In the stillness of the house at Aït Oumghar there are ghosts of cats. In footage captured of the writer and filmmaker Ahmed Bouanani not long before his death in 2011, the cats — at least seven — swirl around his feet and jump onto his lap when he sits, wrapped in a blanket, to read. He is frail, hermit-like; there is an elegant nobility to his bearing, “like an emaciated Brahman,” as a friend wrote, or like a certain prophet who would rather cut off his sleeve than disturb the feline sleeping upon it. Some called him “Sidi Ahmed,” imbuing him with the title of a holy man. Those who had known and venerated him were discouraged from trying to find him in his retreat in a remote Berber village in the High Atlas. Rumors circulated that he was dead, he was ill, “drunk from morning till night,” bad-tempered, misanthropic; that it was impossible to pin his geographical coordinates on any map. Even in Aït Oumghar, few knew that anyone lived in the house, for it was said Bouanani never went outside. His books — the very few published in his lifetime — were equally hard to locate. It was nearly impossible to find a copy of L’Hôpital, published in Rabat in 1990, Les Persiennes (1980), Photogrammes (1989), or Territoires de l’instant (2000), titles that saw the light of day only because they had been pried from Bouanani’s hands by friends and admirers. No images of the author circulated. In the rare event of a review in the press, it might be accompanied by a picture of the wrong Ahmed Bouanani, a television host with the same name.

Bouanani had gone into occultation in 2003, following the death of his youngest daughter Batoul after an accident in their home in Rabat. He left behind the city where he had lived for forty years, and with it, the archive of a life of unceasing creativity, which remained in his flat on the Rue d’Oujda, collecting dust. He left behind hundreds of reels of 35 and 16 mm films on the balcony that had once masqueraded as a dressing room; the costumes his wife Naïma Saoudi had dyed in the bathtub; the props and backdrops, impossible for an outsider to decipher their use. He left behind the thousands of books in his library; the boxes of illustrations and comics he sketched, the old photographs, film posters and playbills. And he left behind the stacks of his manuscripts, written in black or blue ink in a steady, cursive hand and never published: dozens of novels and screenplays, hundreds of poems, short stories, journals, a history of Moroccan cinema, a chronicle of Morocco itself.

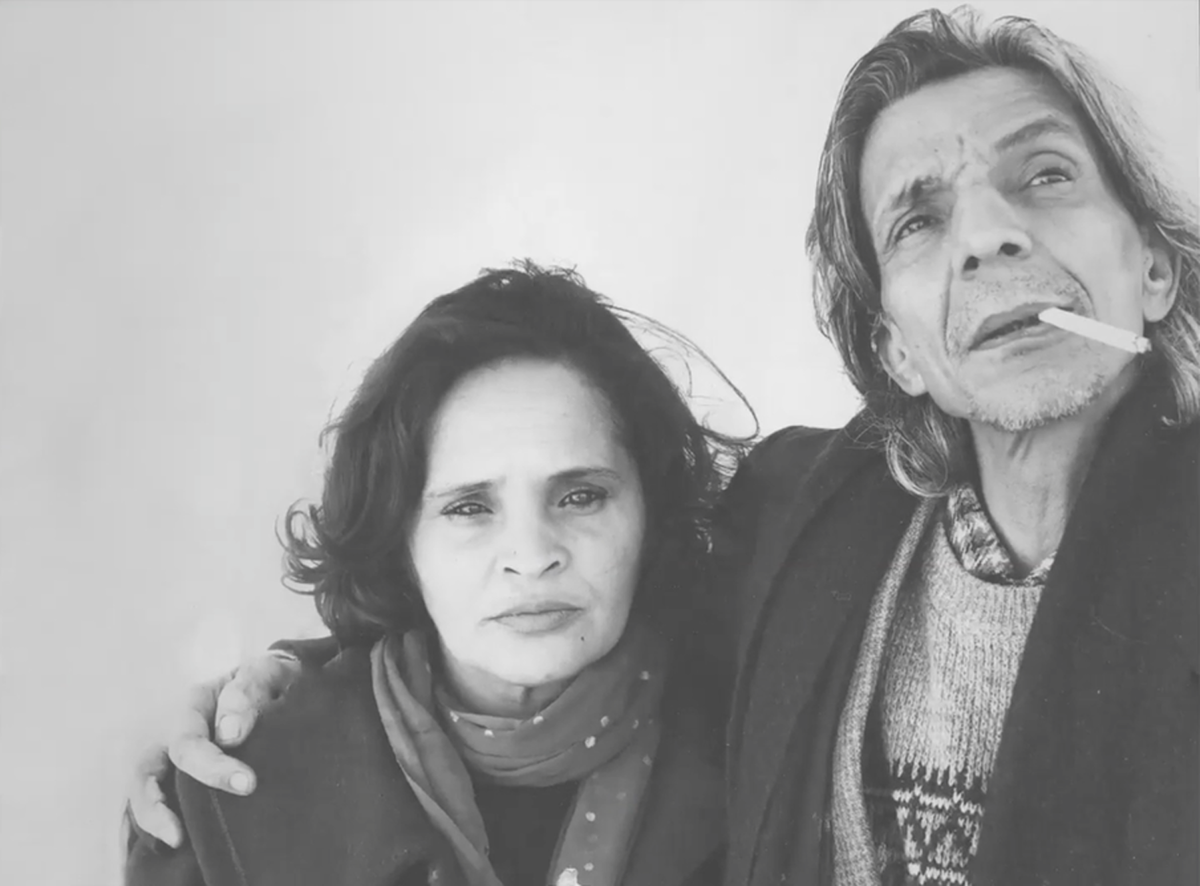

From the terrace of the mud-brick house at Aït Oumghar, the view looks out over grape vines and olive trees without end and fields of gourds, fed by the abundant waterways of a spring. Donkeys, sheep, and quiet children slink through the winding dirt alleys, past crumbling houses stamped with red handprints to keep danger away. A gigantic nest crowns a whitewashed minaret: the work of a stork, impervious to the megaphones that call the village to pray. On a cold day in 2014, I visited the house with Touda Bouanani, Ahmed’s older daughter, a brilliantly imaginative filmmaker occasionally known to dress in drag as the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. At the time, we were both artists-in-residence at Dar al-Ma’mûn in Marrakech, a few hours’ drive from Aït Oumghar. Touda strikingly resembles her father, in her features and her sage-like presence. As the last surviving member of her family, she is the guardian of its memory. Through her, stories rise to the surface, a bit like Melville’s Ishmael, afloat on the coffin and quoting Job: “And I only am escaped alone to tell thee.” I remember a portrait of her parents, drawn by Ahmed, watched over us in the kitchen. Naïma, a set designer and actress who died in 2012, was depicted as twice Ahmed’s size. She stared out at us and smiled; Ahmed was turned inwards, as if to bury himself in the folds of her scarf. His hair was a tangle of caterpillars. His eyes were looking down or were shut, against what he calls in The Hospital, in Lara Vergnaud’s translation, “the world’s angry and defeated face” — a face that he could never get used to.

In 1938 on the night I was born

this country had no more ancestors or History

It was a garbage dump where soldiers on the run

waded in grime and worshipped a deity

who, deaf-mute, twirled in the clouds

among locusts and naked angels

— from “Generation” by Ahmed Bouanani, tr. Emma Ramadan

Ahmed Bouanani was born on November 16, 1938 in Casablanca, a colonized city on the verge of war. Through the shutters of his childhood home on the Rue de Monastir, he could observe his surroundings without being seen. His was “the generation born of the marriage of the locust and the louse,” as Bouanani would say, an unholy union between a species that nests on the surface and one that swarms from above. In 1912, Morocco’s Sultan ‘Abd al-Hafid was forced to sign the Treaty of Fez, transforming the kingdom into a French “Protectorate,” with limbs ceded to Spain. While the French decided to preserve the pageantry of the Moroccan palace, it was only a mirage of sovereignty, for true power now lay elsewhere. In modernist office buildings in the new capital of Rabat, a parallel government was erected to control the colony and subdue its insurrections. Within the vast bureaucracy, Bouanani’s father worked as a police officer.

World War II brought American soldiers to Casablanca, along with air raids, famine, and chocolate bars. While Moroccans across the country rose up in scattered revolts against the colonial overlords, thousands of others fought and died alongside the Allies for meager pay. A bomb fell on the house next door; Ahmed and his older brother M’hamed made the war into a game. “Little Soldier Ahmed wears the shoes of a former combatant, he feasts with his eyes on Superman in front of the Cinéma Bahia where a police officer whips the crowd squabbling around the cash register,” Bouanani recalls in Les Persiennes, or The Shutters, as translated by Emma Ramadan, a collection of poems in which childhood memories appear like butterflies pinned in a box. His grandmother Yamna, “the strangest being in the house,” could still remember the French conquest, and taught her grandson that the souls of dead ancestors hid in the iridescent shells of beetles. Ahmed was sent to study with a Qur’anic teacher with a particular zest for doomsday. Gog and Magog lurched freely in the classroom as American zeppelins menaced overhead.

With the end of the war, the Moroccan nationalist movement stepped up its calls for independence, which were met with violent crackdowns and arrests. Although they demanded a democratic future for Morocco, the nationalists, to conjure support, drew upon the figurehead of the Sultan, Muhammad V, who occupied a nearly mystical stature in the popular imagination. In 1953, following massive demonstrations in Casablanca that were brutally suppressed, French authorities staged a coup, banishing the royal family to Madagascar. Moroccans across the country were outraged. It was said that the exiled sultan appeared in the moon; at night people climbed up to the rooftops for a closer look. Demanding Moroccan liberation and the sultan’s return, roving militias attacked police officers and government bureaus. In the violence that ensued, thousands were killed.

The crowd on the sidewalk. Around a red circle. At eight in the morning. Eight fifteen in the morning. January of… Someone had grabbed his 7.65mm revolver hidden in a pile of mint…. He fires the only bullet…. And the sun felt dizzy. Morning no longer knows which way to turn. The entire city, the walls, the lights, the new sky where the stars barely had time to turn on. Everything falls in front of my bicycle. Collapses. A police officer stops me. No, let him go, it’s his dad. It’s my dad. And the entire city says that it’s my dad.

— from “The Shutters” (1980) by Ahmed Bouanani, translated by Emma Ramadan

In early 1954, amid the wave of nationalist attacks on policemen, Ahmed’s father was assassinated on the street not far from their home. Ahmed, who was sixteen at the time, did not witness the shooting but arrived soon after, and saw the stains of blood on the sidewalk. The killer was never arrested and his identity would never be known. “I began writing after my father died,” Bouanani would recall in a journal entry. “Today I would say that writing was a refuge from my distress. But at the time, it was the legitimate ambition of an adolescent who wanted to get out of adolescence, who wrote, in his grand naiveté, also legitimate, on the first page of one of my middle school notebooks: ‘I want to be Victor Hugo or nothing.’”

The following year on November 16 — Ahmed’s seventeenth birthday — the Sultan, in his fez and sunglasses, stepped off a plane and onto Moroccan soil again, called back from exile by the French in a desperate attempt to restore order. Greeted by enormous, rapturous crowds, Muhammad V announced the end of the Protectorate: a few months later, Morocco became independent. Bouanani, by all accounts a diligent student, finished his baccalaureate, and left Casablanca for Paris in the early 1960s to study film at the prestigious Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques. As soon as he received his degree, he returned to Morocco, eager to contribute to the cause of a new, national art.

Upon his return from Paris, with few other prospects for employment, Bouanani took a job at the Centre Cinématographique Marocain (CCM), where he would remain for thirty-two years. In addition to its appointed role as film regulatory institute, the CCM produced short films that promoted a sense of national identity. Bouanani also took on work for several government-sponsored heritage projects. On assignment to document villagers in the town of Imilchil as they picturesquely toiled away at handicrafts, he was appalled to find soldiers supervising them with guns — and so he filmed them, too. When Bouanani screened it for his bosses at the CCM, they berated their employee for “spoiling” the image of Morocco, and the film became Bouanani’s first, of many, to be banned.

It had not taken long for the glamour of independence to fade. Following the death of his revered father, Hassan II had risen to the throne. The regime grew ever more repressive; in 1965, after a student-led uprising paralyzed Casablanca, thousands were killed, imprisoned, or disappeared. The brutal suppression marked the beginning of Morocco’s années de plomb, or “years of lead.” On national television, the king attacked the students who had provoked the revolt. “Allow me to tell you,” Hassan II announced, “there is no greater danger to the state than the so-called intellectual; it would have been better for you to be illiterate.”

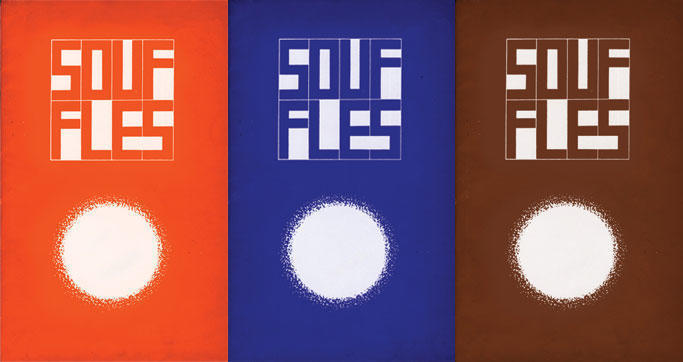

For a generation stuck between locust and louse, the uprisings marked a political awakening. The following year, a group of artists and intellectuals established the radical journal Souffles, to which Bouanani contributed several poems and essays. In his manifestos, the editor and poet Abdellatif Laâbi railed against the stagnation of Moroccan thought and called for the total decolonization of culture and art. Yet what foundation was left upon which to build a national culture? What bound Moroccans together as a nation? After all, it was the colonizers, Laâbi wrote, who had come up with the boundaries of nations, artificial divisions that retraced the history of conquest and dismembered tribal territories. What made Morocco a unity beyond a shared history of defeat? “Are we really a people?” a patient called Le Pet (“Fartface)” fumes in The Hospital. “Think about it. We were born with our right hands outstretched, begging in our blood, not to mention cowardice, infamy, and fear… We don’t even know how to talk anymore, our people’s pitiful vocabulary barely fits in the palm of my hand.”

Sometime in the autumn of 1967, Bouanani caught tuberculosis and ended up in the Moulay Youssef Hospital in Rabat. He wrote letters to his wife Naïma, who had just given birth to Touda the previous year. For six months, Ahmed stared up at the ceiling from the hospital bed, with no sense of when he might escape.

This Saturday 9 December,

… Boredom has long, long legs and a cold, harsh head… Even photographs are terrible to see. When will I return to their world? Maybe… and maybe.

I wasn’t able to write a single word Sunday, and it’s even colder today. Earlier it was like the end of the world. In my cold little planet, I’m thinking of you. Warming my poor body beside yours, penetrating your blood in search of the sun. Thousands and thousands of times I hold you against my sick chest, I lose myself in your hair, in your eyes, and in your hips and in your stomach. My life stops and I have the entire universe in my head. My desire would endlessly fill the pages. One must shut up to hurt less.

Write me, tell me about your day, tell me about Touda’s world. Take time to write to me.

The one who wants you,

you, always beautiful, always happy

Ahmed

“It’s cold here too, like in my memory,” the narrator writes in The Hospital. “No chance of nestling into the soft belly of an illusion.” A swarm of of insects ripples through his dreams, different species of butterflies “that my naked body attracted like a light.” He is amazed he can still remember the names: “Urania, Vanessa, Bombyx, Argus, Machaon, and Phalene specimens.” Armies of caterpillars creep along the contours of the night. When Bouanani was released from the hospital in May 1968, he received a certificate of good health authorizing him to return to work. The slip of paper, which Touda found years later, was signed by a certain Dr. Papillon, or Butterfly.

“Who was Caesar then?” Touda asks her father in footage captured in Aït Oumghar. “Ghannam,” he replies. “And Hassan II.” Not long before he was exiled to the TB ward, Bouanani suffered a banishment of a different sort. Although deeply political, the filmmaker preferred to float above party politics, and resisted any affiliations. Yet when Omar Ghannam was appointed as director of the CCM, he deemed Bouanani a subversive element and ordered him to cut his long, flowing hair. Banned from directing any more films, Bouanani was relegated to the dusty archive department, and permitted only to work as editor. Yet surrounded by reels of moldering footage — documents of the French invasion and its “civilizing” mission — Bouanani soon realized that editing could be a way to elude censorship, and an art form of its own. He would resurrect the old newsreels, from the CCM collections and others he found on the site of a dismantled production studio, some so faded they appeared as ghostly white. Behind closed doors, like a spider he began weaving together archival footage into a clandestine, feature film Mémoire 14, which told the story of Morocco’s subjugation and reflected upon its present day.

In the early 1970s, an increasingly autocratic King Hassan II led a movement to Arabize collective memory: to erase the deviation of colonialism from Morocco’s history and eschew European curricula in schools. The record of national memory would begin only in 1956. To speak of anything earlier became taboo, and in particular any mention of a certain, ill-fated “Rif Republic.” In 1921, the editor-turned-guerilla Abd el-Krim led a revolt to liberate the mountainous region of the Rif from Spanish and French rule. After a series of unlikely military victories, Abd el-Krim established the independent Republic of the Rif, which began to print its own banknotes, appointed a Prime Minister, and sought diplomatic relations abroad. After five years, European forces succeeded in violently suppressing the Rifians, using chemical weapons. Exiled to the Indian Ocean, Abd el-Krim became a hero of anti-colonial resistance everywhere. As the Rif Republic’s memory could not be spoken aloud, Moroccans used folkloric names to refer to the period, as Bouanani captured in “Mémoire 14,” a 1969 poem recited in the film that shares its name:

Years of the gazelle,

years of the locusts,

year of the sword and the canon,

year of the fair season.

Our blood still tastes like legend.

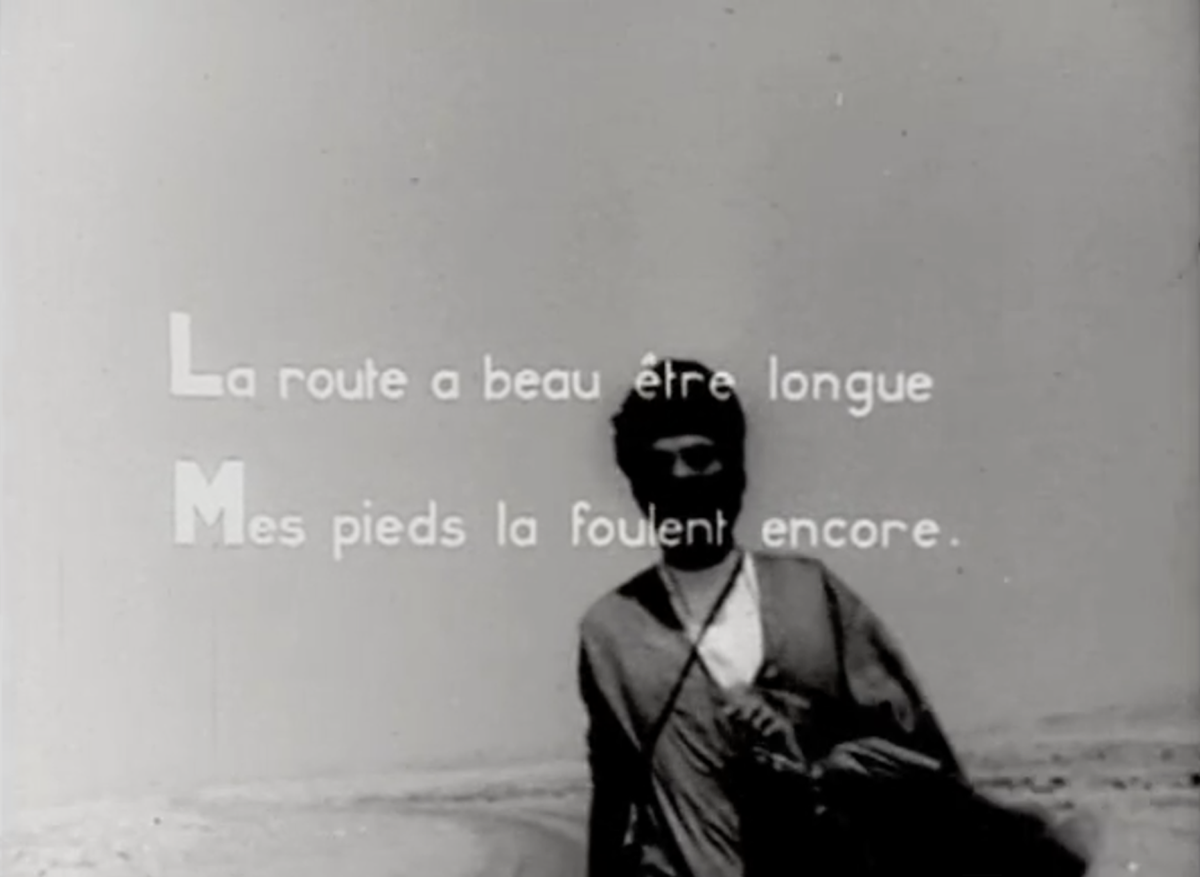

The number fourteen conjures a conflicting way of measuring time, as the Islamic fourteenth century A.H. corresponds to the twentieth century C.E. — the designation ever prompting the question, common to whom? The dueling systems of timekeeping destabilize any authority time itself might have, that “invention of adults” which twists into absurd shapes in the eternity of a hospital ward. In the footage of Mémoire 14, reptilian army tanks scale a desert ridge; a man runs with a lamb in his arms as bullets fly; a plague of locusts descends upon the fields; the Sultan, swathed in white, appears beneath his parasol; a camel is shot in the head.

In 1971, Bouanani finished Mémoire 14, with a run-time of 108 minutes. Yet Ghannam found it inflammatory, and ordered him to redact vast sequences, especially the footage from the Rif War. With each new cut Bouanani screened, Ghannam demanded further censorship — and that the outtakes must also be burned. What was left of the film was a mere 24 minutes. “Our memory is long-lasting,” the narrator wryly declares. As Bouanani recalled to his friend Essafi, the tyrant Ghannam remained displeased by the film, threatened to fire him, and to see that Mémoire 14 was destroyed. It was, fittingly, the intervention of history itself that rescued the film. Ghannam was invited to a birthday party for Hassan II in July of 1971, an extravagant feast held in the seaside palace at Skhirat. Just as lunch was served, a thousand mutinous soldiers stormed the banquet, overturning tables and raining bullets onto the guests. The King and his family escaped, yet nearly a hundred revelers were killed — Omar Ghannam among them. The first line of Mémoire 14 repeats as its last: “Happy is he whose memory rests in peace.”

In the wake of the failed, bloody coup, soon followed by a second attempt, the response from the palace was immediate. Suspected plotters, traitorous generals, and large numbers of left-leaning intellectuals were rounded up and forcibly vanished. They would be incarcerated in secret desert prisons that would only become known to the public in the 1990s, when the inmates who were still alive were released. Most infamous was Tazmamart, a remote sepulcher where hundreds of Moroccans were left for nearly two decades to die a slow death, confined underground in isolation, without light or basic medicine. Among the incarcerated was Naïma’s brother Nourredine, a student at the time. After disappearing for two years, he was discovered languishing in Kenitra jail; over the course of his ten-year imprisonment, Naïma and Touda were able to visit him. With him in Kenitra was Abdellatif Laâbi, whose 1972 arrest put an end to Souffles. In a poem in their honor, Bouanani wrote:

As soon as the guards turn their backs

he flies

he comes to greet us…

The birds know you

There are shreds of cloud in your beardwipe them off before going back to the walls

Happy are my friends

the poet prisoners

for beneath the earth they see

much further than us

In 1979, after a succession of further tyrants at the CCM, a new, sympathetic director was appointed, Bouanani received a raise, and he was finally able to make what would become his only feature film — the cult classic al-Sarab, or The Mirage. In the opening scene, two men haul sacks of flour along a hillside path, and argue over whether a cherished donkey may be buried in a cemetery. Will donkeys be admitted into paradise? Their conversation evokes the Prophet’s night journey to heaven aboard the winged steed Buraq, the ascent known as the miraj — a word so close in sound to mirage — from the Arabic root “to rise.” One of the men, Mohamed, discovers bankrolls of dollars hidden in the flour. He sets out for the city with his wife Hachemia to exchange them for dirhams, in a quest reminiscent of Arabian Nights tales of men seeking their fortunes abroad. On the bus to Salé, they encounter a ragged, raving messiah who captivates Hachemia. “At the resurrection, everyone will have the same face,” he preaches to his followers. Meanwhile, Mohamed is too afraid to enter any bank, fearing its European clerks will assume he stole the money. When he meets Ali Ben Ali, a mysterious magician who claims he can help him, the naive Mohamed is drawn into a shadowy underworld of dissent, although its nature is never made explicit. Inside Ali’s hideout is a gigantic canvas of Buraq — painted by Naïma.

Though the action is set in 1947, the film seems to juxtapose two eras: a Protectorate past and the unspeakable oppressions of the years of lead. Mohamed discovers Ali lying in a dark passageway, gravely wounded, alongside other men, evocative of political prisoners. “May our powers of resistance equal our suffering,” the magician declares, rousing the men from their abjection. A Satanic child with an ancient laugh cackles at Mohamed, sending him into a panic. “I am just a poor man… I don’t mess around with politics,” he cries. When he escapes the tunnel, the world outside is in ruins; the grass has grown tall as if years have passed in minutes. He finds Hachemia with the holy man and his circle, deep in an ecstatic, communal trance. They reunite on the beach, in the warmth of an abandoned bonfire. Mohamed’s money was an apparition all along, concludes the sardonic fable of The Mirage. “My only ambition — and it’s the ambition of all Moroccan filmmakers — is to get audiences used to seeing themselves and their own problems on the screen, and from that, to be able to judge themselves and the society in which they live,” Bouanani would say in an interview. “The screen must cease to be the privileged mirror of foreign countries.”

No creature appears more frequently, across Bouanani’s oeuvre, than the one with a horse’s body, a woman’s head, angel wings, and a mane as long as a cloud. Buraq is the winged embodiment of love, a symbol of the sacred that outstrips all religious authority. She transcends the dour theologians who despise her because her name appears nowhere in the Qur’an. In Bouanani’s short story “The Resplendent Chronicle,” a dissident scribe named Malek is wounded by an assassin’s dagger, and is found in a pool of blood, still alive. On his deathbed, Malek gives his son the keys to the barn, where he housed a secret vehicle — the Buraq. His son, Kacem, unlocks the door to the stable, mounts the steed, and zooms off into the night. Centuries ago, when Buraq took flight with the Prophet Muhammad on her back, it is said she knocked over a jug of water with her hoof. When they returned to earth, having visited the seven levels of heaven and conversed with God Himself, the Prophet intercepted it before the water spilled out. Yet when Kacem descends from his own astral journey, he finds, instead, that his father’s house is aflame. “A gigantic blaze illuminated the sky. Everything around him was burning: the house, the books,” Bouanani wrote, painting a scene that would prove eerily prescient. “The acrid odors of paper and flesh were wafting from the gutted ruins.” For Kacem, everything is lost — his father’s manuscripts, the relics of his childhood — except the Buraq, his inheritance, the creature that is his burden and his escape.

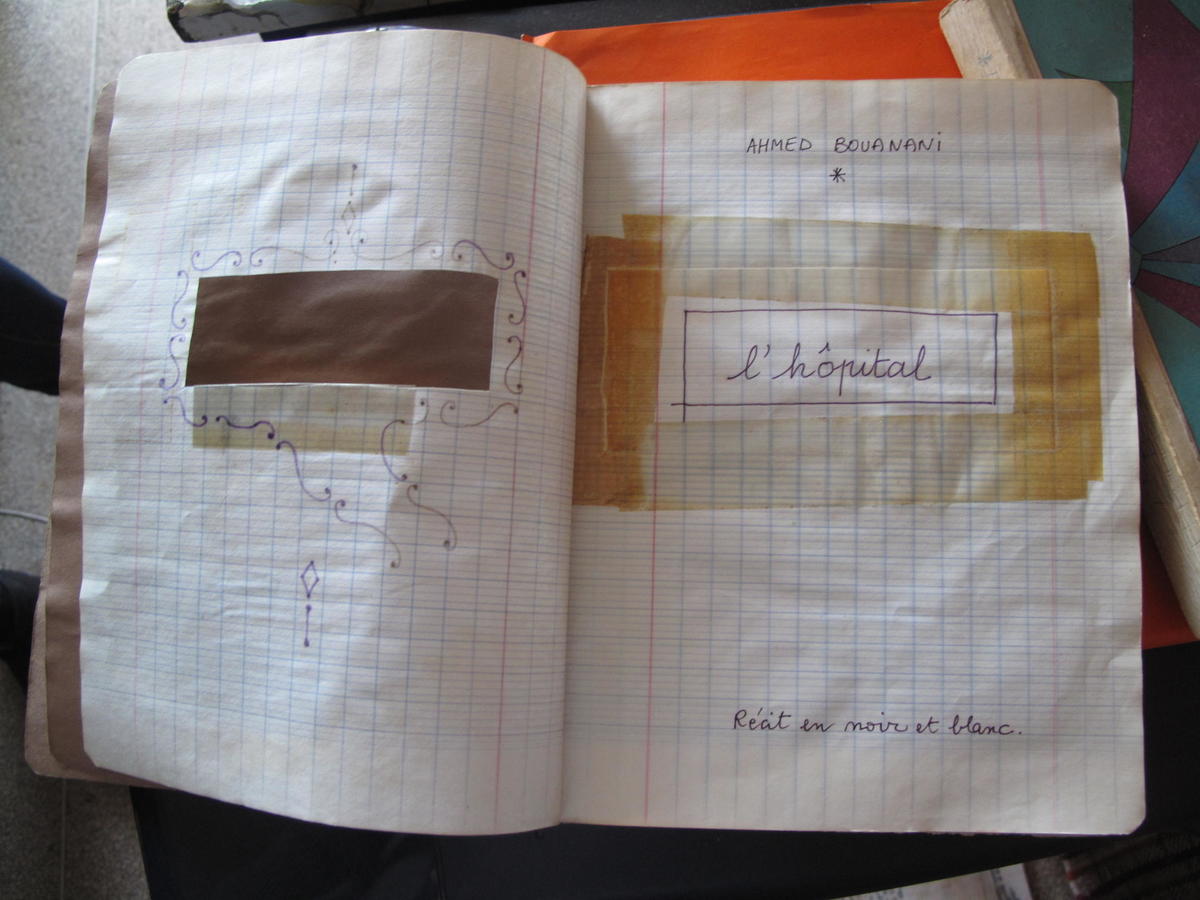

Late in the night on July 23, 2006, a neighbor in Rabat called Ahmed and Naïma to tell them that their apartment was on fire. It started on the balcony and first consumed the reels of films, the props and costumes, before spreading to the library, the boxes of manuscripts and photos, incinerating the bicycles, the television, and ultimately destroying half the flat. Its cause was never determined. “Sheets of paper fanned the flames,” the police report concluded. What wasn’t turned to ashes was drenched in the water that quelled the fire. Ahmed could not bear to see it; it was Naïma who returned from Aït Oumghar to sift through the heaps of charred rubble. While the computers had melted, she found that many of Ahmed’s handwritten manuscripts had miraculously survived unscathed, among them several wrinkled drafts of The Hospital. On the cover page of Le Voleur de mémoires (The Thief of Memories), the trilogy he labored at for over thirty years, water had begun to wash away the blue ink of the word “Mémoires,” but the text was still intact. Naïma found the slightly charred pages of Un linceul pour Naïma (A Shroud for Naïma), a novel Ahmed had written in 1971. She salvaged the waterlogged draft of Une Ville sous le soleil (A Village Under the Sun), so damaged that the pages, with their lines of perfect handwriting, had become translucent. She unearthed a scorched and molten Gallimard edition of Borges’ L’ Aleph that was still, somehow, legible.

A certain winged steed had also survived the flames. In the wreckage was the kitschy poster of an ornate, pink Buraq, decked out in jewels, with long black hair and heavy makeup — the model for the canvas Naïma painted for the set of The Mirage. There was a creepy image of a pink and green, scaly Satan stabbing Buraq in the heart. There was Ahmed’s drawing of Muhammad — he had drawn half the Prophet’s face — astride the Buraq and amorously embracing her. And there was a drawing of the celestial creature knocking over the jug. Spilling from it, in Bouanani’s depiction, are sentences: words that flow into the waiting pages of a nearby book. The picture itself had been soaked with water. Naïma dried Ahmed’s surviving papers in the warm July sun, page by page.

In Rabat, rumors circulated that Bouanani had died in the fire. Yet in the years that followed he was spotted at least once in the city he had forsaken — in a hotel elevator. Ali Essafi remembers bumping into him. “His body was like that of a ghost, but his spirit was lively, and his hand gestures elegant. His gaze remained youthful and piercing…” Essafi was accompanied by a film festival director and proceeded to make introductions. “My companion looked at Bouanani anxiously, and after fumbling for words, he asked: ‘So you’re alive?’ Bouanani’s answer was a mischievous smile.”

The Hospital, the only novel Bouanani published in his lifetime, is a parable of resurrection. It unfolds within a labyrinth, a tomb that exists outside of time, whose inhabitants dress in “blue, two-piece shrouds.” It is set within the enormous and failed infrastructure of an authoritarian state. Trapped in an unlivable present, the narrator will try an ascent, an abortive, feverish miraj, though he will not even scrape the bottom of heaven’s outermost ring. “I glow bright as a star, I rise above the room to where I can barely hear my companions’ breathing or snoring, I gently flatten myself against the cold ceiling, turn around so that I can look down upon the beds…” he relates, before he flops back onto the medical cot. What The Hospital attempts is a resuscitation of memory: of a childhood pronounced dead and the collective memory of a kingdom forced to erase its past. “I admit to being a great amnesiac,” the voice in Bed 17 relates. “My memories resemble ruins eroded day after day.” The inmates, like scrappy Scheherazades hooked up to IVs, tell each other well-worn tales to fight against the forgetting. In a place where memories become “bleach-flavored,” their dialogue is full of vivid lists of nouns, as if taking inventory of a vanishing world.

The patients take pleasure in it: if nothing else remains for them, they can at least wrest back the words for things from oblivion. What emerges from their lists is a hospital that hardly seems sterile at all. It has a fantastic garden. “All this vegetation around us! A caprice of a mad gardener…” the narrator shouts. He begins to taxonomize. “Look around, we’re not just talking oaks, pines, palms, or harmless poplars. There’s also calabash, rubber, sumac, jackfruit, manchineel, sequoia, and baobab trees, and God knows what else! Not to mention the thousands of exotic flowers that have no business in a hospital.”

But if the The Hospital represents an excavation of memory, but it also poses the question: what’s the point? Why bother remembering, if at the resurrection, as Bouanani reminds us time and again, everyone will have the same face? Resurrection is the reawakening of the dead; the springing back into gear of joints and sinews unused for centuries as everybody gets up. But resurrection is also the resurgence of camaraderie, of communalism among the living, out of a crater of despair. The marginalized, impoverished, illiterate inmates of the hospital, abandoned by doctors and nurses, band together in unlikely friendships as they weather the freezing winds of a storm. They turn their meager meals into imaginary banquets; they mark occasions with grandiose speeches, like kings. They remind us, at every turn, of their humanity. In the end, The Hospital is not about what we owe the dead but about the barest minimum of what we owe the living. It reminds us that the afterlife is not only some shade of existence, postmortem, but also the collective living on — the continuing generations to follow our own. For their sake, it asks how to mend a country, when the rubble of whitewashed memory is the only material at hand.

It was, by all accounts, a rather exciting moment to leave the planet behind. On February 6, 2011, the world was transfixed as it watched the uprisings of the Arab Spring. Only three weeks earlier, Tunisia’s longtime dictator Ben Ali had been ousted by the protests ignited by a street vendor, who lit himself on fire. In Egypt, the Battle of the Camels had been fought in Tahrir Square, but Hosni Mubarak had not yet been toppled. In Morocco, protesters were just beginning to organize into what would form the February 20 Movement, later to be deftly contained by King Mohammed VI. Yet at this moment of political awakening and hope, Bouanani, ever the nonconformist, made his exit. When his death was announced, people mourned the wrong Bouanani, the TV host with the same name.

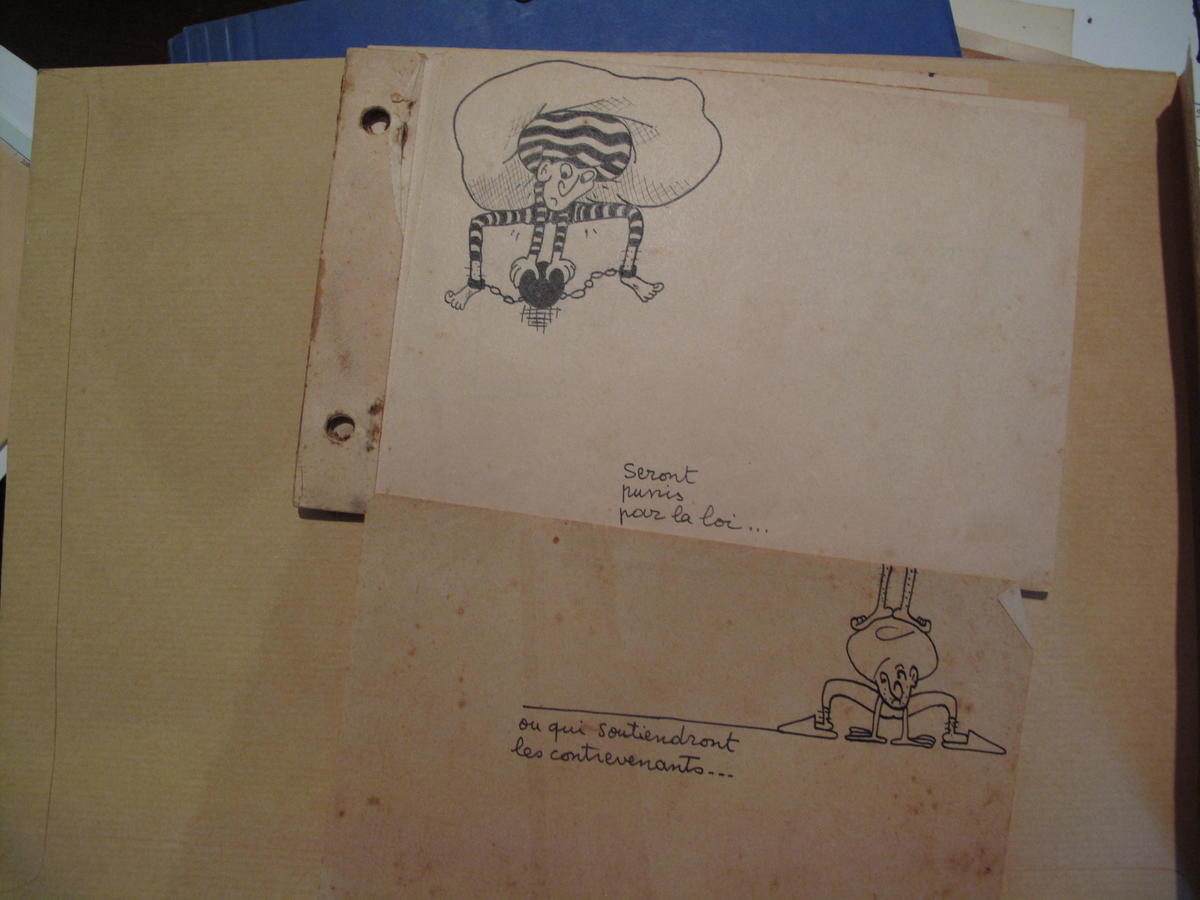

When Fernando Pessoa died in 1935, he left behind a legendary wooden trunk, filled with 25,000 pages of unpublished texts and fragments, some posthumously collected in The Book of Disquiet. Inspired by Pessoa, Touda Bouanani has transformed a painted chest from one of her father’s film sets into a trove for his papers. The ornate trunk appeared in the esoteric Les Quatre Sources (The Four Sources, 1977), Bouanani’s only experiment in color, which starred Naïma as a wild sorceress. In the film, the trunk concealed a sword passed down from a father to a son; for her own part, Touda is only just beginning to reckon with her father’s legacy. If Bouanani seemed to reject the idea of publishing, rather than face the censorship that plagued his films, the text themselves tell another story. Though written by hand, certain manuscripts are formatted as if they were published books, with lists of front matter — “Previously Published” and “Forthcoming” — detailing titles that Bouanani would never see printed in his lifetime. For nonfiction works such as The Seventh Gate, his history of cinema in Morocco, Bouanani diligently prepared the indexes. Many of the drafts of novels, poems, and stories are illustrated with his drawings, of turbaned theologians, snoring peasants, mythic beasts. Among the papers is a copy of the first edition of Les Persiennes, which appeared in 1980 when Ahmed’s daughter Batoul was eleven. She colored in the pages with bright magic markers, transforming the first page of her father’s tome into a hybrid chicken-goat with claw legs. Later, in 1999, Bouanani would properly inscribe the copy to his daughter, four years before her sudden death: “For my Batoul, some lice and vowels from an earlier time. With an affection and a love that knows no limit —”

“Happy are those who can make of their suffering something universal,” reads a scrap of paper from 1913, unearthed in Pessoa’s chest. Over forty years of letters and moving pictures, Bouanani’s elements remained remarkably consistent: a 7.65mm bullet, the sound of swallows, the view, half-light, half-shade, through the blinds. He leaves us with a corpus deeply evocative of his own Morocco, its particular species of lice, angels, and flies. Yet out of his strange alphabet, Bouanani has created a body of work that has withstood every torment of time. In the face of a world that remains angry and defeated as ever, Bouanani points us in the direction of the sacred. He passes along the keys to the winged steed to us. “I sometimes think I see that civilizations originate in the disclosure of some mystery, some secret,” Norman O. Brown once wrote. “There comes a time — I believe we are in such a time — when civilization has to be renewed by the discovery of new mysteries… by the undemocratic power which makes poets the unacknowledged legislators of mankind, the power which makes all things new.” Ahmed Bouanani is such a mystery. Confounding archangels and autocrats, fire, water, and censorship, he rises, resurrected from the fragments of memory.

This essay is adapted from the introduction to The Hospital by Ahmed Bouanani, translated by Lara Vergnaud and published by New Directions Press in 2018. Thanks to Touda Bouanani, Omar Berrada, Ali Essafi, Joshua Richeson, and everyone at New Directions.