There’s a Kuwaiti proverb: “All theft is forbidden except the theft of misabeeh.” So my Kuwaiti father tells me. A misbah (singular) is a string of prayer beads, like a rosary, used for prayer and meditation and for keeping one’s hands busy in times of boredom. My father is a misbah thief.

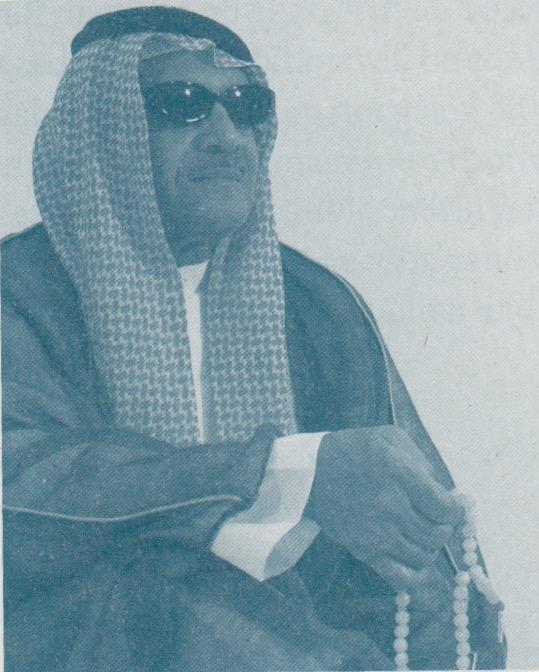

He steals mostly at the diwaniyah, where Kuwaiti men gather to talk politics, play cards, watch television, and generally shoot the shit. In this relaxed male environment, many a misbah can be found in a constant, generous, elaborate twiddle. If he’s given the opportunity, he’ll swipe a misbah without thinking twice.

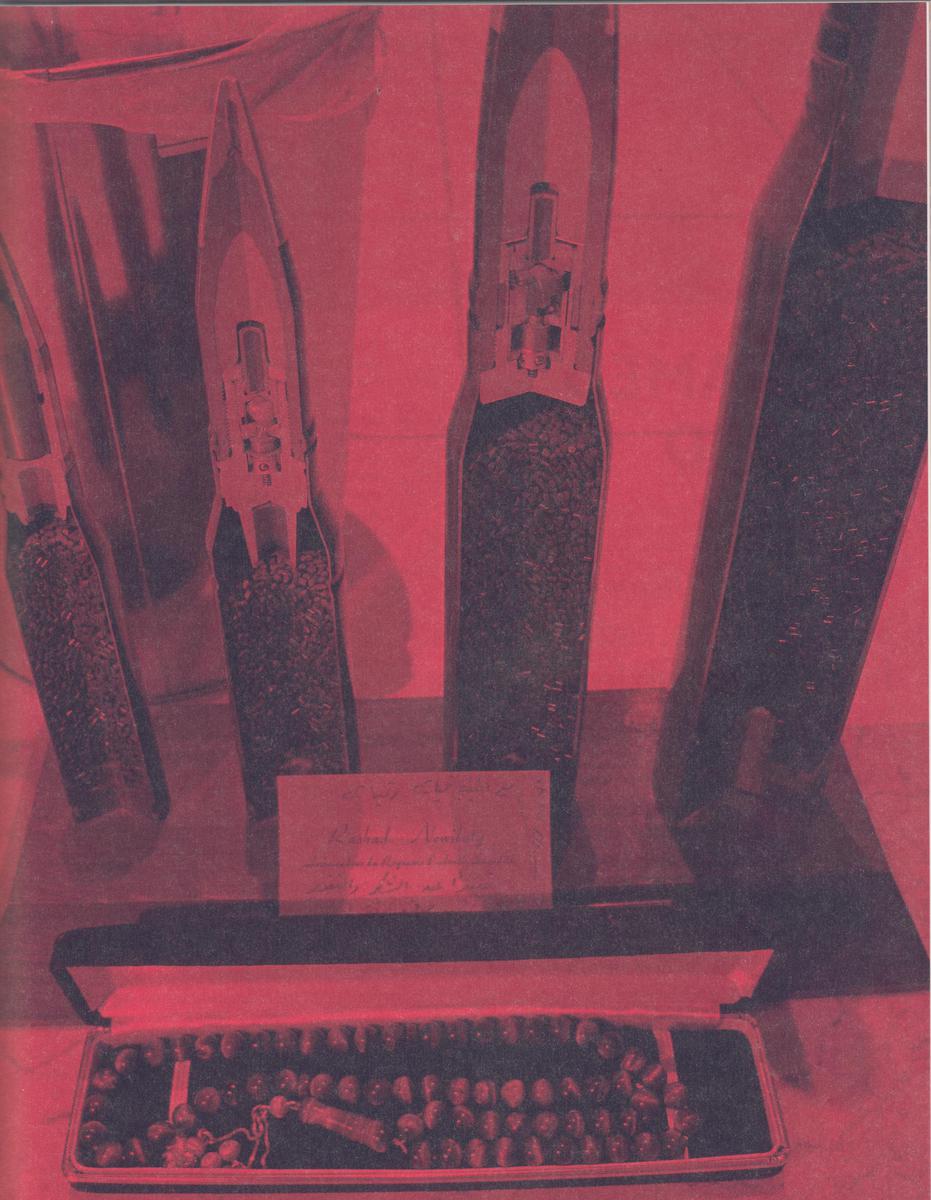

My father began stealing misabeeh as a young man in the early 1970s. Carefully unpacking his pirate’s booty one day, we counted a grand total of 177. They came in every color and size imaginable. Some were in beads of plastic; others wood, silver, or gold. Still others were turquoise, jade, ivory, pearl, malachite, black onyx. One was made of coffee beans. But most were made of kahram, a kind of yellowish amber that releases a faint scent of lemon when rubbed.

My father tells me that thieving is all about timing. He’s never been caught outright. A few times, a former owner has suspected my father and run after him; my dad denies the theft every time, of course. Sometimes the person will keep asking after his beads, regaling my father with stories about their sentimental meaning, until my father is overcome with guilt, pity, compassion, or annoyance, and gives them back. But this almost never happens — maybe a handful of times in four decades.

A good theft is “artistic,” according to my father. “Sometimes you have to get up, run off, put the misbah in your car, and dash back before anyone notices. So that when they ask to look in your pockets, they’re empty.” I asked him once if there had ever been a court case involving a stolen misbah. He’d never heard of one.

It seems that, though this practice isn’t universally loved, it’s nonetheless accepted. And even though it’s not common in the rest of the Gulf, if a Kuwaiti steals a misbah from someone in the region, it’s somehow okay; they respect it out of regional kinship.

Most all the misabeeh in my father’s collection are new. A couple are older, kept in cloth bags, broken beads worn down by the anxious hands of their former owners. But the turnaround on misabeeh is pretty high, so the thief ’s cache tends to be in mint condition. My father keeps them all in a duffle bag, which is locked in a safe in his room.

“Ninety-five percent of the former misbah owners have no clue that I am the thief. There’re a few men with a reputation for stealing misabeeh, but I keep a pretty low profile myself. Personally, I think my collection is moderate.

“What is the most valuable misbah I’ve stolen? The tiger’s eye stone misbah that I stole from the Saudi ambassador in Senegal in the early 1980s. It’s valued at a little over $3000. He figured it out pretty quickly, though. He actually sent me a little box with a note, officially gifting it to me. ‘Halal 3alek,’ as we say. ‘Halal on you.’ Meaning, ‘It’s all yours.’

“It was a rare feat to steal a misbah outside Kuwait.” My father smiles. “It’s a joy to steal misabeeh. Remember, as with all forms of theft, the most important thing is sleight of hand — in the pocket and bounce before they figure it out! One day soon, I want to put all of them in a big display case and invite everyone I’ve stolen from to look at their former misabeeh. That would make me happy.”