Beirut

Home Works 5

Various venues

April 21–May 1, 2010

Christine Tohme, one of the five founding members of the Beirut-based arts association Ashkal Alwan, has been dodging wars, invasions, occupations, and insurrections for a decade now. The Home Works Forum on cultural practices is her signature event, a juggernaut of exhibitions, performances, film and video screenings, lectures, panel discussions, and artists’ talks that has occurred five times since 2002, often sidestepping political upheaval to generate a great deal of artistic urgency and intellectual intensity.

The first edition of Home Works coincided with the outbreak of the second Palestinian Intifada in 2002. The second edition was delayed six months because of the US-led invasion of Iraq; the third was derailed for six months when Lebanon’s former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri was killed in a massive car bomb blast in early 2005. The fourth was scuttled twice, first due to the Israeli bombardment and siege in the summer of 2006, then to avoid coinciding with a particularly troublesome round of parliamentary elections, which at the time seemed likely to ignite sectarian strife.

In a text from 2005, Tohme wrote: “At this point, the Home Works Forum has (we think) settled into a regular schedule of regular disruption. This unpredictable dynamic has become a rhythm, a paradoxical routine. Because the practical and political circumstances around our work are always breaking and shifting … questions about dislocation and disruption have imposed themselves repeatedly.”

The biggest threat to this year’s edition, which ran from April 21 through May 1, was, for a change, meteorological — the Icelandic volcanic ash that grounded planes and closed airports across Europe for a week in April. Tohme, to her credit, managed to get to the city, on time, almost all of the participating artists, writers, and thinkers who weren’t already in or near Beirut. (A performance by the flamenco dancer Israel Galván, originally scheduled for the opening night, was swiftly reconceived as the event’s grand finale on Sunday.) But the crush of international curators, critics, collectors, board members, patrons, trustees, mid-level museum personnel, random academics, art world players, and the minions always trotting along behind them, was considerably thinned by the eruption of a distant mountain with an unpronounceable name.

Now that all is said and done — nine performances, seven discussions, eleven lectures, four artists’ talks, two walking tours, a museum visit, ten screenings, a six-hour colloquium, two exhibition venues, four theaters, one gorgeous architectural wreck, and a crypt underneath a church — it might also be worth asking whether or not Home Works 5 would have been better off had the dust taken a few more days or weeks to settle.

It was by far the largest and most ambitious iteration of the forum to date. Previous editions converged around loose sets of ideas — alienation and individuality in the age of globalization, in 2003; narrative and representation, in 2005; sex, catastrophe, and desire, in 2007 — that emerged from the works themselves, and wound around one another like delicate curatorial gestures following closely related threads.

For Home Works 5, however, Ashkal Alwan laid down five explicit themes ranging from education and sound experimentation to the regional impact of Abu Dhabi’s plans for Saadiyat Island. The themes were publicly announced, and proposals materialized in response. The result was a program both incoherent and over-stuffed, to the extent that by the end of it, most people attending the forum looked, and no doubt felt, as if they had been run over by a truck. As with any sprawling international art event, Home Works 5 included a number of excellent, rigorous, and rewarding works — amongst a lot of meaningless prattle and filler and networking.

One of the stronger pieces in this sprawling program was Photo-Romance (2009), the latest performance by the artists Lina Saneh and Rabih Mroué, which spliced politics and poetics into the conventions of Italian neorealist cinema and was the couple’s most overtly theatrical work in years. For the duration of the ninety-minute piece, Mroué and Saneh arranged themselves around office furniture placed on the right side of the stage, negotiating the script of a film that was periodically projected onto a huge screen beside them. The guitarist Charbel Haber, meanwhile, provided live musical accompaniment and the occasional interjection from a perch on the left.

The film onscreen was an animation comprised entirely of black and white photographs that told the story of two neighbors, a divorced housewife and a disillusioned left-wing journalist, who meet on a day when everyone else around them is attending political demonstrations. Highly crafted and intriguing in its ability to cut across different genres, styles, and ideas, Photo-Romance might not have been the most magnificent work the pair has ever done — so far that would be Who’s Afraid of Representation? (2004) — but it did show them still reaching for the edges of their discipline, searching for new possibilities and meaning in the situation of bodies on a stage.

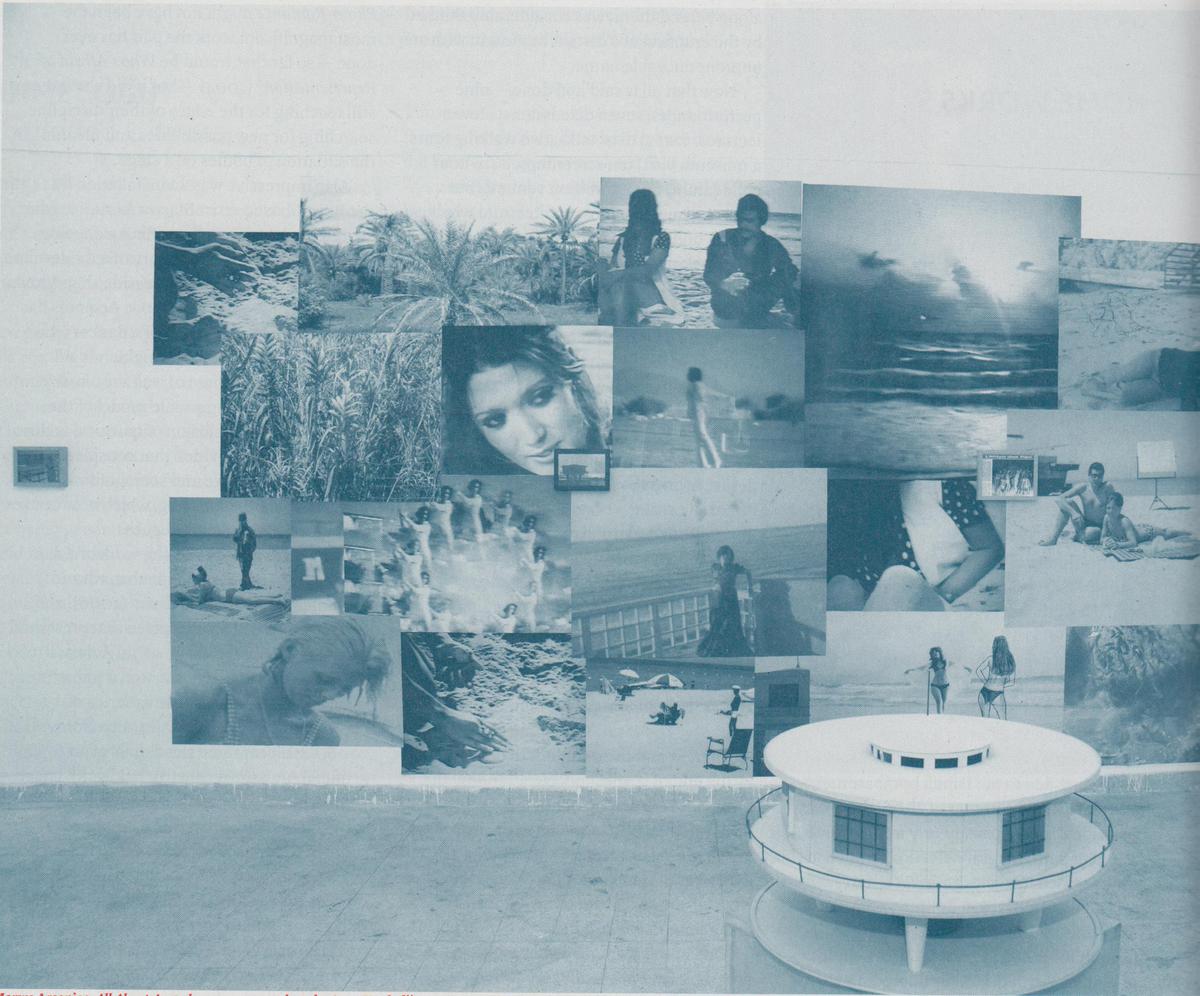

Also impressive was an installation by the Beirut-based artist Marwa Arsanios, who shared her latest installment in an ongoing project digging into the history of a modernist beach house located in the seaside shantytown of Ouzai. For several years now, Arsanios has been looking into the story of a dancer who disappeared from a nearby nightclub. All About Acapulco (2009–10) was a room-size installation featuring a scale model of the beach house, an explosion of quizzical archival photographs, and a video that considered the unusual narrative and sociopolitical significance of the building, which now houses a family of Palestinian refugees.

Another highlight was the work of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, who presented the video Mini Israel (2006), a strange and darkly comic piece that presented a theme park built outside of Tel Aviv as a utopian vision of the country on a miniature scale, alongside a provocative series of photographs entitled Chicago, also from 2006, which captured the details of an artificial Arab town constructed by the Israeli Defense Forces for tests of their military campaigns. The photographs amplified some of the weirder details of the site, such as the obsessively reconstructed explosive devices that clearly had no purpose in terms of training, and the posters used for target practice, at least one of which appeared to have been pulled from a blaxploitation film, raising questions about the role of racial and sexual stereotypes in military training.

During the forum, Broomberg and Chanarin gave a refreshingly raw talk about their work; it was the only such talk directly related to the works on view. A few members of the audience took them to task, intimating that their work was too beautiful, too aestheticized, not critical enough. Broomberg responded, in a way, by saying that their intended audience was a little bigger than the room hosting their talk. That room was Planet Home Works, a kind of bubble populated almost exclusively by people participating in the event and speaking a language of common references and recycled ideas.

That bubble-effect might be normal enough for the kind of pop-up events typical of the art world. But Home Works has in the past been a space both intimate and urgent, which people have come to cherish, rely on, and feel ownership toward, a territory carved out for the articulation of concerns that often fall outside mainstream politics and the international art scene. It was strange, then, to be in a space that seemed both so replicable — at times it could have been anywhere — and so isolated.

The thing is, Home Works was never meant to be the kind of event it may now have become. When Ashkal Alwan began in 1994, its mandate was to engage the city and activate a critical art practice capable of tackling social, economic, and political issues that were inextricably linked to the experience of Beirut and its relationship to the region and the world. Home Works grew out of a series of public art projects organized by Ashkal Alwan that made ample use of the gardens of Sioufi and Sanayeh, the Corniche and the once grand cosmopolitan causeway of Hamra Street, investigating their potential. Home Works was an alternative to big-budget biennials and splashy arts festivals well before either of those models was even plausible in a place like Beirut. For better or worse, in its fifth incarnation, Home Works became the very thing it never needed or wanted to be: a power summit, an occasion for lavish lunches and dinners and after-parties, an event with little to no local audience or consequence, which rolls into town, makes a lot of noise, blows a lot of hot air, then disappears.

Take, for example, the panel discussion on the relationship between Saadiyat Island and cities such as Beirut, Ramallah, and Cairo, which barely skimmed the surface of the subject. It was great to hear Vasif Kortun, the founding director of the Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center in Istanbul, finally air in public the story of how the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi engaged five curators — William Wells from the Townhouse Gallery of Contemporary Art in Cairo, Bayan Kanoo of Al Riwaq in Bahrain, Jack Persekian of the Sharjah Art Foundation, Christine Tohme, and Kortun himself — in an ambitious joint initiative, involving a major archive and research and programs shifting back and forth between institutions; that initiative has all but fallen apart. “Interest waned,” said Kortun, “and our proposal expired.”

Also on that panel, the curator-cum-novelist Shumon Basar enlightened and entertained with a performance that tried to pry open Abu Dhabi’s motive for creating a cultural district from scratch. The Emirati writer and commentator Mishaal Al Gergawi, in the meantime, offered a frank articulation of the logic of the Gulf: “I can come here, walk around Solidere, buy some art, and leave. What can you do for me? Home Works? Big deal. I can call Ashkal Alwan later, and I can talk to Christine, and I can ask her to do Home Works in Dubai or Abu Dhabi. Of course, she’ll refuse. But then I can find someone who’s left Ashkal Alwan, and we’ll do something close. We’ll call it, I don’t know, House Works instead of Home Works. I can make it happen.” A pause. “It’s ridiculous to use the Guggenheim to develop relationships.” For one thing, relationships among cities in the region existed long before the Guggenheim came on the scene.

But overall, the panel, so hotly anticipated, so heavily attended by culture brokers from the Gulf who made no more than a weekend of it, failed to go anywhere very interesting. It seemed at least half of the audience, coming from corners of the globe apparently not yet bored with Dubai-bashing, just wanted to hear the UAE described onstage as authoritarian, totalitarian, or autocratic, as statements of fact — which suggested that the level of discourse around Saadiyat is still lingering rather low (a situation not helped by the fact that the authorities involved in Saadiyat release so little concrete information, leaving a vacuum that speculation and conjecture will always gladly fill). Moreover, the panel itself was the feint of the artist Walid Raad, a mechanism for generating material for an artwork as part of his ongoing project on the history of modern and contemporary art in the Arab world; the notion of pursuing a genuine public debate seemed like something of an afterthought.

In his introduction to the panel, Raad said he hoped the discussion would both consider and produce new facts on the ground — political, social, economic, and aesthetic facts. But the ensuing conversation seemed more symptomatic than diagnostic. Has Home Works grown so big, and so art world, because the art scenes in the region are changing, becoming more professionalized or institutionalized? Has Gulf money done more harm than good? Are international institutions, by swooping in so aggressively, doing real damage to the delicate ecosystems of those scenes? Was it naive to think that the internationals had something to learn from the experiences of, say, Beirut, Cairo, Istanbul, Amman, or Alexandria, where small-scale initiatives like Ashkal Alwan, the Townhouse Gallery, Platform, Makan, and the Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum, among many others, have been nimble and experimental and occasionally haphazard in creating their own, sometimes marvelous, sometimes tragically incompetent, modes of production and distribution that, regardless, give artists room to breathe, to live and work and think, free from the pressures of the market and the dismal, managerial politics that make large-scale institutions in London or New York such a bore and so bureaucratically cumbersome? At the tail end of the panel discussion, the artists Hassan Khan and Oraib Toukan raised some of these questions in quick, forceful bursts, but there was no time to take up their comments.

It should be noted that Home Works 5 marked a major turning point in the history of Ashkal Alwan, making official the news that Tohme and Co. are opening an art school and a permanent exhibition venue in the fall of this year. Two months ago, l’Association Philippe Jabre gave Ashkal Alwan two floors in an old, rust-colored furniture factory in Jisr al Wati, an industrial district on the eastern edge of Beirut, rent-free for the first five years. What began in 1994 as a highly improvised, hyper-flexible initiative, without so much as an office, is now set to become a solid, sited institution with a pedagogical mission.

One of forum’s five themes was “In and Out of Education…What Can We Teach Nowadays?” None of the three panels addressing that question yielded much of an answer, which doesn’t bode well for the Home Works Academy, if indeed the forum was intended to be a place for testing out new ideas about what an art school in Beirut could be (never mind the fact that, despite the participation of a few local professors, the panels proceeded as if the Arab world were a wasteland with no existing art schools, faculties, or departments). What those panels did do was indulge in a lot of art world jargon, verbiage, and abstraction. If that passes for education, and if Ashkal Alwan’s art school ends up importing the worst and most tedious excesses of art schools elsewhere, then an alternative to the alternative that was Home Works might now be sorely needed.