A vanload of city kids takes the wrong turn in the wrong jungle. Witchcraft ensues. Of course, they pass a river polluted by industrial waste. Of course, there is a tribe of cannibalistic zombies who live on its banks, who take a culinary interest in one of our city slickers. And of course, there is a serial killer in a burqa who greets the rest of them with a whirling, spike-studded flail. And there’s a midget. This, in brief, is Zibahkhana, Pakistan’s first high-definition video film, and the brain-hungry lovechild (or love- hungry brainchild?) of Omar Ali Khan, a forty-five-year-old first-time director and schlock-horror cineaste whose kingdom was built on ice cream.

Omar began his tour d’horreur as the black sheep of a prominent Pakistani family. He was not conventionally ambitious. He went to college in America and graduate school in England, but couldn’t bring himself to become an academic. Upon returning to Pakistan, he failed the civil service exam (to the amusement of his father, a diplomat) and took a job teaching high school, which he did for almost ten years, though he found it boring. Mostly he did what he loved — he watched movies. All kinds, from mainstream Bollywood epics to obscure second- and third-tier Hollywood films to the indigenous outpourings of Lollywood, Pakistan’s own film industry. And he ate ice cream.

He ate a lot of ice cream. Having gone to college in Boston in the 1980s, the golden age of the independent ice cream store, he had acquired a taste for natural flavors and organic ingredients, as well as admiration for the “smoosh-in” (the original ice-cream-and-candy-bar hybrid). But the ice cream back home was brightly colored, generic, and tasteless. Worse, the ice cream shops in Islamabad were aimed squarely at children, complete with Mickey Mouse murals. One day Omar decided to try his hand at making ice cream for himself. When the results were encouraging, he thought about selling it to others, and in August 1995 he and his younger brother Ali opened a makeshift business out of their parents’ Islamabad home. It would not be safe for children. They called it the Hotspot.

Omar and Ali’s ice cream was gourmet — no artificial coloring, no preservatives or additives. Instead of plastic buckets, they used wooden tubs. All the ingredients were fresh: August is mango season, so that became one of the first flavors. Scraping imported beans from Madagascar and soaking them overnight in cream lent their vanilla its exquisite richness. (They weren’t wholly virtuous: they also featured Malted Chocolate Chip Cookie Dough.) Despite their odd location, the lack of seating, and a limited range of flavors, customers showed up in droves. One year later, when a restaurant in the shape of a railway coach at Gol Market closed down, the Khans gleefully relocated.

In Islamabad there was not much by way of cafe culture, no teenage hangouts as such, and young people flocked to the Hotspot. The space itself was decorated like the inside of Omar’s head. Lurid movie posters lined the walls; assorted horror props hung from the ceiling. The soundtrack was a careful mix of period funk, nightclub numbers from swinging Lahore, Bombay disco from the 1980s, and the occasional Blondie track. Thus emboldened, Omar and Ali started publishing the Scream, a newsletter about ice cream and movies that would grow into a full-fledged fanzine devoted to “Horror and Cult, Trash and Z-Grade” cinema. Improbably enough, the formula was a success. Today there are five Hotspots, including a flagship store with an expanded menu of organic dishes and a bookshop at Gaddafi Stadium in Lahore, where the country’s major international cricket matches are played.

That Pakistan’s most distinctive cafe chain and South Asia’s most discerning horror movie resource should have sprung from ostensibly serene Islamabad makes a perverse kind of sense. A young city of under a million people, it was created in the 1960s by Pakistan’s first military leader, Field Marshall Ayub Khan. It is unrelentingly rich and unrelentingly clean. Traffic flows demurely, gigantic homes are tucked inside high compound walls, and the effect is an eerie stillness. There is no street life to escape to, no crowd within which to get lost. There are few public spaces, save the shopping mall. Islamabad’s elite tends to do as it pleases (behind locked doors), and despite fluctuating undercurrents of class resentment and moral fervor, the arrangement is usually acceptable to all. Sometimes, however, it is not. The occasion for the bloody siege at the Lal Masjid in 2007 was a vigilante raid on a well- known brothel by female students from the mosque. Still, if there is a prevailing mood in Islamabad, it is one of listlessness. In a city of such peculiar calm, it seems appropriate that a horror-themed ice cream parlor should be the center of social life.

I did not come to Pakistan for the ice cream. Nor was I primarily interested in talking about Zibahkhana — I hadn’t managed to see it yet. My first interest was in the Hotspot Online, the website Omar Khan launched in 2000 as an archive and extension of the best of the Scream. By now there are hundreds of thousands of words on thousands of movies — Hollywood, Bollywood, Lollywood, and then some— as well as film clips, hand- painted copies of movie posters for sale, travel writing, a “rough guide to Islamabad,” and incredibly weird blog posts (most recently, a contest gauging the dictatorial prowess of Pervez Musharraf as compared to Idi Amin). It was at the prompting of the Hotspot Online, for instance, that I was encouraged to seek out the 1990 Punjabi-language hit International Gorillay. Its principal character is a criminal mastermind named Salman Rushdie, who sets out to destroy Islam by luring Pakistanis into gambling, dancing, and all manner of sundry sins. Rushdie tortures his prisoners by reading to them aloud from The Satanic Verses; the brave mujahids out to stop him are disguised in Batsuits; and in the end, a quartet of levitating Qur’ans shoot laser beams into Rushdie’s head, causing him to explode.

Omar’s site had already acquired an international cult following by the time I heard about it, but I was suspicious. I had spent a futile year trying to write about two Indians actors, Govinda and Mithun, who together had starred in the majority of the most outlandish Bollywood offerings since the late 1970s. The problem was getting the tone right; I couldn’t find a template. I read books on film theory and found them useful, but professional theorists seemed not to allow for the possibility that one might actually enjoy watching the thing one is theorizing. And yet enjoyment was not without its hazards; so much middle-class appreciation of “low” culture amounts to intellectual slumming, and I knew too many snobs in Soho and Shoreditch and Bangalore who enjoyed bad cinema badly. But it turned out that Omar’s criticism was visceral, sincere, and sharp; loving yet caustic, like the work of a film theorist on truth serum and crack at the same time. I had found my model. I kept browsing, and found Omar’s own extensive writings on my putative subjects. I quietly shelved the project.

You can lose yourself in the forest of text and image that is the Hotspot Online (and not only because the site map is incredibly confusing). Reading Omar’s reviews scrambled my mental geography; his Pakistan is a land of mayhem, whimsy, and all-encompassing strangeness. Places that only existed for me through newspaper accounts of Taliban strongholds were repopulated with lecherous beast-ladies hell-bent on plunder.

Omar’s predilections notwithstanding, the majority of Pakistani films are not particularly subversive or strange. And the actual history of Lahore’s film industry (the “L” in Lollywood) predates Pakistan. The city’s first films were made in the 1930s and played to a wide subcontinental audience. In fact, colonial India’s first film with sound, Alam Ara (The Light of the World), was made there in 1931, inaugurating a musical genre that continues to this day.

Lollywood and Bollywood both flourished in the decades after partition. On the Pakistani side, the industry was given a boost in 1965, when the longstanding ban on Indian films was suddenly enforced after armed conflict in Kashmir. Lahore was producing a record number of films in a wide variety of genres, including one brief but crucial foray into horror. Zinda Laash (The Living Corpse) was a brooding 1967 black and white thriller starring an up-and-coming actor named Rehan as Professor Tabani, a sort of Dr Jekyll and Mr Dracula. Zinda Laash made Lollywood film history twice — the first horror film, and the first and only film to earn the label “For Adults Only,” after the board of censors accused the film of being “corruptive and evil.”

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s Prime Minister during this “golden age,” is sometimes credited with creating an open climate for cultural expressions. In retrospect, however, his 1977 decision to ban the sale of alcohol (perhaps a last-ditch effort to appease conservatives) was the beginning of the end of the era. Bhutto was promptly overthrown by General Zia-ul-Haq; two years later, after consolidating power (and executing Bhutto), Zia moved to enforce the ban. Out went the bars and nightclubs where alcohol had been served — and with them, the paradigmatic Lollywood “nightclub number.” More significant, if less dramatic, was the widespread introduction of VCRs, which allowed increasing numbers of Pakistani film viewers to circumvent the Bollywood ban in the privacy of their own homes. (The Urdu language spoken in most song-and-dance Lollywood films is the same language as that spoken in Bollywood films, and the “family melodrama” has been the dominant mode in both Lahore and Bombay.) By the early 1990s, there were those who believed that the industry might never recover.

The decline did not affect all segments of the film industry equally, however, as Hotspot aficionados can attest. A number of epochal Punjabi films, and even a few in Urdu, still managed to get made in the late 70s and 80s, while cinema in Pushto, the language of Pakistan’s oft-lawless northwest corridor, went completely berserk.

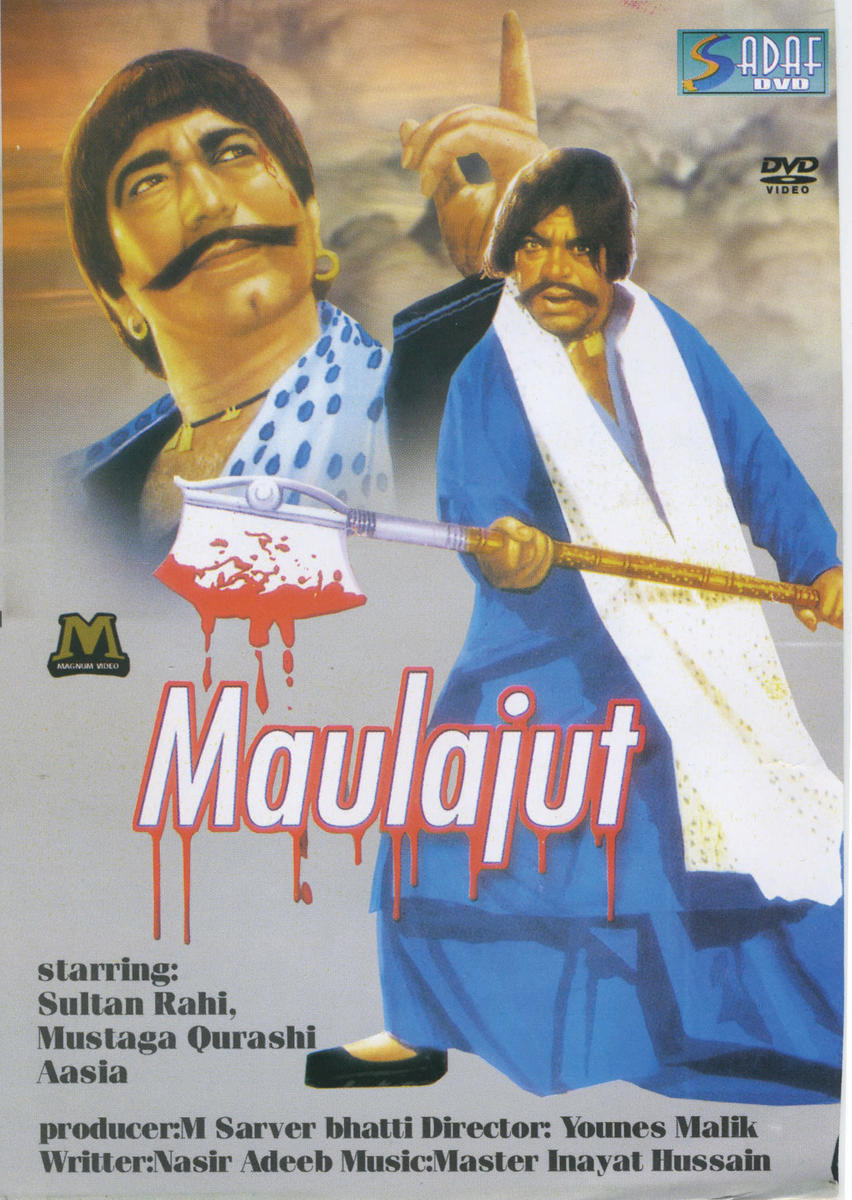

Consider Aurat Raj (The Reign of Women), a rare and rarefied Urdu classic. In 1979, the bodybuilder, singer, and actor Rangeela added another line to his resume: director. His film had a beguiling premise. A group of women discover a bomb that switches gender roles and seize power by setting it off. In this brave new world, women wield machine guns and flick their cigarettes with an easy flair, while the men twirl in slow motion and swing their hips coquettishly. “I used to be Sultan Rahi,” simpers one of the ex-men, after he is saved from molestation at the hands of a vengeful band of marauding women. There’s not a trace of camp in the scene. And it’s a beautiful moment because he really is Sultan Rahi, the actor best known as the ax-wielding macho man Maula Jat, an archetypal Punjabi folk hero whose eponymous vehicle was also released that year.

But where Aurat Raj came and went, Maula Jat was a genuine blockbuster — a gory tale set against a backdrop of feudal injustice and told in a continuous high-pitched scream. It didn’t invent the character — Sultan Rahi’s first time out as the hearty peasant with arms of steel and a heart of gold was in Wehshi Jat, four years earlier. And it almost didn’t happen at all — Maula Jat’s anti-establishment ethos caught the attention of General Zia, and it missed being banned by a whisker. Maula Jat became one of the highest grossing films in Pakistani history, transforming Sultan Rahi into a superstar and spawning a slew of unofficial sequels that are still being made. The plot of the film is simple or complicated, depending on how you look at it. Suffice to say that it involves our rustic vigilante, some bloodily detached body parts, and an exacting feudal villainess who shoots her brother through the heart for failing to adequately rape the village belle.

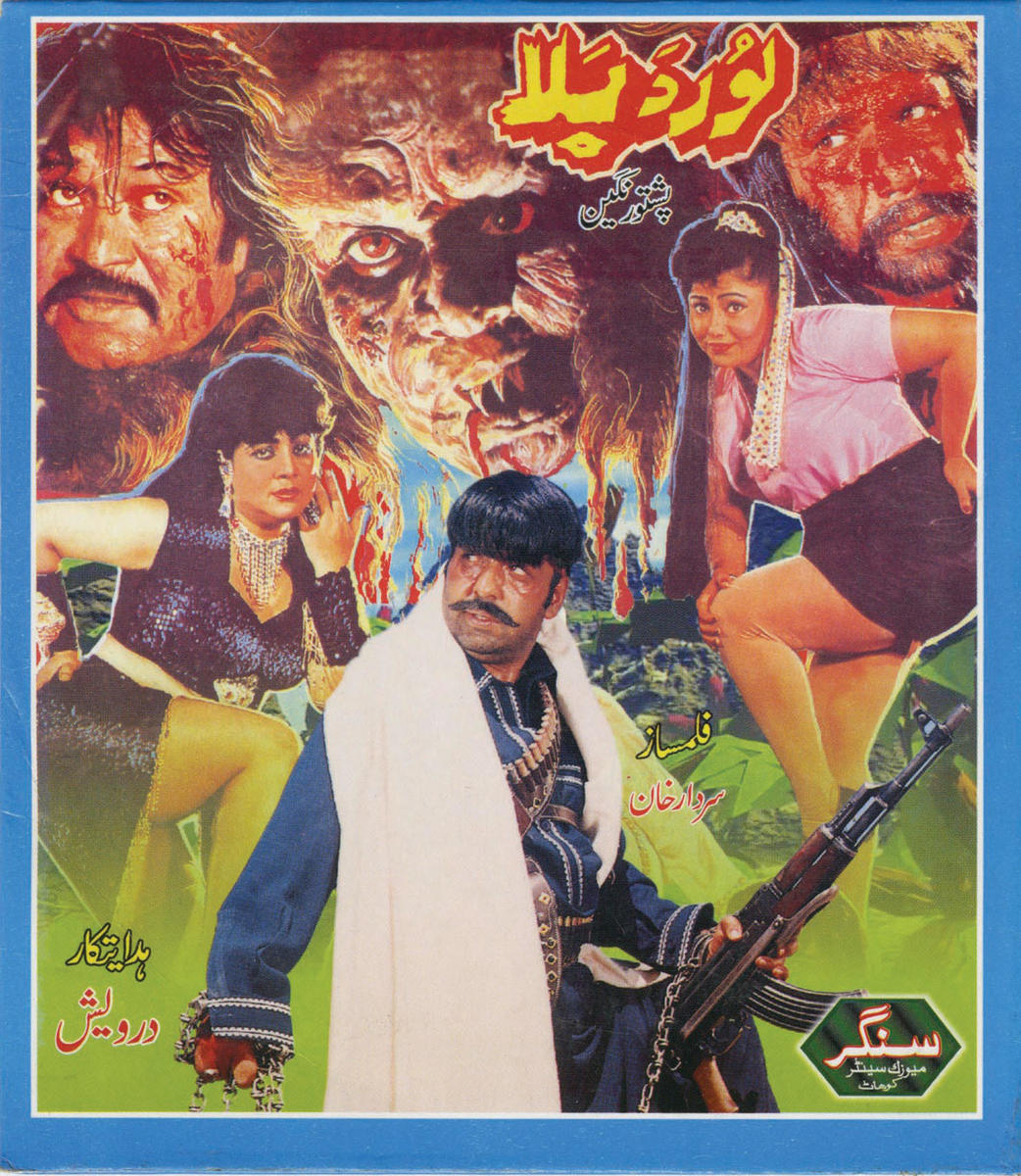

Tales of feudal injustice are not uncommon in Bollywood, either. But the most distinctive of Pakistan’s film industries, Pushto cinema, is unlike anything else. In Pakistan today, it is a byword for porn (or “fully-clothed porn,” as Omar would put it). And its titillations are nearly completely unpredictable; recent films have involved floating phalluses, lascivious hairy she-beasts, all-cavewoman catfights, even the odd amorous grizzly bear. Its leading ladies are, almost to a lady, incredibly fat. Perhaps Lour Da Balaa (Daughter of the Beast), a 1999 film featuring a female monster given to brutally raping soldiers and a woman who fellates a pistol, is perfectly sensible to audiences on the outer fringes of Peshawar; as for me, it rearranged my molecules. Naturally, Omar gives it loving attention on the Hotspot Online.

I ended up spending several days in Lahore. In the daytime I met with Omar and toured both Hotspot locations. It was at night, however, that I truly saw the sights. I can confirm that for all its manicured suburbs and ancient monuments, and even without nightclubs, Lahore remains a hotspot for sin and sinners.

I discovered this mostly thanks to Mohsin Raza, aka Sattar Masihi, one of the last of a dying breed of billboard painters. For decades, movies had been advertised by lavishly detailed billboards. But in the new millennium, with the advent of digital printing technology, this art form has almost disappeared. Producers and theater owners prefer digital prints, which are cheaper, faster, and more realistic. Artists like Mohsin face either unemployment or a future of painting shop signs. Inevitably, Omar Khan is a fanatical lover of the artisanal craft of billboard painting, and tucked away in a corner of the Hotspot Online, you will find scores of two-by-three-foot movie posters for sale, hand-painted by Mohsin and his ilk. Omar first met Mohsin several years ago at Royal Park, Lahore’s legendary movie studio, and recently curated an exhibition of his work in London.

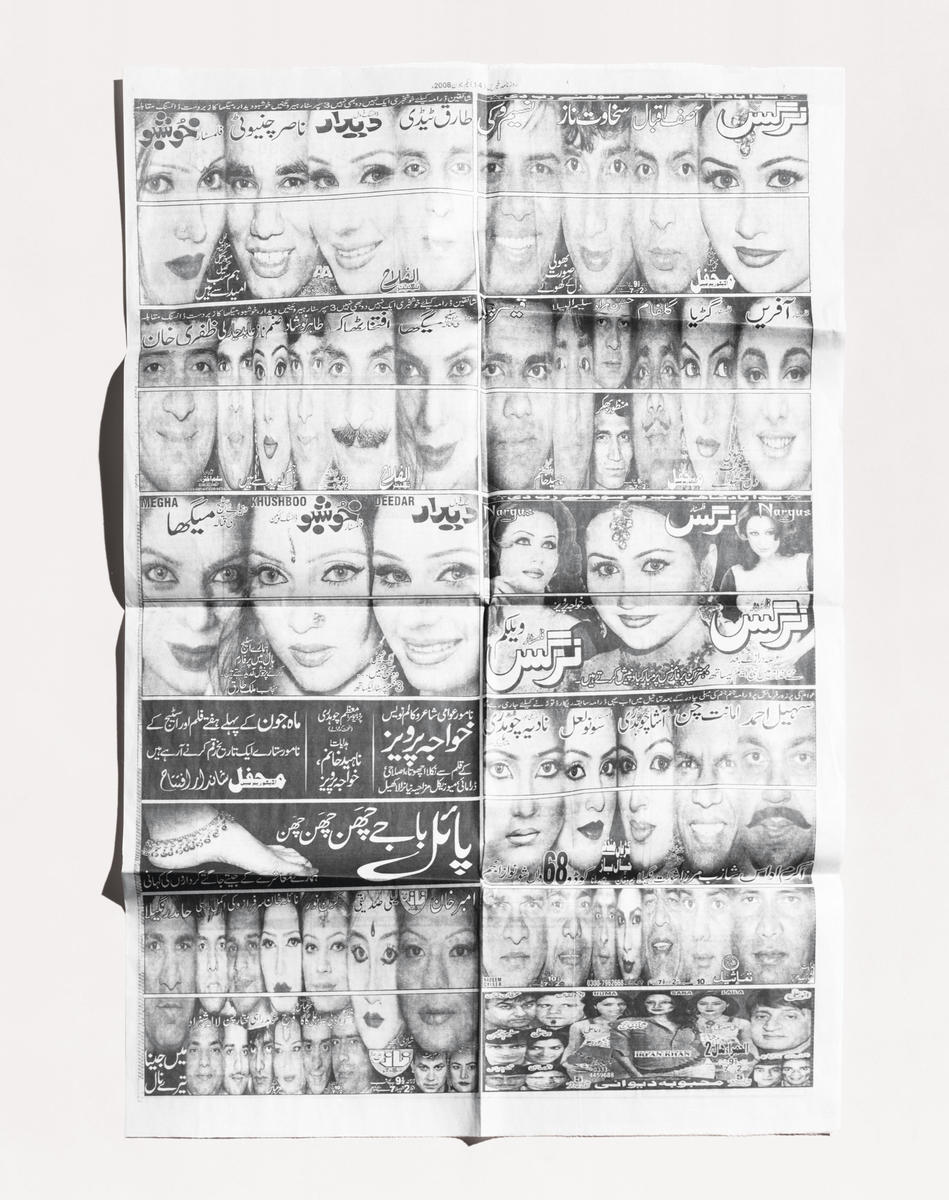

Mohsin loves theater. Every night in Lahore at ten o’clock, the curtain rises on a series of live tableaux, enacted with song and dance by female performers. The most famous, like Madam Nargis, are superstars whose recordings sell internationally; newcomers, meanwhile, usually resort to wardrobe malfunctions to pull in the crowds. Regardless of the stature of the performer, almost every theater is booked out every single night, at a cost upwards of 2000 rupees per (male) head. Live theater here is not exactly a secret. It is heavily advertised on the street and prominently featured on Fridays and Sundays in Pakistan’s highest-circulating Urdu newspaper, the Daily Jang. But its public nature is no indication of its respectability, and the clearest sign that it might be frowned upon is a recent film from one Rasheed Dogar entitled Sachaday Night. I had earlier squirmed through another of Dogar’s creations, Murdar (by which I think he meant “murder”), so I was acquainted with his oeuvre. It is rich in “impact shots” — a favorite technique of Indian soap operas too — where the camera zooms in on a particular scene and jerks up and down and sideways, as if caught in an emotional earthquake. The protagonist spends his Saturday nights preying on live theater actresses (who are, of course, all prostitutes). On the pretense of a quick romp, he takes them home, kills them, and has his father hide the bodies in his backyard. Eventually the police track him down and lock him up. Upon further reflection, the policemen realize that he’s been performing a valuable service by eliminating vice and temptation, and, in the best interests of society, they let him go.

When asked to account for his love of film — and his taste for trash — Omar, in a time-honored maneuver, blames his parents. His father is a Hitchcock obsessive; his mother’s family, devotees of the tear-jerkingest Lollywood melodrama. But the primal scene of his childhood, his initiation ritual, if you will, transpired during a full moon in Kent, England, where the five-year-old Omar and his parents attended a nighttime showing of The Wizard of Oz. “I was dragged out of the cinema in a state of total hysteria,” he says. “Traumatized into a state of unsurpassed fear, and loving every second of the sensation.” Like many children, Omar had a favorite character. Unlike many children, his favorite was the Wicked Witch of the West. And unlike nearly everyone, the character Omar identifies with (or at least, most closely resembles) is not plucky Dorothy Gale or the Cowardly Lion but the man behind the curtain, the great Oz himself.

Omar is a highly hands-on manager, meddling daily with one or another aspect of his businesses, up to and including the songs on the jukebox at the various cafes. But he prefers to be hands-on behind the scenes. He is strikingly introverted, preferring not to leave home if he can help it. He spends most days in cotton pajamas, working out of his house in Islamabad, near but not within the fabled “posh sectors.” (A newspaper report of a recent attempt at bombing the Danish Embassy took care to mention that it had happened in “F-6/2 posh sector”). His living area is dark and furnished with a variety of state-of-the-art electronics, including a professional projector that beams onto a giant collapsible screen. The whole house is a sort of deluxe version of the Hotspot idea. There is a bookshelf filled with biographies of serial killers and a desk with a computer jacked into what must be one of the best internet connections in Pakistan. Original movie posters line the walls, including the Gunmaster G-9 classic Surakkshaa, the pioneering Wehshi Jatt, and Saw, a Hollywood film that Omar doesn’t like but wistfully admires for having initiated a genre called “torture porn.” Food is usually ordered out from the Hotspot, though his custom does not usually include ice cream. Omar has all but lost his passion for it — and if photographs of him circa 1995 are any indicator, he’s lost a lot of weight as well. On the outside, his house is plain, worn, and somewhat unadorned. In Bangalore, where I live, this would be another ordinary upper-class dwelling; in status-conscious Islamabad, it looks positively mysterious.

This summer, all of Pakistan was thrown into a cycle of power outages, causing untold damage to his filmic explorations. Omar was sanguine about it, and it seemed as though he relished the idea of conversation as a kind of novelty. But he remains the kind of person who luxuriates in his privacy. He was at his most animated discussing, say, the minutiae of the life and death of Silk Smitha, South India’s greatest vamp, or when talking about music.

During one our evenings together he recorded his radio show, “Mondo Bizarro,” which broadcasts nationwide on CityFM. The previous week he had announced a quest for the world’s worst song. “Really awful stuff,” he said, proudly. “The most unlistenable songs ever.” There were a number of contenders. Bappi Lahiri’s “You Are My Chicken Fry” from the film Rock Dancer seemed like a possibility, though Omar is a huge Bappi fan generally. Anu Malik’s “You Look to Me a Virgin,” from his English album entitled Eyes, was near the top of the list. Then Omar heard “Desire” from Deepak Chopra and Demi Moore — a florid Sufi poem set to a Buddhist beat — and he knew he had a winner. Later on in the broadcast, he relented a bit. “I think I’ll just play some Sylvester and tell people they’ve got to live a little, you know?”

To live a little, or indeed at all, is not a choice available to most of the characters in Zibahkhana. The story of the film is every bit as serendipitous as Omar’s career itself. In early 2001, he was contacted by Pete Tombs and Andy Starke, a British duo who had discovered the Hotspot Online. Pete was a London-based writer and author of two cult books: Immoral Tales, on the erotic horror films of Europe, and Mondo Macabro, a global survey of “fantastic cinema.” The British duo were preparing a television series based on Mondo Macabro for Channel 4; they also planned to launch a DVD label devoted to recirculating lost genre classics. It was a meeting of like minds, and the beginning of a series of collaborations. Omar appeared as a “talking head” on the South Asian episode of Mondo Macabro TV; shortly thereafter, a joint Mondo Macabro/Bubonic Films edition of Zinda Laash was released under its English title, The Living Corpse, with plans (as yet unrealized) for an edition of Aurat Raj.

When Omar decided to make his own movie, Pete and Andy were the first people he talked to. They decided to produce the film together, Pete assisting Omar in the writing and Andy taking charge of the editing. Omar would direct. The script was a tribute-laden horror film set in modern day Pakistan, an “ode to the masked slasher” from trash-splatter landmarks like Halloween and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Their first attempt at production was derailed by the Kashmir earthquake of 2005, in which close to eighty thousand people died. The shoot finally began on July 10, 2006 — just in time for the monsoon. Start to finish, it took one month, during which time the Islamabad police found two dead bodies in the forest where the film was being shot. (It turned out that their chosen forest was a choice dumping ground for inconvenient bodies.) A few scenes were reshot in November, the post-production was insanely rushed, and in March 2007, Zibahkhana made its world premiere at Denmark’s national film festival.

Zibahkhana is a supremely satisfying romp. The Burqaman — definitely the world’s first burqa-clad serial killer — is an instant icon. Omar admits that the idea derived from a childhood fear of the burqa, “a fantastically gothic and dramatic outfit that manages to strip all expression, emotion, and warmth from a human face.” He is both perplexed and delighted that it didn’t cause more controversy. But the Burqaman is just the beginning. The film is studded with tributes and in-jokes for the cognoscenti (which is to say, readers of the Hotspot Online). While the film’s teenagers are a mix of up-and-coming actors and absolute beginners, most of the other characters are played by legendary but forgotten or underrated actors. Rehan, the vampire-scientist from Zinda Laash, has a pivotal role; the late Najma Malik, famous for playing a maniacal witch in the television serial Ainakwala Djinn, plays the Burqaman’s maniacal mother. The soundtrack consists of sizzling, scratchy tunes from old Lollywood dance sequences.

And though Omar bristles at the idea that his film is some kind of political statement, his characters do tend to be rather heavily oppressed: the hijra, the single mother, the abandoned poor, the miserable Christian, the misunderstood Faqir, and the mama’s boy who was raised like a girl. None of them are straightforwardly sympathetic characters, and this may be why Omar hurls abuse at those who would mistake Zibahkhana for anything less (or rather, more) than a good old-fashioned horror film.

After a brief tangle with the board of censors, who rejected it outright at first, Zibahkhana opened in Pakistan at a cineplex in Rawalpindi. Remarkably, it was certified for “General” consumption. Rawalpindi is Islamabad’s older, louder, dustier sibling, a city in comfortable disrepair and renowned for a brand of illustrated cigarette lighter that comes in three main designs — Osama, Benazir, and Musharraf. The film was a mad success, running for ten straight weeks. A private screening for students in Lahore turned into something of a riot. Outside Pakistan, Zibahkhana has traveled to dozens of film festivals, horror and otherwise. At last year’s Fantastic Film Festival in Austin, Texas, it won the award for Best Gore. This year it took the top prize at RioFan, the Brazilian festival of fantastic cinema.

Certainly, there were setbacks. Zibahkhana’s Lahore release coincided with Benazir Bhutto’s assassination, and the film was promptly pulled. The Pakistani commercial rights — DVD included — were negotiated hastily, resulting in little revenue. Then there’s the small matter of the seventy-five thousand dollars invested in the film that’s yet to be recovered. Still, the film made its mark in Pakistan, and in its own weird way, put Pakistani cinema on the map.

As is usually the case with Omar, there are plenty of plans in the pipeline. There are more film festivals to enter, screenings to attend, and awards to collect. There is a suitcase full of scripts waiting to become films, including Jhabarjhilla, a genre-busting women-in-prison meets porn-factory meets monster-spectacular. There are films new and old to be reviewed for the website; new ice cream flavors to be invented; a possible new source for vanilla beans to be explored. In short, the mundane work of magic-making. And through it all, there is a small but determined army of Omarites, in Pakistan and beyond, following his every move.