London

Hashem El Madani: Mediterranean

The Photographers’ Gallery

October 14–November 28, 2004

A successful portrait photograph often reveals what the sitter actually wants to think of him or herself. August Sander’s early twentieth-century mission to document the population of Germany, for instance, might now seem unthinkably grand and simplistic, but a cursory look again at his photographs reminds us how full and revealing the representation of the steady gaze can be. Having photographed the residents of Saida for the past fifty years, Hashem El Madani has amassed a collection of over 75,000 images representing around ninety percent of the population of that city in the south of Lebanon. This project — on show for the first time outside Lebanon — may not have originated out of Sander’s lofty ideals, but makes for an exhibition that is equally revealing nonetheless.

Think how much people use photographs to instantly portray what they are, what they do; we live in a more immediately retrospective time than ever, using our mobile phone cameras to document even the most apparently meaningless moments. This exhibition shows the universal need people have to construct themselves. Madani seems to be the most selfless of photographers; he insists that photography is a service profession and that a portrait must render its subject beautiful, reducing full-faced people with a sharper angle, allowing crossed eyes to be either retouched or at least hidden. This is not about lies; it is in fact about the “truth” that people want to present about each other, to each other.

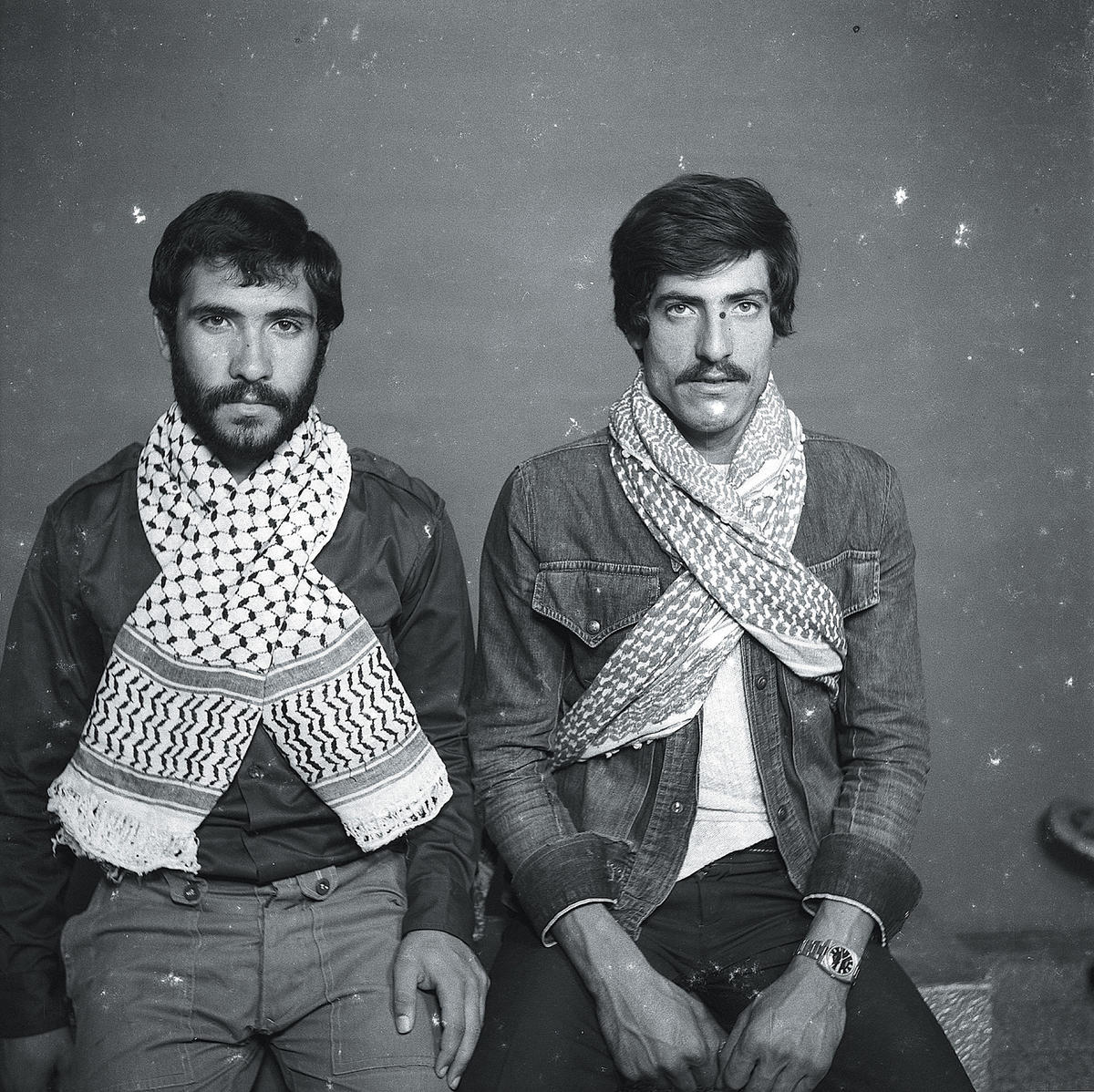

With their scarves wrapped in a cross under their armpits, the resistance fighters stare out directly at the camera. Madani offers an explanation, as he does about all of the work: “These are Syrians… . They used to come unarmed to the studio.” He began taking photographs of the population of Saida in the 1940s. Perhaps the high point came in the 1960s and 1970s, and after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, business started to decline. Madani worked to produce imagery that was acceptable in every way to the sitter, the parent, the lover; he would cover every conceivable physical blemish and sacrifice the useless image of truth in the production of an elaborate facade. How fascinating to go right back to the surface of a photograph, with the negative scratched and doctored, to remove an unwanted, unmentionable ex-wife! Madani would retouch work by other photographers, as well, to remove the occasional crossed eye, for instance. Girls kissing, boys hugging, a loss, new love, good friendship are all conveyed with equal attention, intensity and purpose.

Probably the most unusual aspect of the exhibition is that this mass of imagery is accompanied by a series of accounts written by the photographer. The retrospective nature of this signifies that he is commenting and explaining in the present about something in the past: it would be difficult to see, concentrate, and understand otherwise. Here, a practical characterization of a set time and state can combine with light touch to reveal how functional the work is; in any other circumstance it would not be at all desirable for such a level of narrative, such anecdotal account, but this works in a different way. Time is held still but also consciously revived and commented upon.

The mass of work means that patterns evolve quickly, and gaining a knowledge of the general project makes concentrating on the particular individual very difficult. The runs of images include a young women holding the back of a chair; naked boy babies on a sheep skin rug; women and children touching the dial of the studio radio; Palestinian “resistance fighters” with their guns; young girls standing around a table with table cloth; a Palestinian girl writing a letter to her lover. All start to produce slight shifts in pose and a movement across the surface — with the radio here, the radio there, the pattern of the table cloth, or a jauntily set hat. The unconscious nature of constructed imagery seems to speak back and create its own rhythm.

Madani’s atelier in the Chehrazade building, which he opened in 1948, was one of the first functioning “drop-in” photographic studios in Saida. Madani worked here, in his parents’ home, and in the homes of families. With such an equal dose of fiction and fact inherent in the nature of the work, the actual place where the photograph is taken is of little significance. To Madani, it matters much more that the place be accessible. He describes his studio as perfect, as “appropriately discreet, large, and inexpensive”; women could come in and leave unobserved, and his clients could pop in over and over again, often late at night, after having seen a movie, for instance.

The exhibition, part of the Photographers’ Gallery’s Mediterranean season, was jointly organized by Akram Zaatari of the Fondation Arabe pour l'Image and British curator Lisa Le Feuvre. Madani’s collective portrait of a particular society over half a century exemplifies the interdependent, close relationship between imagery and desire.