Paris

The Anxious: Five Artists Under the Pressures of War

Centre Pompidou

February 13–May 19, 2008

There has been a marked tendency within the art world in recent years to veer toward a sort of lens-based anthropology. While this is often celebrated as a welcome “return of the real,” it has just as often blunted art’s ability to deal with the real in any genuinely heuristic way. If art does not first attend to its own historical conditions of possibility and use, what can it possibly tell us about the world around us that we don’t already know?

That mainstream art-world institutions are all too happy to underwrite this tendency was once again borne out by ‘The Anxious: Five Artists Under the Pressure of War,’ shown in the fashionable Espace 315 at the Centre Pompidou, presenting “works of five artists who share a sense of personal involvement in dealing with the subject of the war in the Middle East. They are artists of a younger generation able to translate the oppression of a conflict into an alternative language based on the critical analysis of its causes and background in a continual reflection upon the instruments of its representation.” Or so claimed the visitor’s guide to the exhibition. But what was one to make of the wishy-washy personalizing of engagement (“a sense of personal involvement”), the dubious insinuation that art is some sort of “translating” device for elected themes, or the intellectually bracing lip-service to “critical analysis,” however unmerited? What was the point of such rhetoric, and the curatorial choices it sought to legitimate, if not to allow the institution to flirt with social engagement without offending its patrons?

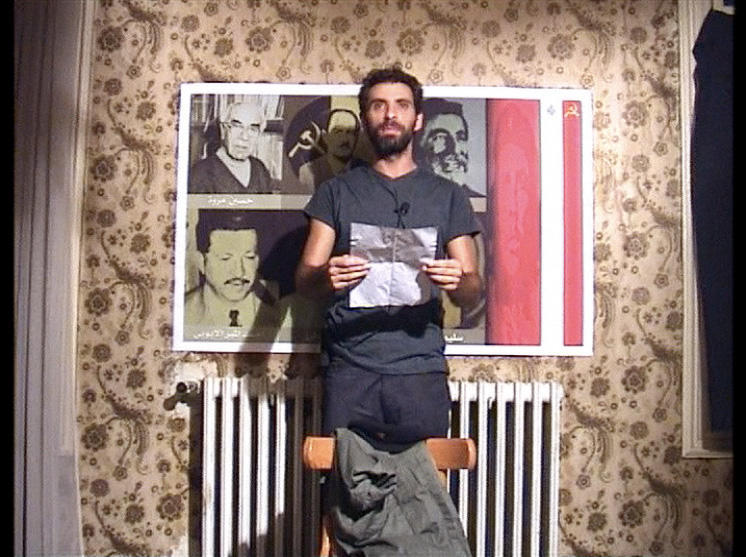

Rabih Mroué’s truly stellar video Three Posters (2004) tackled head-on both the politically symptomatic issue of the reorientation of the Lebanese resistance movement from progressive to fundamentalist and the role of video itself in the representation of the civil wars. Aside from that, though, the works in the show paid scant heed to how a uniquely self-reflexive and reality-probing activity such as art can provide irreplaceable insight into political conflict.

Hanging like an animated bas-relief just above the entrance of the exhibition, Yael Bartana’s Low Relief, a four-channel video installation depicting a crowd marching in the name of some unstated or unknown cause, seemed a textbook example of the aestheticizing of politics. Ahlam Shibli’s photographs of the West Bank village of Al-Shibli were conservative examples of a documentary genre so well known as to be tedious; indeed, human interest notwithstanding, one had to wonder whether constantly reproducing this same documentary form does not tend to reinforce and stereotype perception rather than pry it open. And though Akram Zaatari is one of the most thoughtful videomakers of his generation, the film he made for the show — depicting the “should I stay or should I go” quandaries of two resistance fighters — occasionally verged on manneristic.

Though the show described its chosen participants as “under the pressure of war,” the only evocation of the ongoing Iraq debacle was in the work of Omer Fast. His four-channel video Casting (2007) was a fictional testimony from an inexperienced American GI who mistakenly opened fire on a civilian vehicle in Iraq, killing its occupants. The four-screen installation reinforced the schizoid account of the soldier, who skipped seamlessly between his account of the events in Iraq and the apparently no less traumatic evening he spent with a racy girlfriend in Germany, where he was previously stationed.

Which brings us back to Rabih Mroué’s Three Posters, initially a performance piece but far more incisive in video format. The film was at once a seventeen-minute presentation of the extraordinary case of Jamal El Sati, who in 1985 carried out a suicide bombing against an Israeli military post in South Lebanon, and an overlapping dissection of the performance that Mroué had produced in 2000 on the same theme. Here art reflected on itself and on a decisive political issue. Decisive because prior to blowing himself up — before becoming a martyr, that is — the Communist activist videotaped several versions of himself recounting his as-yet unaccomplished deed as if it were already done, speaking from the ghostly perspective of the dead, as if martyrdom began not with death but with the tape. Mroué, addressing the viewer against a plain white background, compellingly pointed out how this raised an almost unfathomable paradox of political ontology.

But Mroué’s contribution couldn’t be expected to save an otherwise limp exhibition. Billed as highly loaded, ‘The Anxious’ turned out to be exasperatingly under-loaded — which was somewhat scandalous, given that there won’t be another occasion anytime soon in that institution to do a survey show of artists from the Middle East whose work addresses the endemic wars in their lives. And the title? Every artist in the world is “anxious” — but there was little to inspire viewers’ anxiety in this politically correct, politically boring show.