Serial Cases, a collaborative video project organized by ten international curators, aimed to highlight the parallel histories of artists in Middle Eastern and European countries. The project was presented in eight cities between November 2005 and March 2006 www.nomad-tv.net/serial_cases. Israeli curator Eyal Danon’s contribution, Trespassing, featured films and artists’ videos documenting projects, performances, and happenings in Israel and Palestine.

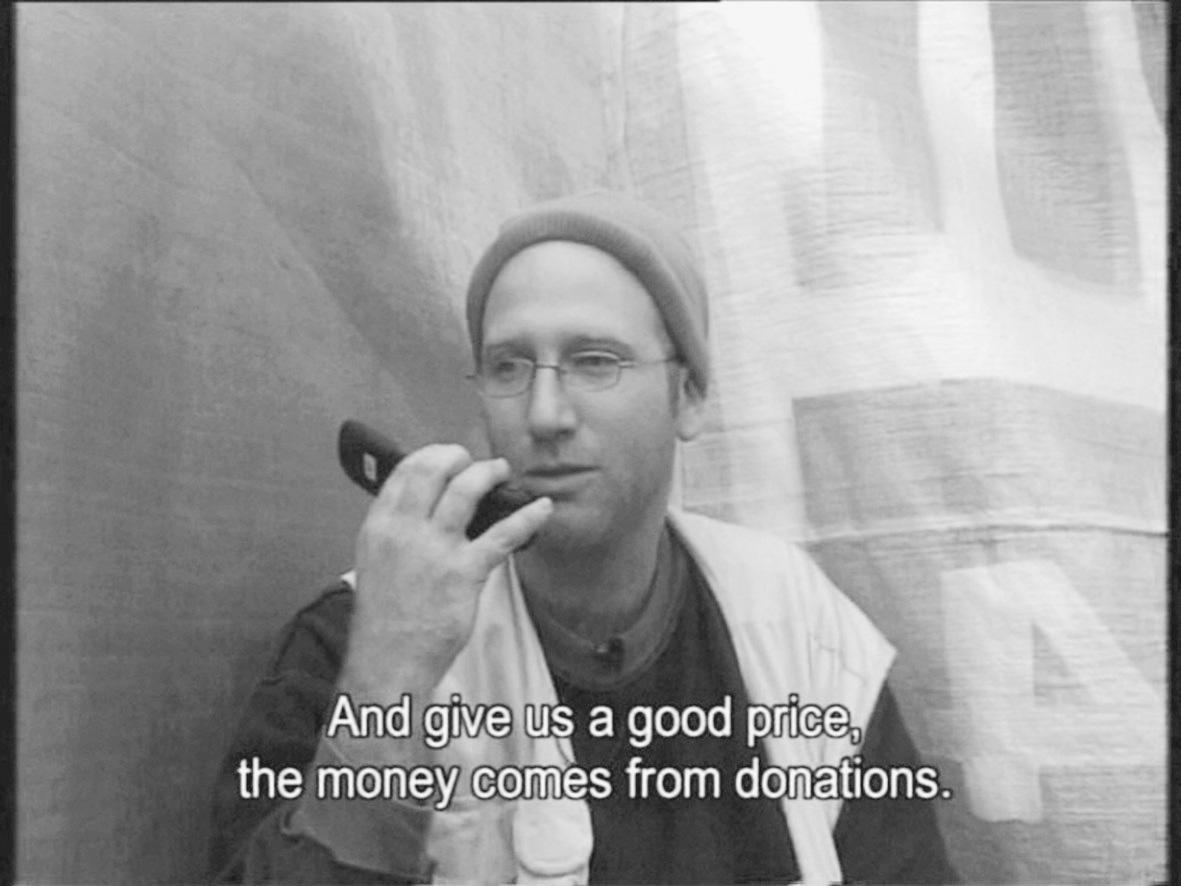

Palestinian/Israeli group Artists Without Walls, for example, set up two video cameras positioned at the same spot on either side of Israel’s “Separation Wall” in the Palestinian village of Abu Dis. The cameras were connected to two video projectors, each one projecting the image on the opposite side in real time, creating a virtual window and allowing people on both sides to see each other. Annan Tzukerman’s Anxious Escapism is a personal video about the artist’s struggle to be embraced by settler society. In the course of the journey, he transforms into a wild settler, in fact “crossing the lines” between himself and his hosts. Ruti Sela and Ma’ayan Amir furthered their exploration of young Israeli society with a film about online dating services. Trespassing also included films and video projects by Avi Mograbi, Clil Nadav, and Nira Pereg.

Basak Senova, one of the curators involved in Serial Cases, talked to Eyal Danon about the concept and act of trespassing. Danon noted that “the selection shows works by Israeli artists who themselves commit the act of trespassing. This act can be physical or mental. However, it implies more than a simple act of changing sides and loyalties: they trespass the unseen but profoundly existent borders of ethnicity and professionalism, despite political and social pressures.”

Basak Senova: The act of “trespassing” takes on different implications during the stages of actualization, representation, and dissemination of the works. In most of the selected works, when the trespasser commits the act of trespassing, he himself becomes threatened by anyone communicating or interacting with him. This very act also embodies the basic paranoia regarding the anarchic nature of the forbidden zone. Who is the intended recipient of these acts of trespassing?

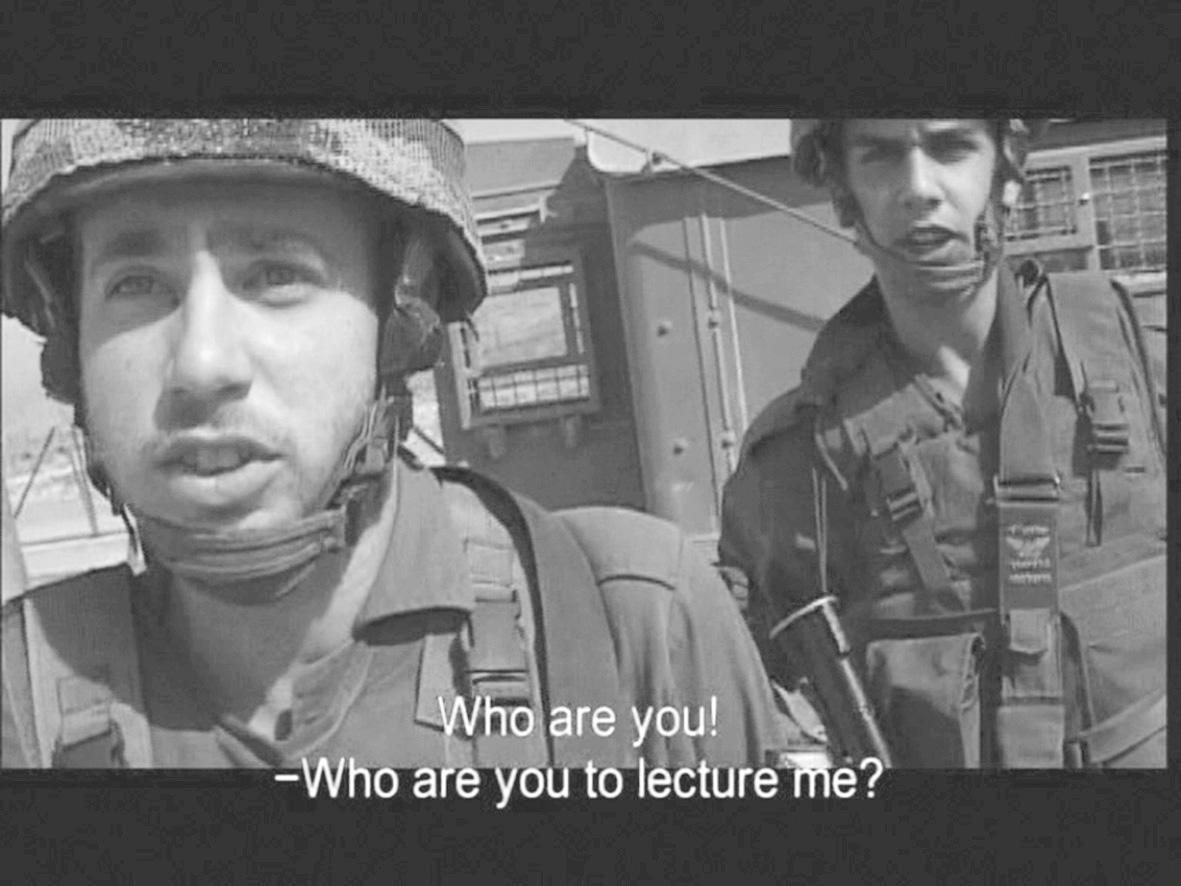

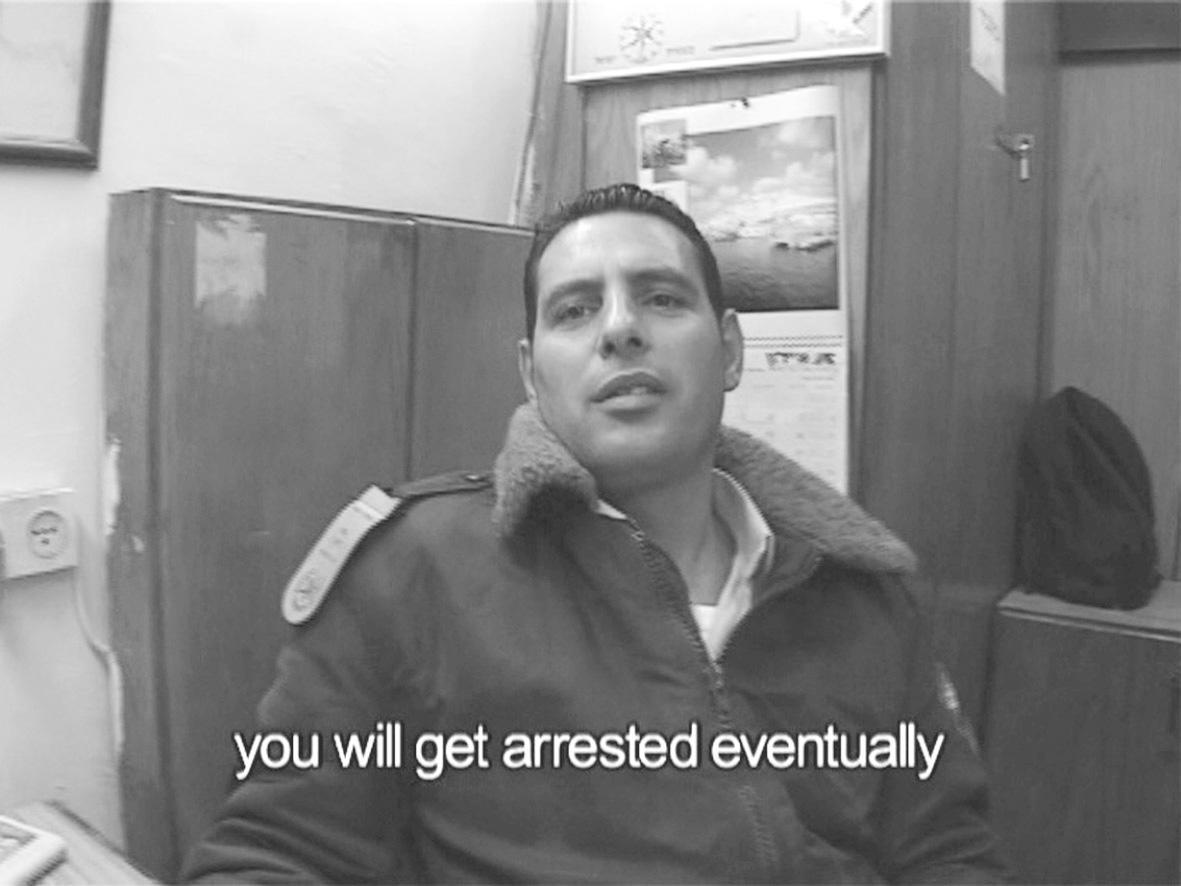

Eyal Danon: There is no difference in the act of trespassing as executed by an artist or any other citizen. Because all systems of control and surveillance monitor the environment to trace and eliminate any act of trespassing, it’s obvious that in these cases the artist becomes part of the paranoia, and is the living proof for the necessity of the system he or she tries to oppose. However, the artist stays on the border, making the act of trespassing a continuous rather than a momentary action. The continuity of the act is a privilege only the artist can have, being still on the “side” of the system, from the same ethnical, national, gender group. It differentiates him or her from the regular “clients” of the system who would not be treated with the same tolerance. So the intended recipients are the people — soldiers, settlers, Palestinians, pupils, police — who are in direct contact with the artists during the act, and also the future audience. However, the important thing is not the appreciation of the act, but its realization. By being simultaneously in and out of the system, the artist turns the act of trespassing into a tool through which the audience can both view and question the structure being criticized.

BS: Throughout your selection, the artist’s interaction with the political situation and its control mechanisms is indicated by physical objects (high concrete walls, checkpoints, mechanical surveillance systems), by the executors of regulation (the authorities, soldiers, settlers) or by illustrated mental blocks. These control mechanisms (operating on physical, physiological, social, political,territorial,and military levels) must have already defined clichéd identities [of Palestinians/Israelis] in order to cognitively map the region. Do you see any danger that artists and their purported activist acts could paradoxically serve the system through fulfilling these identity roles and normalizing these reactions?

ED: The extremely high usage of such mechanisms stands in complete contrast to the extreme absence of any public debate about their necessity, price and influence on Israeli society. It’s true that endless excuses can be found for any type of implemented security mechanism, but that this implementation can go through without any questioning indicates the fact that the Israeli public has willingly given up some of its freedom and civic obligation to the military system in exchange for the feeling of security. This exchange gives almost endless power to the army, exarmy,and all other kinds of security experts.

The fact that the action has so little public echo enables it to function without being a direct threat to the system, without being yet another excuse for more security mechanisms. At the same time, it does have an effect on the audience, a minor effect, maybe not wider than the borders of the art scene. But this effect is important since the information and debate is missing within the art scene as in any other part of Israeli society.

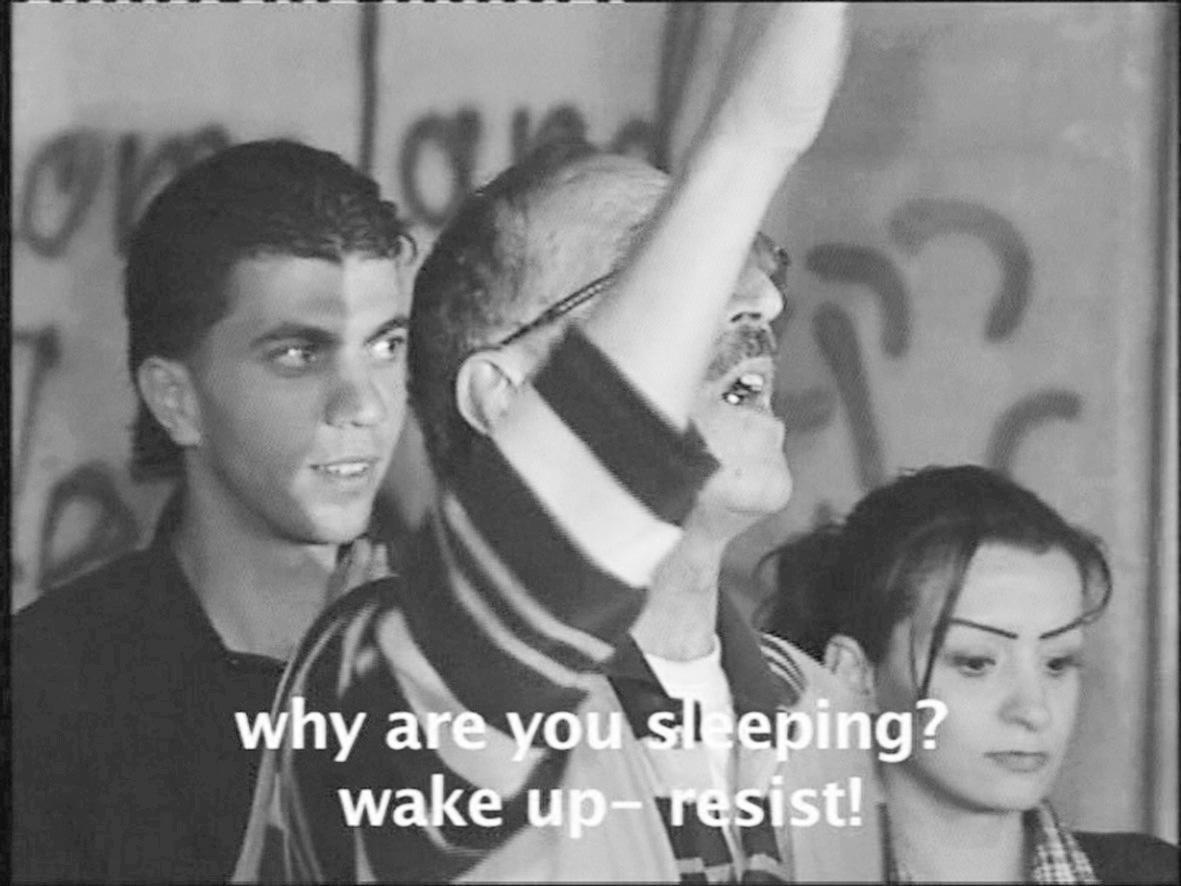

BS: In the selection, Avi Mograbi violently resists the authorities: his work Details 3 and 4 views two corresponding scenes filmed in the Occupied Territories. The first one documents soldiers attacking him, while in the second, he attacks them. Annan Tzukerman subtly depicts his attempts to be embraced by a settlement community. What is the social and psychological significance of these works in terms of mobilizing fear?

ED: I don’t think it is a coincidence that during the last two or three years, when these works and actions were taking place,some other processes that never quite got much public attention and influence occurred eighteen-year-old men refusing to serve in the army, pilots refusing to bomb in the occupied territories, women’s organizations monitoring the behavior of soldiers at checkpoints, and more. Now, the increased attention the wall gets from international artists as well as other groups of activists brings to the surface a diversity of motivations and interests, most of which are not very relevant or influential to the people directly harmed by the wall. The wall is such a magnet of interest because it became the essence of the conflict. The complexity of the Palestinian-Israeli struggle has always coiled outside spectators as it went through various filters of the mass media, so the presence of such a clear and stable symbol attracts all the attention and efforts. Therefore, in many ways, the wall serves as a canvas that different motivations and intentions can cover.

BS: To what extent does the content and discourse of these art-related projects differ from that of the mass media?

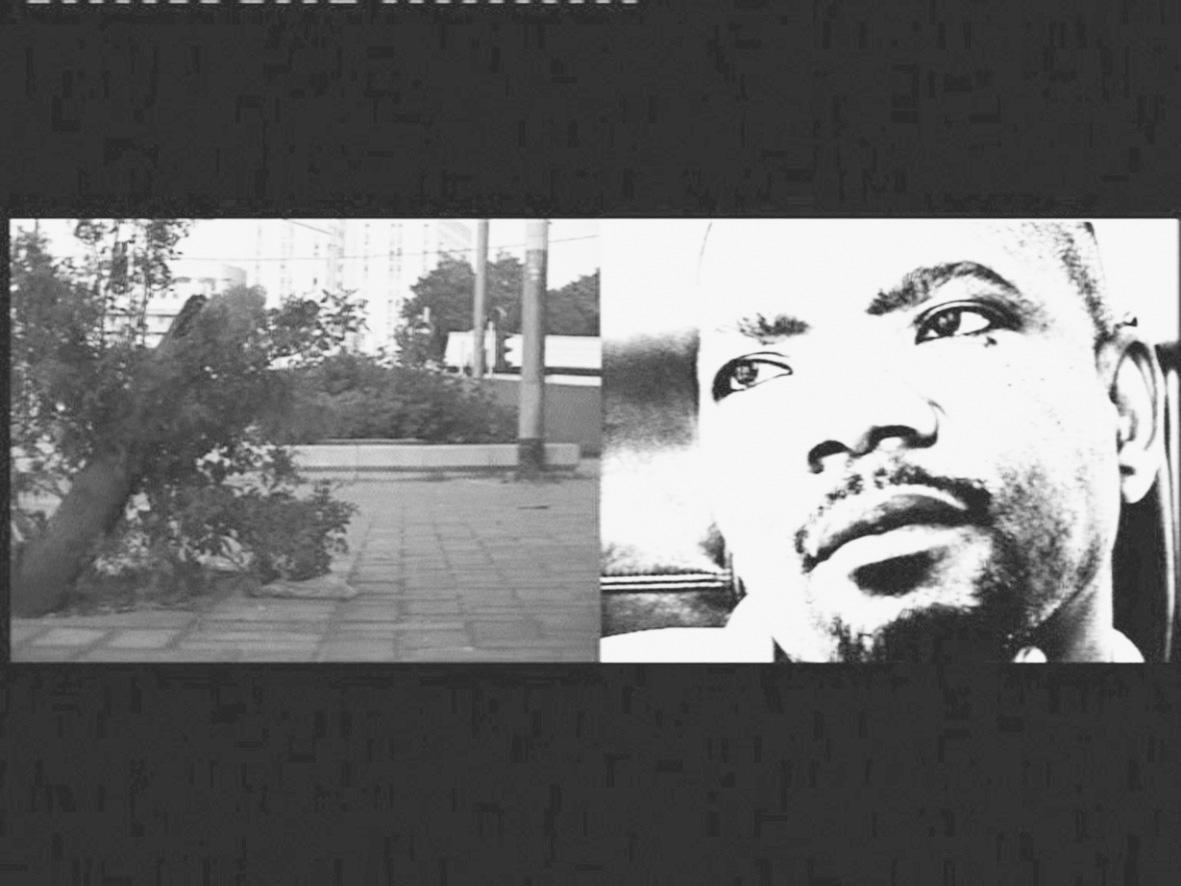

ED: For The Road Map project, Sandi Hilal, Alessandro Petti and Multiplicity made two journeys both of the same distance,first on Palestinian roads, then on Israeli roads. Finally, they showed the difference in duration between the journeys. This work was born of very simple research that showed the direct effect the wall and the checkpoints had on daily Palestinian life. It is different from any mass media report, which in most cases will deal with these issues only when a security problem (suicide bomb attack, the assassination of Palestinian leaders) occurs. Israeli media, at least mainstream, only deals with the wall as it serves the public interest, as a great success in preventing terror attacks. The price Palestinians are paying is not of any interest.

BS: Do these art-related projects reflect the inner conflicts and diverse nature of both Israeli and Palestinian societies?

ED: At least in the Israeli context, the art projects are the inner conflict. The wall is considered a positive policy by the government, not only because it is regarded as an efficient means against “terror.” It also fulfills the subliminal fantasy of Israeli Jews about breaking away from the Middle East and reconnecting to Europe by sealing the country from any influence from the region. Any project that questions the price we pay for maintaining the wall, the price the Palestinians pay, and so forth, stands in conflict with whatever is transferred through the mass media and public opinion in Israel.

BS: However, along with the number of local and international art-related projects targeting the wall,there is a constant,evergrowing focus on the region. In a way, it indicates a pattern of repetition and excess that could lead to a “normalization” process. What is your strategy against this process? Or do you already consider yourself as part of this process?

ED: You are right. The problem with many of these projects, and this is also something that was considered by Artists Without Walls in their video piece April 1st, is that at the same time as resisting the wall, they accept its existence, they provide ways of living with it. I don’t think there is an ideal strategy here that would be considered wise to follow. At the end of the day, the most valuable projects are those that are done out of sincere motivations, with a real desire to learn and influence in the long term. These are projects that are not marked by only a single event, but are also a process of collaboration and study.

BS: Digital Art Lab has been circulating April 1st in Europe. What kind of response are you aiming for?

ED: We are not circulating the work. Just like any other work, it is invited to exhibitions and festivals as part of the international interest in the wall, in some cases because of the reasons I described earlier. The problem with April 1st, as well as with any other action surrounding the wall, is that it had zero reference in Israeli media. The only media present at the event itself was international.

BS: How do you define your position as a curator in this act of trespassing?

ED: I can say that my position becomes clear to me as part of the mental process of trespassing I was describing before, the process the artists go through themselves. I see myself in the same spot, and by making this selection, I was trying to emphasize a phenomenon that is still at its early stages.