Montreal

Sorry, Out Of Gas

Canadian Centre for Architecture

November 7, 2007–April 20, 2008

In 1973, the Livelihood Club Consumer’s Cooperative was holding one of its regular meetings in a living room in downtown Tokyo. The Livelihood Club was and is an organization of radical housewives (including, notably, my mother) founded in the late 1960s to foster alternatives to consumerism; the name translates from seikatsu-sha, “one who is engaged in living.” Like everyone else in the Japan, co-op members were talking about OPEC, the oil embargo, and its devastating impact on the nation’s economy. Then as now, Japan was completely reliant on foreign oil, and the country was in crisis mode, rationing consumer goods and bracing for runaway inflation. At one point during the meeting, an errant guest opened a closet door while looking for the bathroom, unleashing an avalanche of stockpiled toilet paper. The assembled ladies gasped in disbelief, shocked by the hoarder’s bad faith. Today the Livelihood Club maintains a bank, a political party, and a network of cooperative stores, but people still talk about that meeting and the “toilet paper affair.” They also, more fondly, recall the local politician who drove around the district during darkest days, dispensing black-market toilet paper from the back of his pickup truck.

Scarcity was the looming backdrop of ‘Sorry, Out of Gas,’ an ambitious exhibition at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal. The problem was posted in the central room, where looping interviews of global leaders addressing an apprehensive world testified that Tokyo housewives were not the only ones in a frenzy. There was Richard Nixon, urging his public to turn the thermostat down to 68 degrees, while the Saudi oil minister Sheikh Ahmed zaki Yamani, a trace of a smile on his lips, said, yes, the price hike did imply an adjustment of the world’s power structure. Yet the oil crisis of 1973, triggered by OPEC’s price fixing, was artificial. Thirty-five years later, the energy crisis is real, compounded by climate change and environmental devastation. Today, as various sectors attempt to consider greener alternatives to deal with the “inconvenient truth,” the CCA show proposed a reconsideration of the last crisis and the spasm of creative responses to it. Curator Mirko zardini aimed to provoke today’s architects by showcasing the example set by their 1970s counterparts: the architect as an innovator and renegade.

Organized into four groups — Sun, Earth, Wind, and Integrated Systems — each room contained research conducted in apparent isolation. But there was more to link the work than the faceted black display case that contorted its way from room to room: there was the willingness to work free from the debates and styles of the day, the enthusiasm for forging a new style based on experiment and discovery.

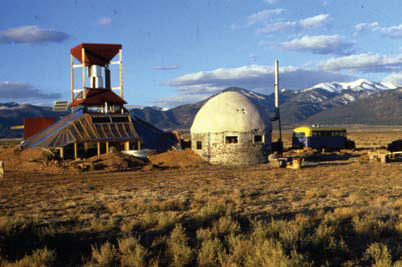

Many of the experiments in 1970s sustainable housing were the work of hobbyists, hippies, and engineers rather than trained architects. Michael Reynolds created “earthships” out of recycled tires and empty beer cans to great textural and light effect, while Steve Baer used aluminum pie tins to create cheap and powerful forms of insulation. Of course, one reason today’s architects tend to resist green technology is precisely the stereotypical images of giant roofs clad in photovoltaic panels and inclined toward the sun. President Jimmy Carter, an engineer himself, installed solar paneling on the White House; Ronald Reagan, upon taking office, had it removed, and few protested.

Another common approach in the 70s and 80s was to berm or bury the building. Architect Mark Mack proposed buildings that could be pulled out of hillsides like kitchen cupboards. In addition to providing natural insulation, building underground allowed designers to sidestep the question of style that had bedeviled the solar architects. Their underground interiors gave them away, however, for many were caricatures of their aboveground counterparts, with photographs of natural scenery taped on the walls to mimic the view from windows. In one design, families stood smiling around a barbecue grill, white picket fence and blue sky painted on the wall, a giant ventilation shaft towering above them.

The perfect home to satisfy every constituency is, of course, a fiction. But while every practitioner was preoccupied with technology, none of them believed it would be enough to solve the problem of scarcity. Not only would you be living in a different kind of house in the future, you would be living differently.

Perhaps the most useful role models for today’s architects could be found in the Integrated Systems room. These groups of thinkers and practitioners conceptualized energy not as a discrete issue or sum but as part of a system, and devised solutions integral to various human necessities. The New Alchemists in particular stood out for their rigorous approach toward living itself as an experiment. Working out of a former dairy farm on Cape Cod, they recorded every worm they found on cabbages, every cabbage they fed to rabbits, and every tilapia that fed on worms and created windmills to pump water into the pools where the tilapia lived. The purpose of their investigations was to find comprehensive answers to the problems of scarcity and sustainability.

How should today’s architects deal with the unanswered questions of 1973? It’s not immediately clear; one obvious direction would be to build less, possibly eliminating the architectural profession as we know it. On one side of the architectural spectrum is Rem Koolhaas, who seems to believe that Armageddon is coming, anyway — so why not dream great dreams, build big, and die beautiful? But those architects who are engaged in building for living confront a different kind of heroic task, as we continue to reexamine our relationships to cities and to nature. ‘Sorry, Out of Gas’ reminded us of the stakes, while also suggesting that a house built out of Schlitz cans might be genius and that stocking twenty thousand tilapia in your pond because they’re the easiest fish to herd is magical thinking of the best kind.