Istanbul

Borga Kantürk and Ahmet Ögüt

Platform Garanti

December 20, 2005–January 28, 2006

Only a couple of years ago you could hear people declaring advances in contemporary art in Turkey as a miracle: an Istanbul-based scene that created a critical field out of void, deprivation and political friction; a period of intense production and consequent recognition from the institutions of western Europe; the success story of the Istanbul Biennial; and a progress toward structuralization in recently opened galleries, museums and academic departments. Things should only have gotten better. Nevertheless, artistic production is now stagnant. Previous generations of artists are failing to reinvent themselves and the number of newcomers remains low.

It’s likely that the directors of Platform Garanti, one of Istanbul’s leading art institutions, recognized the deepening inertia and decided to reinvigorate the promotion of young artists from Turkey. Bringing Borga Kantürk and Ahmet Ögüt together in a single exhibition is one of the hopeful opening steps of this initiative.

In addition to their generational prominence (both are in their mid-twenties), the two artists’ earlier work shared common qualities: an almost academic devotion to mimesis, relativized by an unconcealed sense of irony; a persistent emphasis on humbleness (using “low” technology, keeping things small, short, and silent); and an openness to collaborative projects. These parallels allowed Kantürk and Ögüt to conceive a single scenario for the exhibition, merging their recent works, despite the two artists being divided between “white cube” Platform’s two exhibition rooms.

One could argue that the work of Borga Kantürk, the most active figure of the new artistic scene in the Aegean metropolis Izmir, is representative of the artistic legacy of the city. Located at the most western part of the country, relatively shielded from the cultural conflicts and political clashes that trouble the rest of Turkey, Izmir has a vital civic life. In contrast to the strong politicization of the art practices in Istanbul and Diyarbakır since the early 1990s, the Izmir scene is more limited in focus. Kantürk’s early work included laboriously produced everyday images and objects such as IDs and lottery tickets. The work that represents this early period in the exhibition is a simple replica of a mirror with a broken corner made of metallic paper, cardboard, nails and glue. On first glance the viewer mistakes it for a real mirror, then realizes that it doesn’t reflect properly, and indeed it’s suggestively titled It’s not as it seems, I can explain…

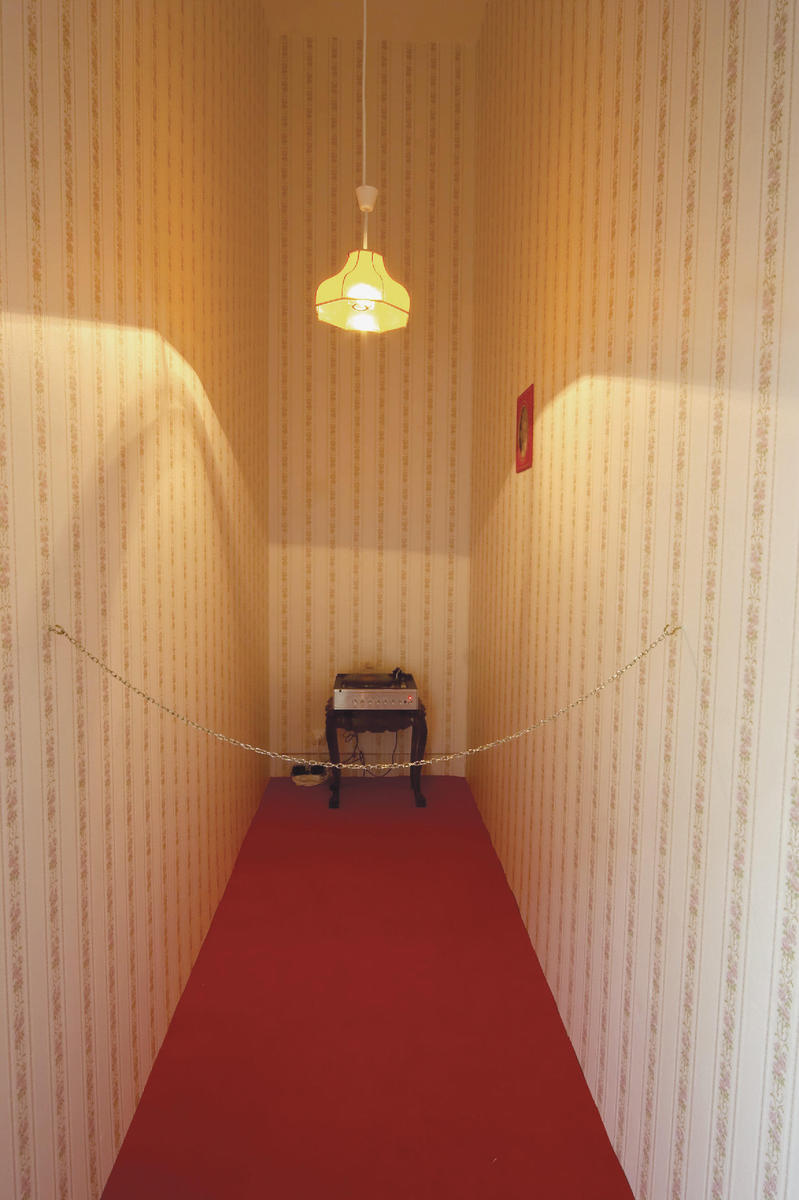

In Kantürk’s recent works, psychological effects and theatricality open his subjects to the dimension of the social. His Masters Voice, a room installation, reproduces the kitschy lobby of Istanbul’s Londra Hotel, a place mostly frequented by artists, musicians and filmmakers. The work includes old wallpaper, a dusty desk lamp and an aged turntable placed on a commode playing Turkish songs from the 50s, and clay figurines of a dog and a gramophone rotate on the record and recall the famous Victrola logo.

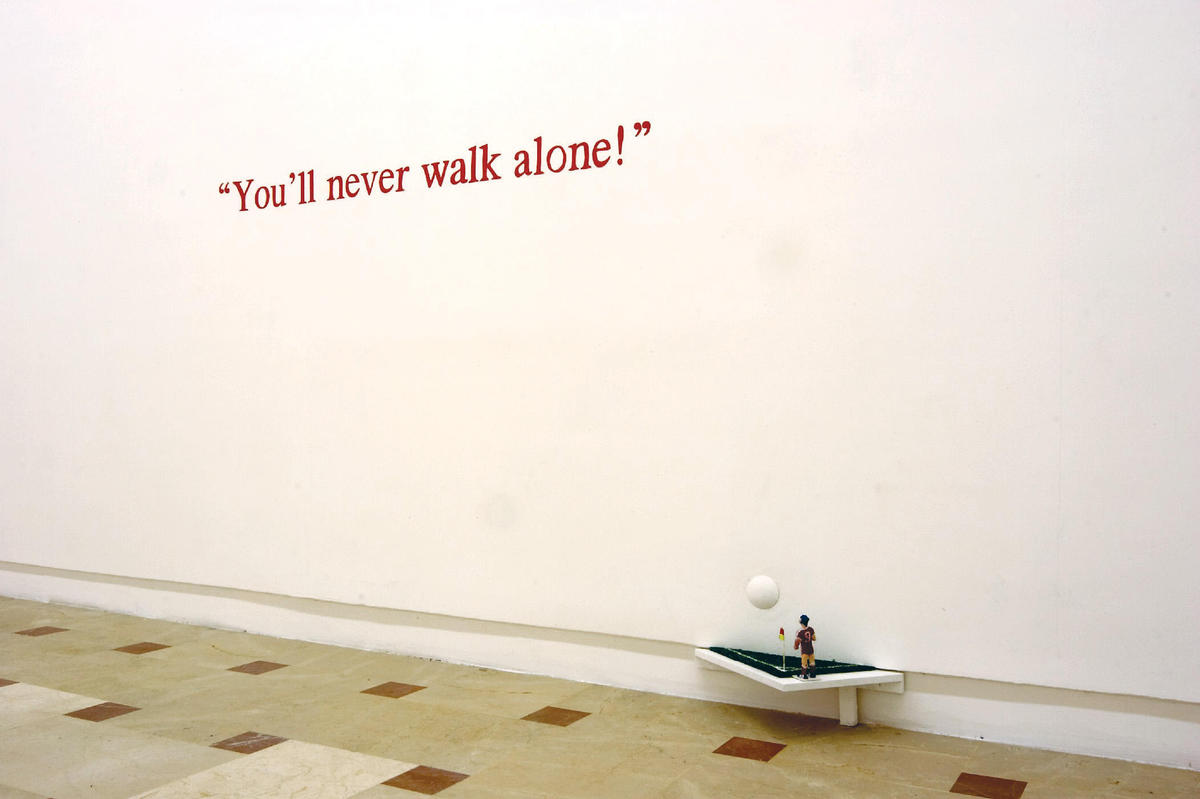

It’s hard to associate the work of Ahmet Ögüt with a single location; he was born in Diyarbakır, studied in Ankara, and lives currently in Istanbul. In his earlier collaborations with older artists, Ögüt exhibited his skills in drawing and sculpture …With Sener Özmen he produced a cartoon book based on a novel about contemporary art, and a coloring book about the political problems in the southeastern part of the country, and with Serkan Özkaya he translated a popular racist and homophobic joke into a sculpture. The photographs on view in the Platform show two young male figures in aggressive and confusing poses. (One of them is long haired and bearded, his hirsute appearance at odds with the army officer uniform he’s dressed in.) This tension between absurdity and authoritarianism also characterizes his other works in the show, in which the figure of the automobile operates as an allegory of power. The Death Kit Train shows a car proceeding in slow motion across the screen. After a few of seconds we see men at the back of the car pushing it, but then we realize that they are in turn being pushed by some others. Slowly, a long chain of men leaning on each others’ backs in a suspiciously ordered way comes into view, an arrangement not dissimilar to the scenes of contemporary mass torture and arrest we witness (via the media) in places such as Iraq today.