As a child in Tehran, the artist Shirin Sabahi took weekly painting classes not far from Park-e Laleh, or tulip park, in the sprawling city center. Many an afternoon, she would wander over to the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, a low-slung building complex in the modernist style that had been erected in Park-e Laleh in the last days of the Pahlavi monarchy. Whimsical quarter-circles protrude from the structure like eyes and ears. Inside, a spiraling ramp, a little like the Guggenheim’s in New York, culminates in a massive black rectangular sculpture. The sculpture, which is called Matter and Mind, was a creation of the Japanese artist Noriyuki Haraguchi. Exhibited at Documenta 6 in 1977, it had been snatched up that same year by Kamran Diba and David Galloway, the museum’s director and chief curator respectively, in time for the opening in October. Like Kanoon, the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children, where Sabahi once took painting classes, the Museum of Contemporary Art had been patronized by Queen Farah Diba as a centerpiece of the regime’s vast and various investments in culture during the 1960s and 70s. The museum is said to contain the most valuable collection of modern art outside of the west, and continues to generate widespread fascination.

One day, a young Sabahi lingered before Matter and Mind with a friend. As they approached its shiny surface, Sabahi insisted that the monolith was solid, made of glass. Her friend demurred. To prove her point, Sabahi threw a crumpled-up bus ticket at its surface. The paper promptly sank. As it happens, she was not the first museum visitor to treat Haraguchi’s work, which is composed of 1,217 gallons of thick black oil, as a wishing well. Like the colorful Calder mobile that hangs from the museum’s central atrium, or the shiny Donald Judd sculpture that sits impassively next to a fire hydrant, Haraguchi’s oil pool is nearly synonymous with the institution that hosts it. The pool, too, is an institution.

Two decades later, Sabahi sought out Haraguchi, now in his seventies and living in a house surrounded by rice fields in the Japanese prefecture of Iwate. She struggled to explain why she had traveled so far to see him. She wasn’t so sure herself.

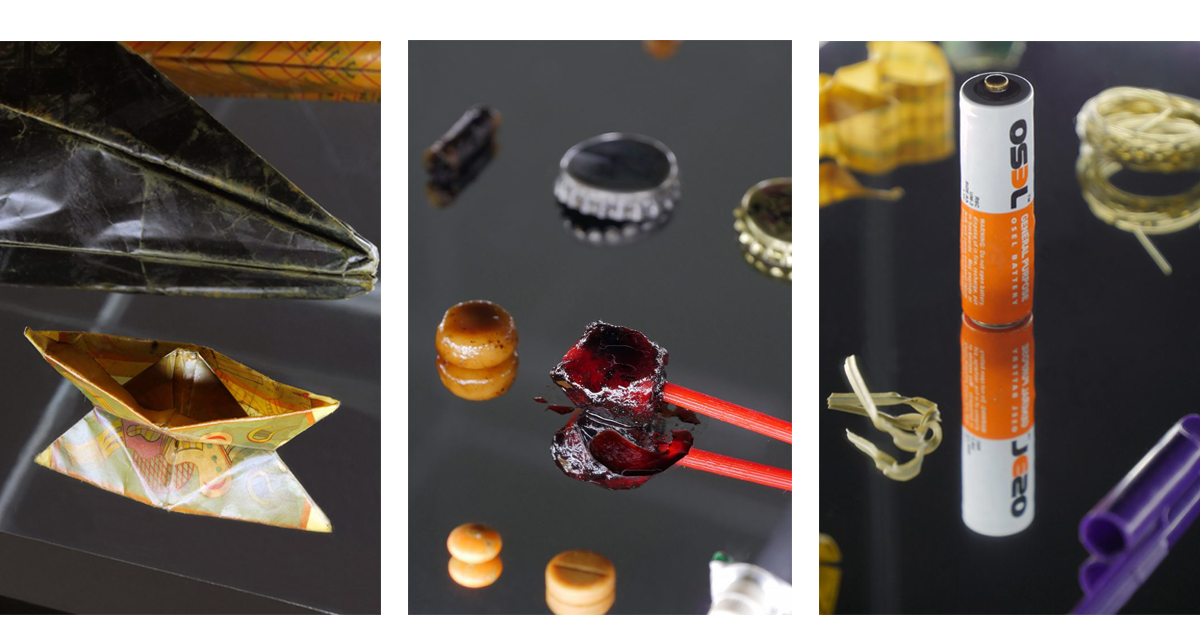

The clips we present here, excerpted from the larger works Mouthful (2018, 37’) and Borrowed Scenery (2017, 15’), depict Sabahi’s encounter with Haraguchi at his home in Japan; her coaxing him to return to Tehran to restore his iconic art work; and finally, the restoration itself — which entailed dredging up forty years’ worth of motley objects from the pool’s murky depths.

-Negar Azimi

>