Donald Duck… I cannot say Donald Duck is my hero.

— Armen Eloyan

“Putting together a good painting is like putting together a good joke.” The artist Armen Eloyan’s voice is an exquisite musical instrument. It is operatic, loud, and ambiguously, if not compellingly, accented. I had to phone him up to write this piece because he does not use email. “I am dyslexic. Writing doesn’t work for me.”

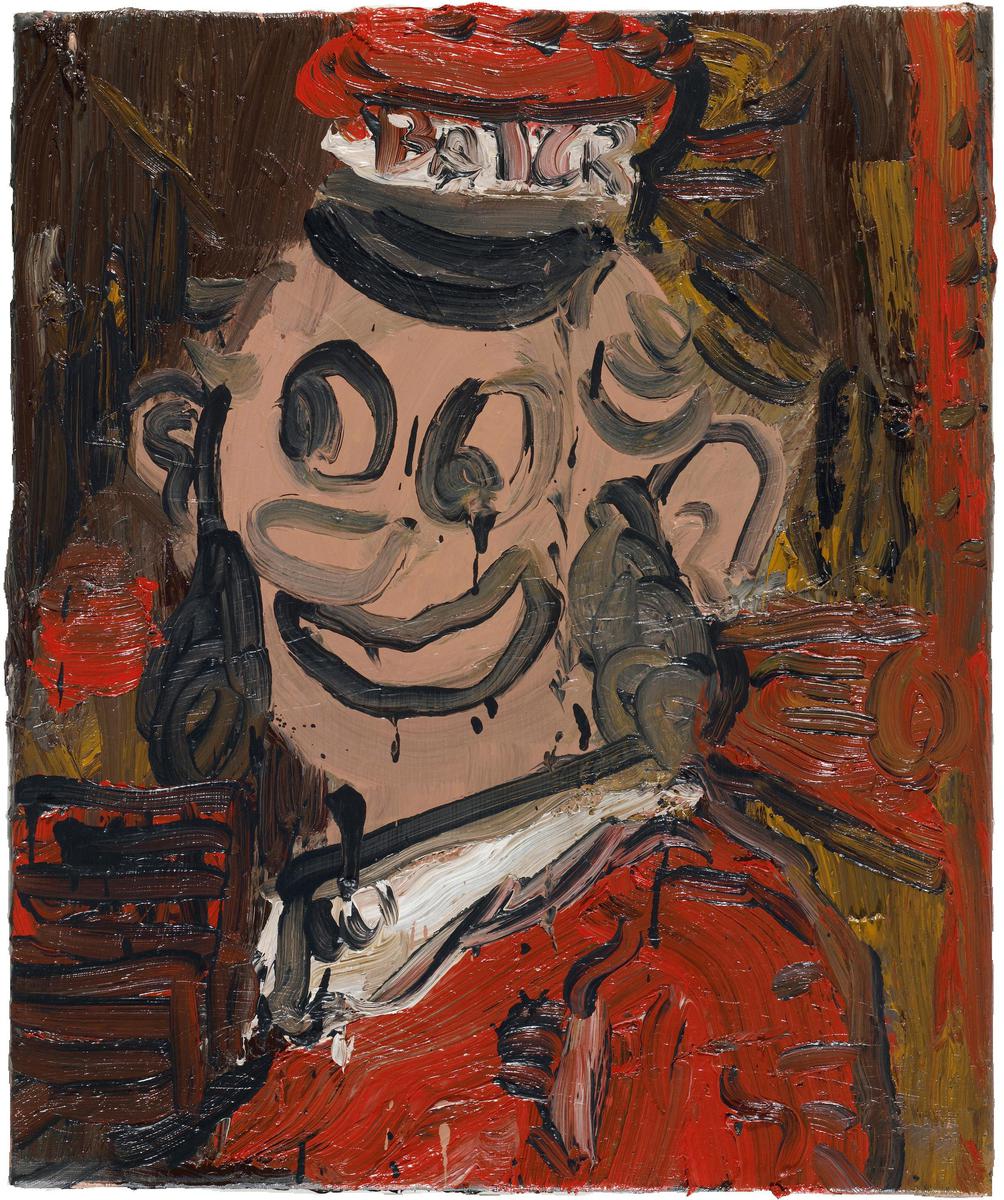

Painting does work for him. The forty-three-year-old paints mostly large-scale, mostly absurdly dramatic canvases in lush primary tones. His images are drawn from a dense, cartoon-inflected universe. Yet something about them is always off. The noses are too big, the chins are missing, the fingers droop. Figures, drawn in broad painterly strokes, seem deranged, over or undersexed, melancholic, alcoholic. There is a nameless anxiety throughout.

Would you say your paintings are dark at all?

“I don’t think so.”

Talking to Armen Eloyan, in spite of his gorgeous voice, can be taxing. He is exceedingly terse, mostly answering questions in combinations of one, two, three, or four words. Five if you discount contractions. When you lead him down a narrow path, he’ll inevitably cut you off.

What of politics?

“I am an anarchist.”

Do you think people laugh when they see your paintings?

“I don’t care.”

Is it a good thing if they do?

“I don’t know.”

Very often, it is very difficult not to laugh. Take Untitled (Painter) from 2009, which depicts the artist as a piece of wood — or rather, Pinocchio. Here, the anthropomorphic stump wears great big red shoes while a cigarette dangles from his mouth. He appears to be dozing against the wall, slumped over in exhaustion. Everywhere around him is the stuff of painting, scattered like the contents of a fallen purse — brushes, palette, paint. One can’t help but summon up a scene from a bad French movie about stunted genius. Still, it is difficult not to empathize with the familiar pathos; like Pinocchio, who dreamt of becoming a real-flesh boy, this artist dreams big. Or take Untitled (Potato), a work starring a crazed young spud — his tongue hangs from his mouth and his eyes are googly — who seems to have, in some variation of van Gogh, chopped off his own right arm. The work isn’t exactly cheerful, but its weird humor is what saves it from the unsightly realm of self-indulgent navel-gazing.

Other figures recur in Eloyan’s work beyond the ill-fated piece of wood. An earlier series featured Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. In Disaster, the iconic mouse and a white bunny rabbit (not Bugs) lay strewn over a battlefield defined by an expressionistic avalanche of brushstrokes. There is an echo of Picasso’s Guernica in its sweep and densely allegorical content, and yet, referential or not, Disaster is more than anything funny, thanks to the mouse and the bunny, their outsize features poking out from the rubble. While one might wonder if these works represent a wincingly facile comment on Disney or American culture and its material and political excesses, they are in fact more subtle, hovering somewhere in a dark gray zone between empathy and sarcasm.

So why is a good painting like a joke?

“The pieces have to come together.”

Yes?

“Timing matters, too.”

In Horny Season, a painting from 2008, a goofy dog (but not Goofy the dog-man) reclines in a garden in a scene that seems to, in sideways fashion, evoke the lush gardens of Monet. The gratuitous shrubbery is mildly sexual — the birds and the bees, the prospect of deflowering. “All of those painters were horny,” says the artist, matter-of-factly. “It’s so obvious.”

Like most of Eloyan’s works, Horny Season takes cultural references from the world around us — this time impressionist painting — as its point of departure. The paintings’ dramaturgy is in turn drawn from the world of cinema, evoking the strange alchemy of forces that make for the most powerful kind of cine-emotive effect. Hence, we witness a litany of emotionally fraught, if not familiar, scenes: the angst-ridden artist, the daydream, the stilted love affair, the professional failure.

Were you a happy child?

“I think my childhood was okay.”

Eloyan was born and raised in Yerevan, Armenia. His mother was a medical doctor, his father an engineer. Armenia under the Soviets was rich. “We had access to everything. We watched American movies, Russian movies, German movies. There was a lot of theater, too.” Cartoons from East and West. As a child, his parents would take him to the National Museum of Art in Yerevan, a massive twentieth century building whose collection was mostly made up of eighteenth-century Western European art, Armenian works, and some medieval works, too.

Was Arshile Gorky very important to you, as an Armenian artist?

“It is true, Gorky was a hero for Armenian artists.”

And for you?

“I preferred de Kooning.”

He also liked Philip Guston while growing up, the abstract expressionist cum neo-expressionist who, like Eloyan, fashioned cartoonlike figures in his work. Guston’s 1972 Painting Smoking Eating, in which a man lies in bed with his arms pinned down, a cigarette in his mouth, and a plate of food absurdly lying on his torso, is especially evocative of Eloyan’s works. If Guston mined the vaguely existential as he got older, Eloyan mines the absurd.

At the age of seventeen, steeped in punk culture, Eloyan went to work in the studio of the famed Armenian animator Robert Sahakian. He worked on coloring and graphic elements for two of the late animator’s films, learning about the peculiarities of animated cinema in the meantime.

Why did you leave Armenia?

“I just wanted to look around.”

In 1991, Armenia won its independence from the Soviet Union, and Eloyan departed. He settled in Holland, where he would have two children (twins). He ended up studying art at the Rijksacademie in Amsterdam, and about five years ago he moved to Zurich.

Why did you move to Switzerland?

“For a love story.”

He has another child, a five-year-old daughter. And he has, it must be said, an extensive array of tattoos all over his body.

At the moment, Eloyan is at work on a new series titled, Is ugly people having a good heart or they just say to take a snake out of the hole? Excitingly, it’s impossible to tell whether this is Eloyan’s Armenian-Russian-Dutch-Swiss-German-inflected English as transmitted through a bad Skype connection or a well-crafted pun. It doesn’t matter. It’s about clowns! And like the best clowns, these paintings stand to have the stuff of a well-crafted, if not terribly maudlin, joke.

Are Armenians funny?

“Armenians like humor, they like jokes. They love jokes. If I learned one thing growing up, it is how to tell a good joke.”