Istanbul

Yama

Marmara Hotel

January–February 2007

Six months ago, Greek curator Sylvia Kouvali convinced the owners of the posh Marmara Hotel chain to host a series of art videos on the Lumacom screen atop their venue in Pera, Istanbul. The space was named Yama [Patch] and the project launched as an experiment to show new media and video art in the public arena. Kouvali took to the task of curating the first year of monthly screenings with her program …as long as it’s dark…, a selection of works that plays with the idea of commingling spectacle and local social issues. Starting subtly with a screensaver-like series of visuals, by Swedish artist Tova Mozard, that represent interviews with members of a Los Angeles-based science fiction fan club, Kouvali’s selection then shifted to include works that take on some of the region’s more pressing political issues.

In August 2006, the local police division censored Ahmet Ögüt’s video light armoured (2006) after twenty days of screening. His short animation of a camouflaged Land Rover being hit by insignificant stones that comically bounce straight off, was deemed to be provocative and critical of the Turkish military. A few months later, to coincide with the Greek foreign minister’s visit to Istanbul following the midair collision of jousting Greek and Turkish fighter planes over the Aegean Sea, Christodoulos Panayiotou’s video Arkadaslar (2006), which shows British fighter planes from a base in Cyprus drawing the shape of a heart in the sky, was presented on the even more prominent screen of the Marmara Hotel in Taksim Square.

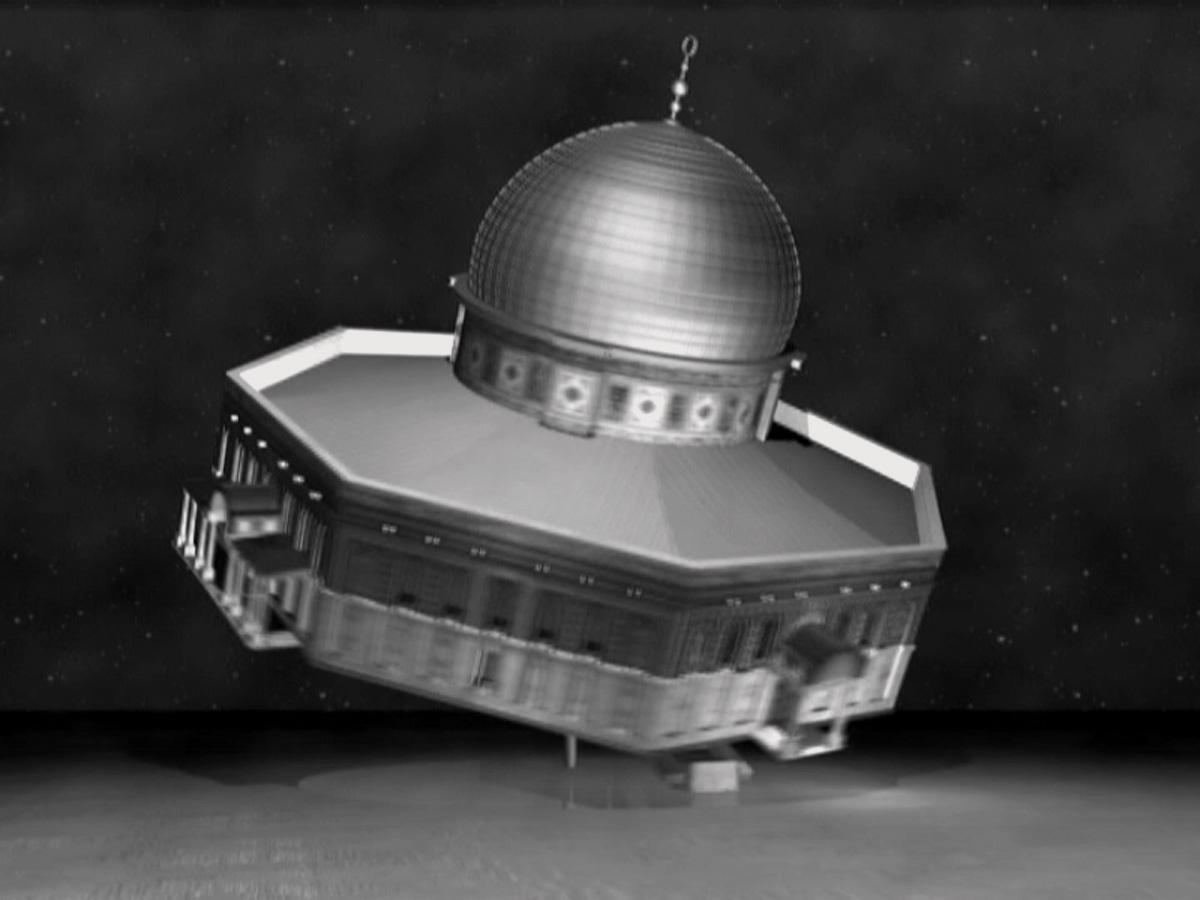

Continuing in this vein, the sixth work to be shown at Yama was Wael Shawky’s Al Aqsa Park, commissioned by the KODRA military camp in Thessoloniki, Cyprus, and first presented on a large-scale cinema screen at the base. The imagery of the video was simple — a digital rendering of the Mosque of Al Aqsa spinning on a central axis like a ballerina ride at a fair. Shawky’s version of the mosque was bleached of all color, and with its golden dome and famous blue Iznic tiles washed of grandeur, the mosque assumed a solitary, timeless, and endearing modesty.

Shawky is of course more than familiar with Al Aqsa’s importance to Muslim culture. For more than fourteen hundred years, it has been venerated throughout the Islamic world as one of the holiest sites after Mecca and Medina. It was to Al Aqsa (“the farthest mosque”) that the prophet Muhammad made his night journey from Mecca and from which he ascended to heaven to receive the commandments, including the five daily prayers, before returning to Earth to communicate them to the faithful. And the site’s importance in history doesn’t end there; Shawky used it in his work as a symbol of what he refers to as “the situation of Islam now.”

As the video progressed, the rendered mosque gained speed, spinning faster and faster like a carousel. It gradually tilted enough to reveal blinking lights beneath its foundations, an image that inspired more of a carnival sensation than religious wonder per se. Gradually, Shawky’s initially solid and calm homage to contemplation began to appear out of control; atop the hotel, hovering above the city against the night sky, Al Aqsa could easily be mistaken for a futuristic spacecraft about to lift off.

Shawky prefers to maintain his original comparison to a waltzer, a fairground ride that similarly tilts as it spins, of which he was always afraid due to the participants’ surrender to its attendant and ultimately to the ride itself. That willingness to let go, suggested Shawky, in a way mirrors religious belief — particularly given the lack of individual control that can be asserted in either case. The artificial novelty of the mosque in Al Aqsa Park worked to hybridize different systems, one of strict religion and the other of amusement and leisure. Although no literal or historical relationships connect the two realms, they both rely on another system — one of faith.

A similar chain of contradictions occurred in the transportation of a work about an Islamic site that started life in a Christian context, to a predominately Muslim city. Perhaps Turkey was the perfect place to stage such a shift — a Muslim country that is both looking to the West and boasting revered religious sites similar to the Al Aqsa Mosque in its own cities. The installation of Al Aqsa Park on one of the highest podiums in the city, a contemporary, commercial hotel in the entertainment hub of Istanbul, further excited the confusion among all those paradigms. Staged in that way, as a spectacle, Shawky’s statement was little different from the weekly light and music show that rhythmically illuminates the Sultanhamet Mosque in shades of pink, green, and blue. Yet for the public, the division between tradition and modernity, strict Islam and the new freedom of expression that the government of Turkey is attempting to promote, still exists. Although it will assume a different meaning in every place it is shown, here in Istanbul, Shawky’s Al Aqsa Park had increased resonance given the fissure generated by Turkey’s delicate balancing act of old versus new.