London

Word Into Art: Artists of the Modern Middle East

The British Museum

May 18–September 3, 2006

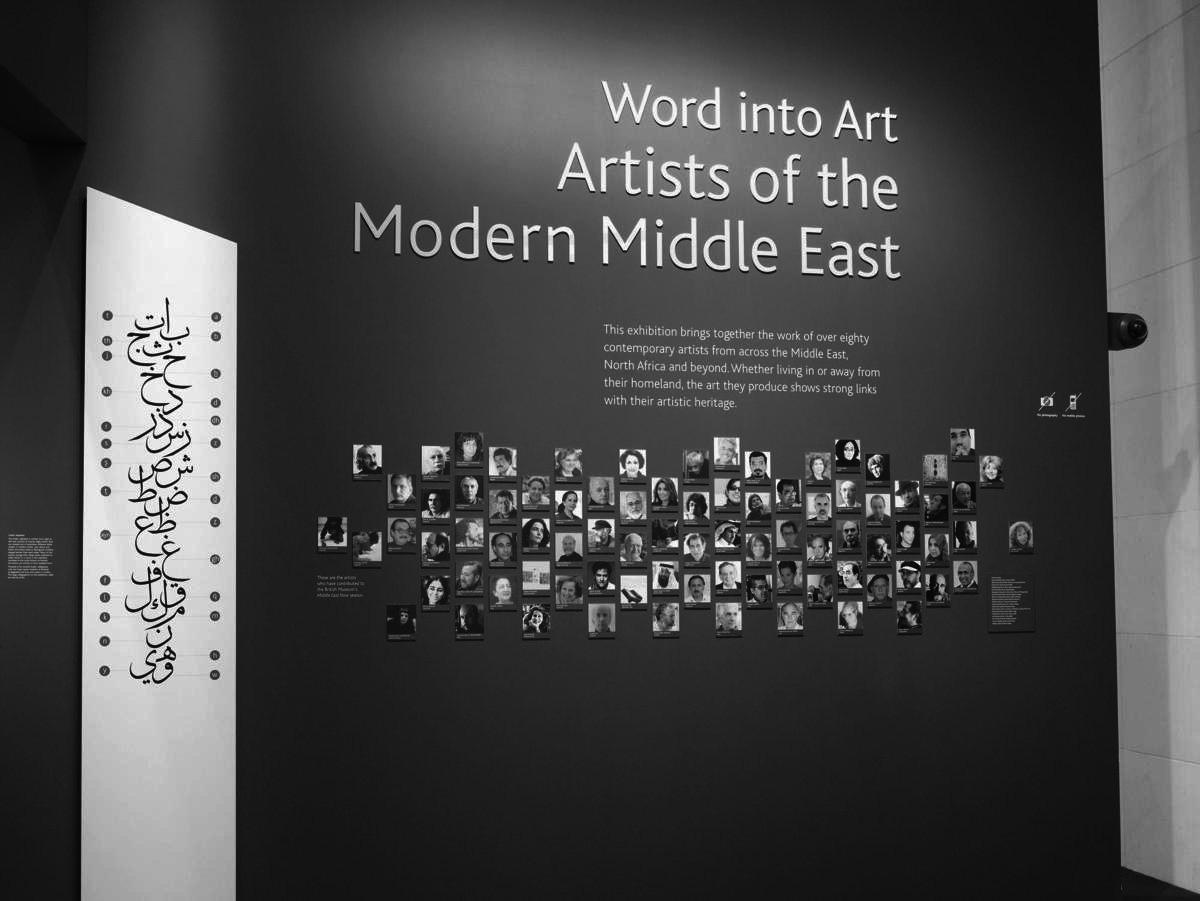

“This exhibition brings together the works of over eighty contemporary artists from the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. Whether living in or away from their homeland, the art they produce shows strong links with their artistic heritage.” So we are informed by the wall text at the entrance of the Word into Art exhibition (subtitled “Artists of the Modern Middle East”) recently on show at the British Museum. Underneath the text, photographs of the participating artists were placed in rows, with their printed names neatly identifying them.

The (if one is to be kind) misguided curatorial decision to introduce the exhibition in this format underlines the problematic nature of the endeavor. Grand and general statements are made about both art and artists (culprits pinned to the wall, members of some tribe deciphered for us through the lens of anthropology), a specific unified and fixed artistic heritage is presumed, and maybe most problematic is the absolute assurance that what they produce (not as individuals, but as representatives of the Modern Middle East of the title) is strongly linked to that heritage. For the Middle East, the argument goes, will always remain in thrall of an imagined tradition, by a past that gloriously recedes, static and fixed, while the cultures of other regions become the harbingers of modernity and development.

We are informed that most of the works are from the collection of the museum, whose policy since the mid-80s has been to collect modern art from the region — as long as it possesses a textual element, and therefore may be tied into their collection of (admittedly fine) Islamic calligraphy. Other than the obvious lack of sophistication of such a curatorial approach, its passive acceptance of a Victorian model of linear history, of cause and effect, of essential identities, and the apparent confusion between art as a self conscious conceptual and intellectual practice and art as an essentially decorative skill, it is also a model that denies its subject—in this case modern art from the Middle East — the possibility of functioning within different (more generous, less restrictive) genealogies. It thus places severe restrictions and limitations on itself as a collection, while laying totalizing claims to the corpus of work that it possesses. This is obviously an approach that excludes a tremendous amount of the most interesting and dynamic work being produced at the moment. Such fallacies are typical of an arrogance whose sole redeeming factor might be that it is blind.

This is a highly condescending exhibition, where artists’ works (regardless of formal quality or conceptual underpinnings) are used to demonstrate a specific thesis about the region. The dominant metaphor at work here is that of “possession” — a collection of glamorized artifacts whose function (symbolic value) is to normalize and validate specific ideological (dare we say racial?) agendas; the “Middle East” is an essentially unmodern place, its relation to modernity derivative of western influence and only accessible through some kind of reaffirmation of a basic predetermined identity. The exhibition’s linear progression through four numbered sections — Sacred Script; Literature and Art; Deconstructing the Word; and History, Politics and Identity — clearly resonates with the essentialist implications that seem to prefigure the exhibition itself.

Other than the inane nature of such generalities, these are headings that give us, the viewers, easy access to what must seem to be traits of a specific cultural landscape. This approach leans heavily on a classical anthropological model, where the works become examples of a cultural landscape, alienated from the viewing experience, a foreign Other to the art object, trophies from faraway cultures. The progression from the sacred to history and identity inextricably links these concepts to a chain of causality that frames our viewing experience. The works on display are supposed to reflect some essentialized truth about that culture. Last but not least, it is important to point out that the title of the exhibition makes one more totalizing reduction: that this is an essentially and historically artless place (that old cliché: Middle Eastern cultures have to discover art by transforming their mainly literary heritage through an interaction with western culture). All aforementioned points are underlined and enhanced by the plethora of Qur’anic verses, Arabic sayings, and lines of poetry (translated into English and calligraphically rendered on the walls) that punctuate the exhibition.

It thus comes as no surprise that this is an exhibition that succeeds in bringing together all the worst traits of the state-sanctioned, mainstream decorative art produced in the region. Ironically enough it is the region’s nationalist, state-sponsored productions that most neatly fit within the British Museum’s perspective. Abstract calligraphic doodles and (the ever present) Sufi references are surrounded by megalomaniac colorful sculptures that would fit quite nicely in the gardens of the Creativity Center in Cairo. Faux naïve village scenes and Bedouin happenings are framed by the more tasteful pop-orientale of Chant Avedissian’s glamorized nostalgic wallpaper, as well as the decorative melancholic, which seems to be dominated by Iranians like Shadi Ghadirian, Bahman Jalali, and Malekeh Nayiny. Although the stalwarts of the modernist scene (of different trends and countries) in the region are present—such as Rachid Koraichi, Mohamed Abla, Youssef Abdelke, Shafic Abboud — the exhibition also attempts to cross ethnic and regional boundaries by a few representatives of non-Muslim culture: the Japanese Kouichi Foaud Honda and the (unproblematized) Israeli Michal Rovner. These additions, however, are not enough to render inclusiveness more than illusory, or token. Including works on the basis that they include text brings together a number of anomalies that remain unexplained. Youssef Nabil’s trendy narcissistic photograph, for example, was more fitting for a glossy lifestyle magazine.

The museum here (much like a neo-con think tank relying on local consultants) makes arguments of cultural superiority, which are implicit and unspoken, all the more salient. Most disturbing was to watch this act of validation at work in relation to Muslim and Arab visitors, who, on both my visits, seemed to passively consume the museum’s position. The works on show became ciphers of their own identity, and a positive sense of ownership (easily translatable to a sense of a specific essential identity) was communicated in some of the conversations I had with different visitors. It seems that the shadow of the institution strikes deep, and I was left with the unsettling thought that what is being subtly confirmed, affirmed and maintained is one specific image.