Dubai

Under the Indigo Dome

The Third Line

January 18–February 12, 2007

I wasn’t expecting to like Under the Indigo Dome. The pre-exhibition promotion in the local press had been about Tehrangeles and B-boy aesthetics; it sounded blokey and literal, a kind of MTV Irania. Amir H Fallah’s previous show at The Third Line, in 2005, had featured paintings that, for me, were mannered and self-conscious. I’d loved Ala Ebtekar’s drawings from 2002 and 2003, where he overlaid and framed antique Persian manuscripts with line drawings of ancient warriors, missiles, and cowboy boots, an exquisitely rendered mash-up of references; then again, his new series, The Absent Arrival, was supposed to be entirely different.

As it turns out, the two Californian artists have just aged a little, and their work has a new maturity: Under the Indigo Dome was reflective, personal, even melancholic. An exploration of masculinity rather than a rehash of the whole Iranian-American thing, Fallah and Ebtekar’s works were stylistically very different from each other, but they conversed sympathetically across the gallery.

In the show’s catalogue, Fallah describes his previous paintings — richly colored, semi-abstract landscapes of poppy blobs and shapes — as “restrained and formal.” His newer work explores his male friends’ memories of the treehouses, camps, and forts they built during childhood and adolescence. At The Third Line, the theme was worked out through photos of friends’ recreated camps (accompanied in the catalogue by interviews with the nostalgists in question), collage studies, and an installation of a fort, knocked together from wood and rope, with a few magazine pictures of sexy girls pasted inside. His theme then exploded in a series of canvases featuring warmly and precisely painted camps set against apocalyptic skies that, in contrast, dominated and threatened to overwhelm the subject.

Or maybe the dramatic skies were the subject; maybe Fallah’s project is much darker than it initially appears. Either way, the rich, vivid horizons accentuated the safe haven of the fort, and evoked early teenage (male) fantasies of facing down Armageddon from a shack in the woods. The oblique influence of sci-fi and comics on Fallah’s style was especially appropriate here.

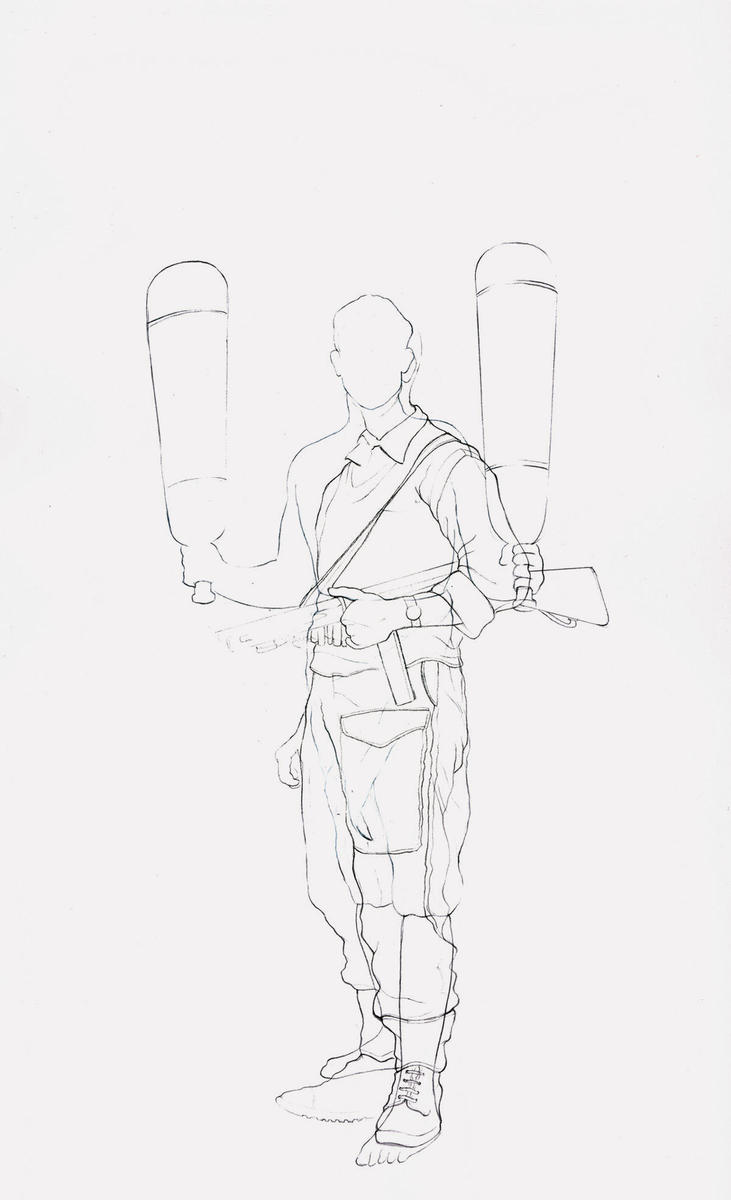

Ala Ebtekar’s new work was also a surprise. He’s still fascinated by Iranian coffeehouse culture and the large-scale paintings that hang in those traditional institutions. In the show he riffed again on the iconic figures — wrestlers, Zurkhaneh [historical sports club] trainers — that have appeared in his work previously, but at The Third Line they were layered in graphite on white paper, blurred with other figures that adopted B-boy stances and poses, as found in 1980s books and magazines and in Brooklyn-based photographer Jamel Shabazz’s images of the early hip-hop scene. Ebtekar’s subject was pared down; the drawings melded the delicate figures together so that it was hard to see where one ended and another began. A white acrylic dome-like line that referenced Ebtekar’s training in Persian miniature painting framed the figures. A couple of brilliantly executed, larger-than-life wall drawings in the same style were a highlight of the show.

The Absent Arrival could be obvious, a literal interpretation of that hackneyed theme of the split personality of the émigré (or in Ebtekar’s case, the first-generation American). But the series is meditative without being nostalgic or trite. This was Ebtekar’s first show in Dubai. It’s a shame that he was represented only by this series, which, with thirty-one related drawings, was a little repetitive, and belied the diversity within his body of work.