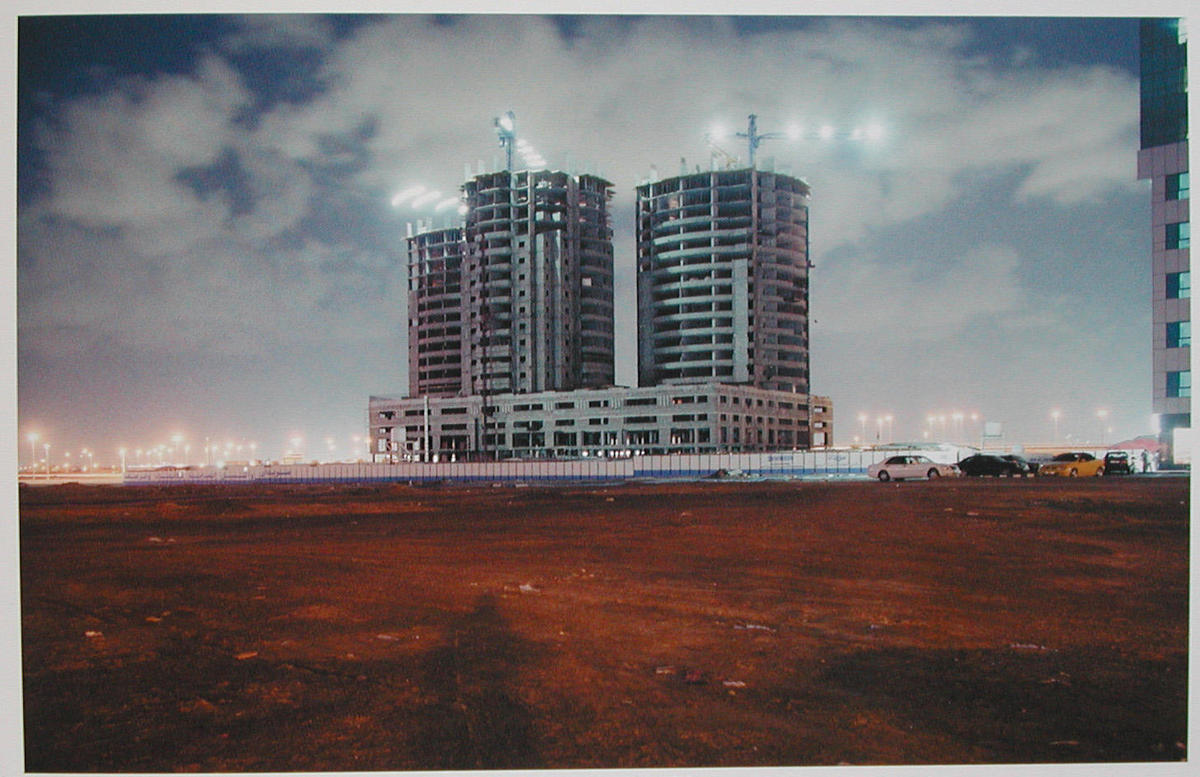

Sharjah

Sharjah Biennial 7: Belonging

Various venues

April 6–June 6, 2005

It would be outrageous to deny that setting, locale, atmosphere, and even one’s personal relationship to the artists all have a tremendous influence on the observer of contemporary art. In the case of a biennial, the impact of the environment is even more pronounced, since one isn’t dealing with a single work of art but a whole range of artworks in a variety of different spatial constellations, which can require hours, even days to take in.

Right from the very first day, my wife’s sister was constantly complaining about the triangular swimming pool in our Sharjah hotel. For me, this was not an issue; I actually find Sharjah an agreeable place, much more so than Venice, for example — where the hotels have no swimming pools at all (triangular or not), and the beaches are so polluted one wouldn’t even dream of going swimming. That aside, the climate in Sharjah is far more pleasant, people are friendlier, and the food is also better. (Allow me to recommend the Karachi Palace — you’ll recognize it by the bold slogan in red, “You’ve tried the rest, now try the best.” Even at 2 am, the Karachi will serve an excellent mango lassi — the kind of refreshment the Venice Harry’s Bar clientele can only dream of. A Karachi Palace mango lassi is delightful even after the third glass, very much unlike those gummy Bellini concoctions.)

Now, about the art. San Keller installed a very subtle and sensitive sound piece, Annunciations, which, as jury member Okwui Enwezor confessed to me later on in the Karachi, was actually so unobtrusive the festival jury failed to notice it altogether. Keller had asked all the artists and curators involved in the Biennial to provide him with what they thought were relevant passages from the canon of art history. He had these passages read from loudspeakers on the main square in front of the Sharjah Art Museum, four times per day. It was an elegant and highly memorable way to reveal the ideological leanings of the individual participants, and present visitors with the intellectual identity of the Biennial as a whole. Maybe the installation’s rather obvious reference to the muezzin tradition was lacking in subtlety, due to a typically superficial western attitude towards certain Middle Eastern icons. But “Annunciations” was successful in gently rubbing everyone’s nose in the Biennial’s ideological makeup.

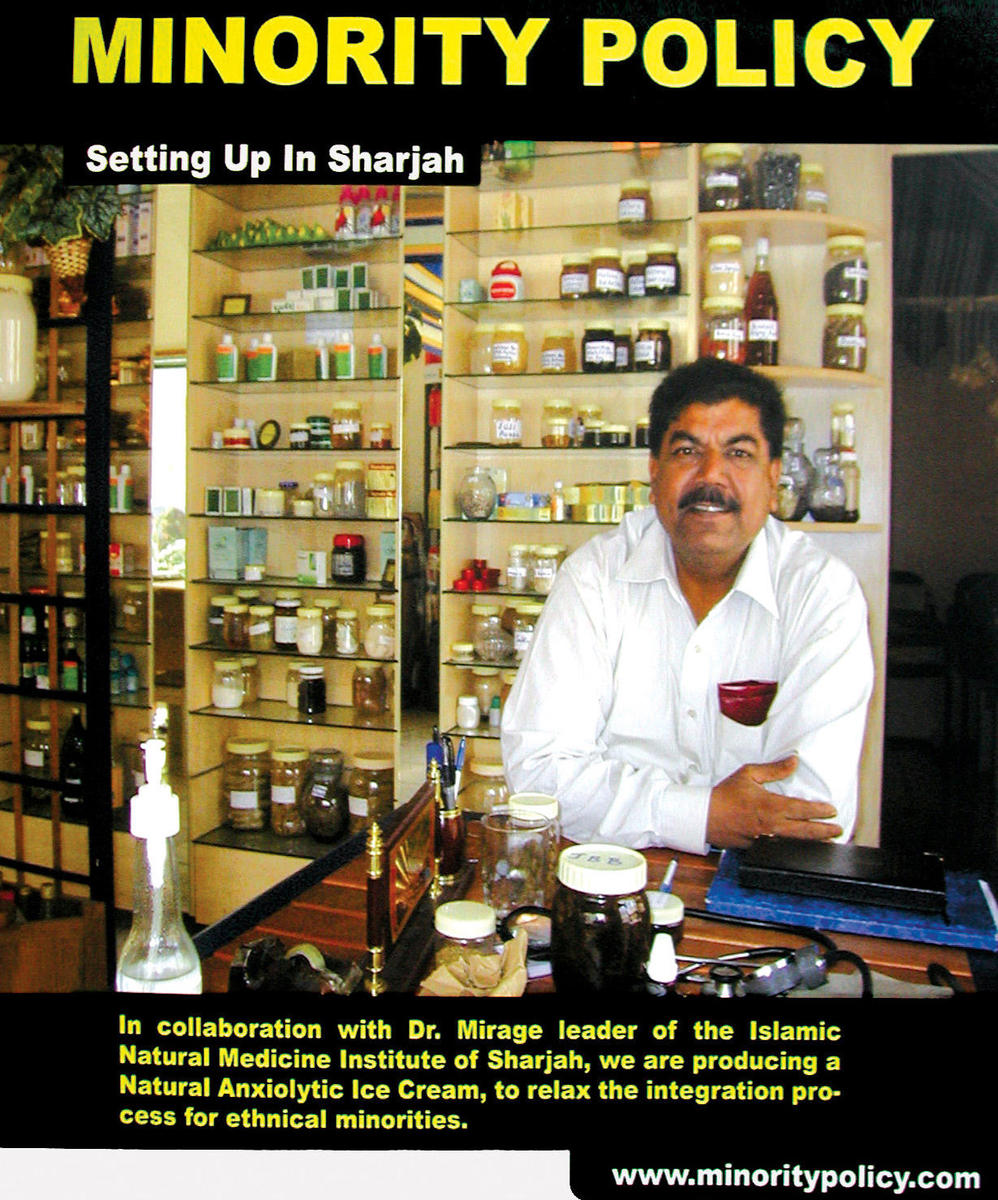

Far less attractive was Pio Diaz’s Setting Up in Sharjah, which also took place on the main square in front of the museum. (My negative reaction has absolutely nothing to do with the fact that the artist insulted and ridiculed me on several occasions in front of his peers. Although to a certain extent, his ill-mannered attitude does become manifest in his work.) Diaz’s project consisted of some sort of an ice cream parlor which served as advertising (or “bait,” as he put it), for a webpage minoritypolicy.com that disseminates useful information for Sharjah immigrants who would like to set up a business. It was certainly an interesting approach, but far too befuddled to be taken seriously. The intervention on the square soon proved to be nothing more than a swanky, pointless boast, for after the first day, not much was left of the parlor besides a cluttered little ruin of an ice cream shack. Such projects may make sense in Argentina, but in a place like Sharjah, it is patronizing toward the immigrant working classes, who are degraded to the status of guinea pigs.

The work of Christoph Büchel and Giovanni Carmine, on the other hand, was rather interesting. With their complex, beautifully designed installation PSYOP, the two young artists exposed the propaganda machinery of US imperialism, even representing it, as some have pointed out, as an allegory of the international art system. In the Sharjah Art Museum, they built a seminar room of the US Army’s Psychological Operations Unit, a simple space filled with desks and metal chairs. In the corner was a TV set playing a film once used in the late 60s to train occupying US troops in matters of psychological infiltration. “Win their minds,” it claimed, “and their hearts and souls will follow.” Stacks of cardboard boxes containing all the flyers dropped during the recent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were arranged along the walls of the classroom. A beautifully designed and meaningful work.

Mario Rizzi contributed a pompous and overblown work, Out of Place, that I must mention because I cannot believe the festival jury (which included Rina Caravajal and Walid Sadek as well as Enwezor) actually fell for this upsetting example of Proletkult. At the award ceremony, during which the artists Maja Bajevic and Moataz Nasr were also honored, I almost felt ashamed in front of the tasteful and soft-spoken patron of the event, His Highness Dr. Sheikh Sultan bin Mohammed Al Qasimi. By awarding Rizzi, the jury set a very bad precedent, since his work has little to offer other than bourgeois idealization of gypsy romanticism. I suspect that it received the award only because of its seductive style of presentation: a row of immense projections in a dark room, some moving film matter, some music, some politics. Usually does the trick.

In addition to her video piece, Emily Jacir produced a highly poetic work Embrace consisting of a circular luggage conveyor belt. The sculpture obviously points to the artist’s uprootedness (she is based in Ramallah and New York). One should concentrate on the work’s composition and entirely disregard its content and postcolonial emotionalism; it comes dangerously close to Rizzi’s video work in that respect. At the Karachi, I made a point of staying in the smaller room reserved exclusively for men whenever possible, in order to avoid any conversations with the artist, for that would have gravely threatened my personal enjoyment of her work in terms of its outstanding formal qualities.

I will end with a brief remark on the curators. In principle, we all appreciate the open-minded atmosphere of a place like Sharjah. But we do wonder how far these people want to go. Fortunately, there was at least one Muslim — Tirdad Zolghadr — among the team of curators (he is of course a Shia, but that is better than no Muslim at all). My wife’s sister maintained that Zolghadr was also the best-dressed among the curators, which is entirely untrue from my perspective; she has simply been living in Ankara for far too long. But Zolghadr was unfortunately the most arrogant of the three curators, boasting to the local press that he would “make Venice look like an afternoon bake-a-cake contest.” Nice try.