Tucked away behind the gleaming showcases of the Metropolitan Museum’s recently renovated Islamic art galleries, a smaller space hosts a handful of contemporary Iranian artworks.

Parviz Tanavoli’s bronze Poet Turning Into Heech presides in phallic glory over a glittering constellation of familiar names: grande dames Shirin Neshat and Monir Farmanfarmaian and rising stars Ali Banisadr and Afruz Amighi are rounded out by Y Z Kami, a painter of quiet but steady repute. All of the works were made in the last two decades, but this seems to be the only thing they have in common; each work takes up a different medium, theme, and stylistic approach. The artists themselves share neither generational concerns nor, as implied by their location in the museum, religious references. And yet there is another, unremarked, commonality to the works of these highly acclaimed artists — the obliqueness of their relationship to the country whose history and traditions they take up in their work.

Tanavoli, a major figure in Iran since the 1960s, became an international name when a monumental 1975 bronze sculpture broke auction house records at Christie’s Dubai in 2008 (to the tune of $2.8 million); he has lived in Vancouver since 1989. Farmanfarmaian, who first moved to New York in the 1950s, has been between continents ever since (more so in the past decade, after the rediscovery of her work by the new Middle Eastern art markets). Kami, Banisadr, Amighi, and Neshat all live and exhibit in New York. Neshat is arguably the most visible Iranian representative of what we might call the Imaginary Elsewhere. Her work was central to the Museum of Modern Art’s 2006 show Without Boundary, one of the first major attempts to assemble a canon of Middle Eastern contemporary art. The Asia Society, currently planning a large exhibition of Iranian art, inaugurated the project with a lecture each by Farmanfarmaian and Tanavoli.

Shows of this sort may do little to reconfigure the way we think of Middle Eastern art: the mainstream art press duly registers their tokenistic praise, sending out ripples of envy and/or contempt among artists not included, and pats on the backs of those involved. But these shows and their high-gloss museum catalogs are, in the long run, the authors of art’s history. All the hopes pinned on new Arab museums, plucky journals, and gallery monographs notwithstanding, institutions like the Met and the MoMA have inherited institutional privileges that could take several generations to unseat. They are the aristocracy of the art world: dignified, antiquated, conservative, and imbued with generations of legitimacy. Their high-powered exhibitions of “non-Western” art conveniently erase the tangle of class, education, and circumstance that is the peculiar if common predicament of living in a cultural diaspora.

Consider, by way of contrast, the 2009 exhibition Modernism and Iraq — a carefully curated and thoughtfully presented show of painting, sculpture, assemblage, and even video from twentieth-century Iraq, organized at Columbia University by two established historians of ancient and modern Iraqi art. The work on view was idiosyncratic, vibrant, and occasionally dreadful; it was, in any case, unconcerned with explaining itself to the viewer. It spoke to local themes and pedagogic lineages. Some of the (living) artists were still based in Iraq, but not many of them would have been capable of representing Elsewhere in the manner of the artists at the Met; their work was simply too insular. Heroically itself, Modernism and Iraq slipped seamlessly from view, and few of its artists have turned up in New York galleries or museum collections since. For an artist to make it into a museum, her work must anticipate its ambassadorial function, representing whatever is happening Over There — say, in the region situated in gold lettering above the Met’s gallery entrance as “The Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia.” (Just don’t call it Islamic.)

The situation is a familiar one for the Bidoun reader. Much ink has been spilled scrutinizing the problems inherent in representing difference (or… anything at all) in museum settings. We love to complain about the potholes and dead ends of this road paved with good intentions. We’ve called it neo-colonialism, ethnic marketing, postmodernism or cosmopolitanism or hybridity, bourgeois-ethno-chic, opportunism. We have attributed this system of value to the commercial imperatives of auction houses and galleries. Despite routine protestations, we seem incapable of changing the terms of the conversation, and the backstage dynamics remain invisible to all but privy insiders with critical leanings.

But what is being rendered invisible here is more than institutional opportunism or fortuitous professional circumstances. For the diaspora artist — I use the term the way I would use “disappearing artist” or “trapeze artist” — the conditions of living or belonging Elsewhere have been skillfully translated into the poetics of representation. Hers is a distanced, self-conscious yet self-effacing belonging. Identity becomes emphasized because it is never a given. Not only must she construct her point of reference, she also needs to evoke a community that is too dispersed to be easily recognized. What the work of the diaspora artist represents is primarily its own diasporic condition. It performs public gestures of belonging, staging its loss so as to overcome it through visual pleasure. The diasporic artwork brings out the viewer’s deep desires — for roots, for poetic depth, for historic and political relevance — and then resolves the traumatic backstory with a neat visual twist. Its self-fulfilling premise and very public narcissism are precisely what appeals to collectors, curators, and museum audiences (and authors of art history textbooks).

The success of a diaspora artist depends less on subject matter than on the accessibility of their work. The true diasporic artwork can’t be too complicated. The sensory experience it invites must be available to all kinds of viewers. Allusions to biography, current events, or mystic philosophy are always good. Tanavoli enshrines “nothing” (the literal translation of heech); Farmanfarmaian shatters the viewer’s self-image with fragments of artisanal mirrorwork; Amighi gives us flitting shadows of abstract pattern to “represent… her native country’s turmoil.” Neshat simply gives us an icon: the chador-clad woman with a gun. Her black and white photographs are also self-portraits, though the artist herself does not wear a chador (nor, it seems safe to say, pray with a gun by her side). Neshat’s Woman of Allah is less an emblem of “Iranian women’s involvement in the Iran-Iraq war” than it is a rehearsal of viewerly expectations, partaking of stereotypes (or better yet, anti-stereotypes) of an Elsewhere that is more mysterious and relevant that our banal Here and Now. More importantly, the work stages the fulfillment of the diaspora artist’s wishes — for belonging and for cultural and political relevance.

This is not an attempt to draw lines in the sand between those who “authentically” belong and those who lack some essential cultural rootedness. True, the diaspora artist is often driven by the desire to reunite with, speak for, support, and/or extend the cultural Imaginary of the homeland. (In contrast, say, to the scores of young artists lined up outside European embassies in Tehran, Dubai, and Damascus who will only look back to the deep poetry of their homeland once they are safely ensconced in an MFA program abroad.) In fact, the diaspora artist often protests her representative status quite vehemently, sometimes parlaying it productively into the work itself (as with Emily Jacir’s 2001–03 Where We Come From, where the Palestinian artist uses her American passport to traverse borders otherwise closed to her.) I wish rather to introduce a new basis for understanding what I am calling the diasporic artwork: our deep attraction to the psychological pleasures of a substitute belonging.

Of course, there is already a word in our critical terminology for this pathological process: the fetish. In Fetishism (1927), Freud described the mechanism by which we ward off loss and protect ourselves from future trauma through fetish objects. “The subject’s interest comes to a halt halfway,” he wrote. “[I]t is as though the last impression before the uncanny and traumatic one is retained as a fetish.” Think of the cottage industry of tragic autobiographies by Middle Eastern women “in exile.” (Farmanfarmaian’s own charming tome, A Mirror Garden, is one of the better examples.) Child psychologist Donald Winnicott’s “transitional object” is another apt take on the diasporic artwork: it produces an illusion of the satisfaction that used to be provided by the now-absent mother (or motherland). Nineteenth-century psychologist Alfred Binet, one of the first to use the term “fetish” in a sexual context, liked to distinguish between “normal love” and “plastic love,” the latter consisting of a devotion to objects rather than people, to the part rather than the whole. “The love of the perverted is a play in which a minor character steps into the limelight and takes the place of the main character.” The story of loss is perverted and subverted in order to ward off future loss and give satisfaction through what Freud called “disavowal.”

Of course, “fetishism” is usually taken to be pejorative. And yet a fetish is also one of the most powerful examples of a social object, a material occasion for an individual to relate to the values of a collective Imaginary in a deeply personal way. Historian William Pietz gives an inventory of such occasions: “a flag, monument, or landmark; a talisman, medicine-bundle, or sacramental object; an earring, tattoo, or cockade; a city, village, or nation; a shoe, lock of hair, or phallus; a Giacometti sculpture or Duchamp’s Large Glass.” Our diaspora artist is in good company. Her fetish objects use personal disavowals as tools to create figures of collective history out of chaos and contingency. While there is some sleight of hand in what she does, in the best tradition of the historic fetish object — the Portuguese word feitiçio meant “magical practice” or “witchcraft” — there is also a great deal of personal truth.

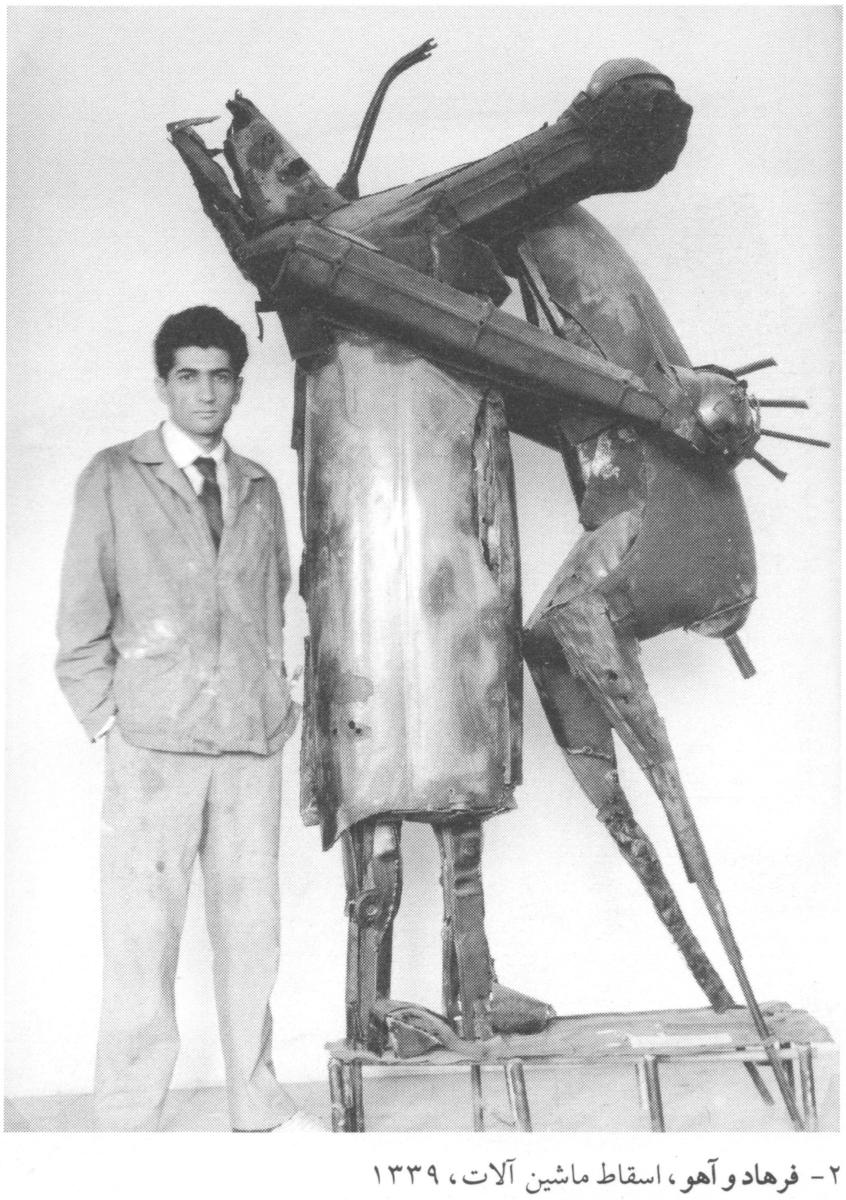

Acknowledging that the Elsewhere we encounter in the work of the diaspora artist is a complicated personal construction restores long-hidden nuances to their work. Talk of the fetish sweeps aside the dignified rhetoric that reigns in the thickly carpeted precincts of museums the world over. Parviz Tanavoli is celebrated for his bronze walls of illegible calligraphy — soaring monoliths of a lost culture, complete with high-cultural references and a twinge of pathos — which would fit in nicely in most any corporate lobby. But in the late 1950s, the young Tanavoli rebelled against both his conservative artistic training in Iran and the precious lessons of a residency at Carrara’s marble studios. He returned from trips to Europe and America — his first encounter with Elsewhere and its representation — ready to go it alone, using bits of scrap metal to make perverse robotic couples rife with sexual allusions, genitalia that curved out as spigots, and scatological references that summoned all the crude force of south Tehran. He is certainly worthy of inclusion in the both local and global canons — just not as a banal sculptor of decorative bronzes. Tanavoli recognized the logic of the fetish early on, and his monumental phallic bronzes need to be understood in relation to the larger iconoclasm legible in his whole body of work.

The diaspora artist produces a kind of collective statement that is even more valuable if understood for what it is: artwork that emerges primarily out of the conflict of individual desires. Art must be uncoupled from journalism: the Elsewhere the artist engages within her work is not a real geographical location; it is an imaginary place. The political import of these works has less to do with representation than with the pleasures and perils of storytelling, the effort to recast the everyday into mythical structures that speak to universal desires.

“They cannot represent themselves; they must be represented.” The epigraph of Edward Said’s Orientalism (a regrettable quote from Marx) springs to mind here, not only because the temporary exhibitions room at the Met is located near a small gallery of Orientalist paintings — dark-skinned men, bazaar and kitchen scenes, the occasional tiger in the wild — but also because Said’s ghost seems to be pacing these hallways, not quite sure of what to make of the turn of events. These exhibitions seem to offer a long-awaited shift in the power dynamic, as though the subjects of the paintings have emerged to speak for themselves. To denigrate their ability to represent their own reality would seem to be complicit with age-old histories written by the imperialist victors. Is it not time that “they represent themselves?” That is precisely my point here. If the Orient was a European construct, the subjects in Orientalist paintings mere imaginary screens for the projection of European desires, then turning the tapestries will result in portraits no less imaginary or constructed. And it is precisely this artificial, fantastical quality that needs to be discerned, and presented, clearing the way for a less coherent set of voices to emerge amid the museum hush.