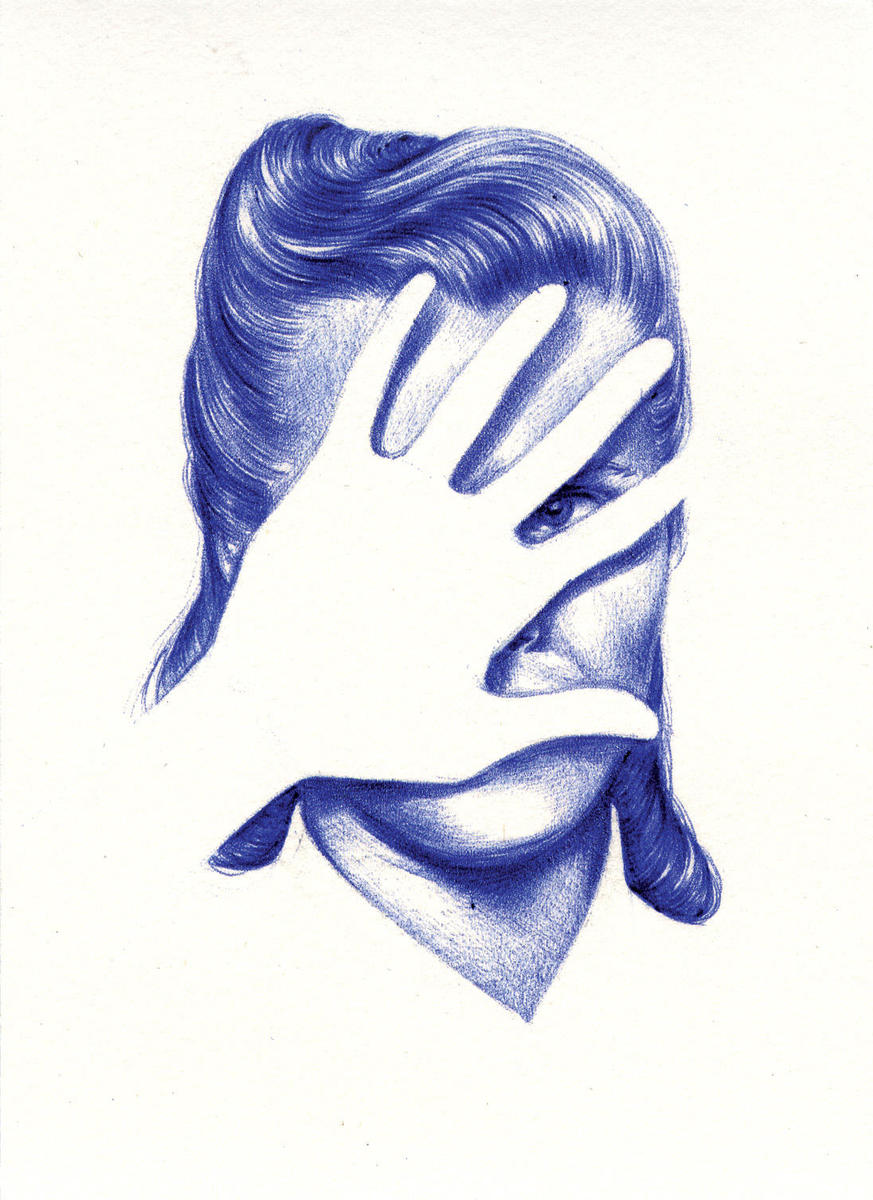

When women openly display the erotic (and I don’t mean lift their skirts and spread-eagle), be it expressed in sexual desires, spiritual aspirations, or political agendas, it can cause a frenzy in those who witness it. Instinct instructs the fearful and weak to stop her from coming into that power, to sequester the menstruating, hide the beautiful, and lock up the insane. But it is precisely these maligned women, wiser and empowered for having dwelled in obscured and darkened places, who are dangerous.

Dhanu’s story is shrouded in mystery; even her date of birth remains unconfirmed. Allegations by journalists that she was propelled toward suicide-terrorism by a childhood sexual assault have been denied by the Indian authorities. But perhaps her motives are best kept muddled. More defiant than enraged, more righteous than religious, more strategically powerful than a legion of men, the female suicide bomber creates a vortex of fascination. She may never get her seventy virgins, but she gains a world of reluctant admirers.

It’s dangerous to be a woman so empowered. Irma Grese was one of the legendary she-devils of the Nazi regime. Dubbed the “beautiful beast” by her prisoners at Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz, she was accused at her trial of sadistic torture, murder, and sexual excess during her time as guard in various women’s camps. In photographs both before and during her trial at Lüneburg, Irma exudes an intensity and wide-eyed derangement akin to Charles Manson, combined with the unapologetic conviction and fervor of one of his “family.” She was both monster and maiden under prosecution. The arguments of the British prosecutor, one Colonel Backhouse, hinged on Irma Grese’s choice of attire and weapon within the camp.

He coaxed her in a patronizing sexual tone, asking if she liked having a revolver strapped to her waist or if she enjoyed wearing heavy boots. She matched his perverse prodding with shameless admission:

Backhouse: You thought it very clever to have a whip made in the factory, and even when the Kommandant told you to stop using it, you went on, did you not?

Irma: Yes.

Backhouse: What was this whip really made of?

Irma: Cellophane paper plaited like a pigtail. It was translucent like white glass.

Backhouse: It was just your bright idea?

Irma: Yes.

Irma knew exactly what she was doing.

Grese went to the gallows in 1945, along with a slew of male SS officers and only two other women. She had admitted to agency and awareness, and she wore it on her face. According to witnesses, it was apparent in her demeanor that she had taken personal pleasure from breaking bones and wielding her see-through whip. On the day of her execution, Irma Grese stepped to the chalk mark on the trapdoor and refused a hood. Her neck did not snap. She hung for twenty minutes before the doctor cut her down.

Much of the controversy around Irma Grese’s guilt springs from issues of conscious decision and agency. Although it is clear from her testimony that she was well versed in everything going on in the factories and camps, her supporters (and there are many) cling to images of her lovely face and refuse to believe such a beauty could choose to become such a beast.

In 2004, photojournalist Rita Leistner captured on film the female patients of Baghdad’s Al Rashad Psychiatric Hospital. They formed a motley crew of battered wives, murderesses, nymphomaniacs, and handicapped. In her pictures they prowl unsterile daiquiri-colored hallways, smoke, and bite their nails behind makeshift hospital curtains made of patterned sheets. Their heads are shaved, teeth missing or broken, cheeks sticky with tears and snot. But Leistner captured a boundless beauty in her subjects. They are strange, disturbing, aesthetically arousing.

Four years later, the replacement director of Al Rashad, one Dr Sahi Aboub, was arrested by American troops. The hospital was raided for medical records and clues to a sinister plot. On February 1, two mentally ill women from Al Rashad had been passed to Al Qaeda. Sold into terrorism and outfitted with crude explosives, they were sent into a crowded pet market and detonated by remote control.

It was a baffling attack for Baghdad, one that elicited shock from a city plunged so deep in horror that only the most despicable acts still had the power to outrage. Eyewitnesses described the mangled confusion of human and animal corpses. The dust and blood and bones of Al Qaeda’s unwitting martyrs smoldered on the streets, as the cowards with the triggers got away. Su Ling made one last fleeting appearance on celluloid, a ten- minute rumble called Catfight in Mini Skirts, in which she and a blonde named Angie wrestle on a mangy orange carpet. The blonde swings her head back and forth to violent effect as she pretends to choke her opponent. This superfluous thrashing gives Su Ling her opportunity: she flips the blonde onto her belly, and after a few genuine smacks and hog-tie crunches, Angie turns to rubber. Her limbs flap pointlessly. Without resistance, any hint of eroticism is sapped right out of the fight, but the elastic of Su Ling’s garters hold tight and her ferocious strength is apparent as she squats on Angie’s back and arranges her into a backwards pretzel. Angie plays KO facedown, and Su Ling places a stacked heel on her vanquished ass. The camera zooms in on Su Ling’s mouth, an expressionless oval, closed. She’s dead-serious about winning. Like the hyper-focused faces of girl bombers and monster maidens, Su Ling’s is determined, bold, and a little berserk. This fight was beneath her; she stooped to conquer. The film immolates in a greenish fizz, and Su Ling is gone without a trace, her whereabouts as of this writing still unknown.