Four weeks after US President George W. Bush had declared major combat in Iraq to be over, British artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen, winner of the 1999 Turner prize, was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum to “create a work in response to the war in Iraq,” as the Art Commissions Committee of the IWM put it.1 As of September 2005, the time of writing, no “work” has been presented to the Museum and its public. More than two years after receiving the commission, McQueen has not “created” the commissioned project, though he has been to Iraq at least once, if only for a week and — for security reasons — in the company of British officials, in December of 2003.

When the Imperial War Museum or, for that matter, the Center for Military History in Washington, DC, commission artists to produce images related to the war, they (as institutions aligned with the military) are looking less for anti-war statements than for perspectives somehow sympathetic to the military. Painters such as Elzie Ray Golden or Henrietta Snowden, who have depicted wars waged by the US via drawings and oil on canvas, are working in the tradition of the soldier-artist celebrating the heroism of troops — even if this heroism is expressed in pictures of rather banal daily routines behind the frontline. Linda Kitson, a draftswoman who, with a commission from the IWM, accompanied the British troops to the Falklands in 1982, deliberately stayed behind the combat action (which was primarily covered by photographers) and instead produced hundreds of sketches of the everyday life of the soldiers. Interestingly, the anachronism of drawing or painting the war proved attractive to other media such as television, which pushed the oldfashioned approach into the realm of spectacle. When British artist Peter Howson was appointed by the IWM to travel through Bosnia in 1993, a BBC television crew followed him as he was following the British forces participating in the United Nations Protection Force. The next time Howson visited Bosnia, he brought his own cameraman, who produced a video diary of the experience of being a war artist in the age of electronic media.

Speculating about the type of work McQueen might provide “in response” to the war in Iraq, critic Nico Israel suspects that, “given McQueen’s filmic track record, he will almost surely produce something provocative and weighty.” Israel, nonetheless, wonders whether “McQueen [can] really learn that much more in seven days ‘on site,’ in the presence of Defense Ministry representatives, than, say, George W. Bush can learn talking turkey with US servicemen?”2 Both the expectation that McQueen would be the appropriate artist to render the war in a “provocative and weighty” manner, and the concerns that an embedded one-week stay in the region might not be enough to produce something adequate in relation to site and situation, destabilize the traditional task of artists covering the war.

If “covering” rings a bit oddly in the context of “art and war,” it also points to the peculiar vicinity of art and journalism, one especially pertinent in the case of war. That McQueen, whose multi-thematic work revolves around questions of traumatic experience, the body and the psychophysical features of the image itself, is expected to do some sort of in-depth research in Iraq, acquiring a knowledge of place and people that exceeds the expertise of President Bush, projects onto him not only the image of an artist working in the documentary mode but also one of a journalist on a mission to find a story through which it is possible to narrate history — though McQueen’s approach rarely foregrounds the narrative level of his film, slide and sound work.

Moreover, he should demonstrate, as some would hasten to add, a certain responsibility and interest in the material reality of the war, rather than relying solely on media representations and the virtual imagery of military popular culture. In the age of hyperterrorism, when rumors of the transformation of war into video game have long become hard currency in cultural theory and artistic practice alike, and where the frontline has been replaced, at least in the brains of philosophers such as Paul Virilio, by television monitors and other electronic interfaces,3 the actual visit to the site, even if limited and controlled, already cuts a difference.

The entry of artists into the field of ethnological observation or journalistic reportage is complemented by the consideration of photojournalists who cover conflict and catastrophe as artists in their own right. Martha Rosler, an artist, writer and activist, who since the Vietnam War has worked on problems representing conflict, emphasizes how the “becoming-art” of photojournalism contributes to the creation of universalist tropes in which war is seen as culturally malleable and operable, at least in the West: “The convergence from reportage to art attempts to hurry a historical process, abridging the decent interval that is supposed to elapse before war photos are taken as universalized testaments to a set of ideological themes with a powerful hold on the collective imaginary: War Is Hell, Admire the Little People, Everything Important Occurs within the Individual, and finally, The Photographer Is Brave.”4

Part of the conception of the war-artist/journalist as hero is based on the belief in his or her intimate relationship to an alleged philosophical or anthropological truth — one experienced in the heat of political turmoil and facing the gore of combat. The myth of privileged access to the very “ideological themes” that Rosler mentions is traditionally reserved for those artists and journalists who are visiting the site of war from elsewhere, instead of emerging from the local population. In other words, you have to be sent by an institution such as the Imperial War Museum or be propelled by your own will to truth to record the events and grasp the historical or existential meaning of a particular conflict. As visiting foreigner or tourist, the war artist or war journalist is equipped to translate this meaning into cultural languages that are shared by a public not present on the ground.

One of the indisputable aspects of tourism is the promise that one’s expectations of a country, a city, a place or a people are going to be fulfilled, simply because those expectations were initially fabricated to be fulfilled by the tourist industry. Similarly, for the war reporter or war artist, the search for traces of an eternal truth in most cases entails individual epiphanies on the battlefield, or among the dead and mourners in the ruins of bombed cities, if only because such epiphanies are expected to happen.

Staying faithful to the idea (or ideology) of the subjective, truth-conveying war experience — and thereby making a particular war “available” to oneself as well as others — requires a supreme act of observation and divination: to distill the universal significance from the particularities of the everyday, the endurance of civilians and soldiers, and the physical and psychological landscapes of conflict. Inevitably, almost every artist or journalist, covering a war on-site, is looking not only for moments décisives to render with pen, notebook, brush, or camera, but for a personal version of the war. One might even say the ultimate goal of the truly ambitious war journalist/artist is to become the (re)creator of a war, the maker of a guerre d’auteur.

Whether this auteurism is necessarily bad or avoidable is hard to decide and touches on rather general questions about the definition and limits of art practice. Yet certain ideas or fictions of “subjectivity” are instrumental in communicating the meaning of war whether by providing assurance of the testimonial authority of an eyewitness or through a superior visionary capacity to “see” things that are hidden from the view of the common observer or participant.

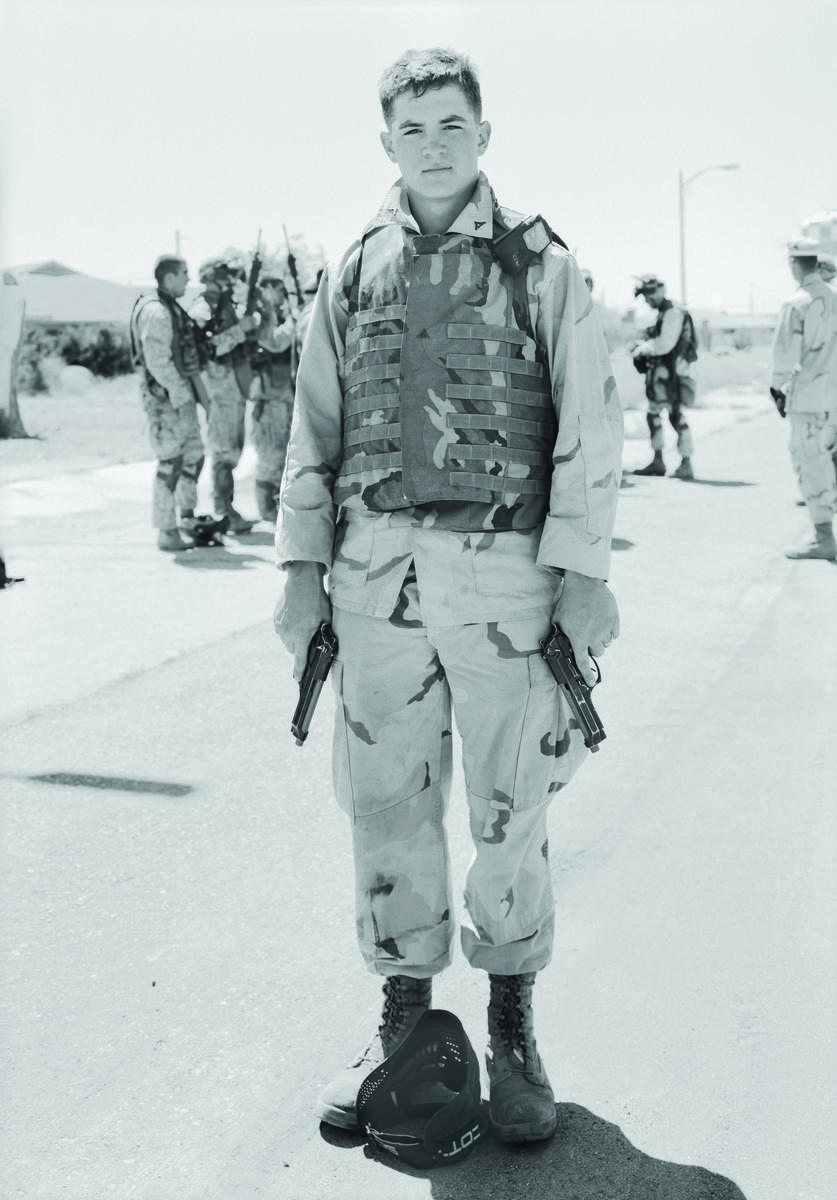

How does such a subjectivity relate to a more ironic or sarcastic stance on war and the military? Symptomatically, the work of artists coming from war-stricken societies is apparently less occupied with the pathos of the search for universal truth in (and of) war than the “visiting artist.” Consider, for example, the production of Israeli artists such as Raam Don, Meir Gal, Nir Hood, Adi Ness, Eliezer Sonnenschein and David Wakstein, all included in the recent exhibition “Die Neuen Hebräer. 100 Jahre Kunst in Israel” in Berlin. Clearly firsthand experience of military service and a society in a permanent state of emergency can lead to ambiguous results, which often border on bad humor or pop cynicism and avoid the seriousness usually demanded by official commissions. That these kitsch, campy, witty, tasteless, decorative, sexually charged articulations of subjectivity in relation to war were institutionally sanctioned5 is telling insofar it seems to mark a broadening of the range of “acceptable” responses to conflict.

That said, one should add that in some countries (such as Germany or France) whose governments and/or citizens opposed the invasion of Iraq, anti-war art would more likely represent the “official” position toward conflict, rather than attempt to understand the meaning of war in the traditional sense of war artists’ art. Therefore, as resistance to the war in Iraq is particularly strong and visible in Britain, while the behavior of the British troops over there has become a subject of fierce public debate, it’s becoming very interesting to guess what the IWM-sponsored project by McQueen will be like. His work may turn out to be an important test of the category of war art itself, since McQueen has to carefully weigh the expectations regarding the “provocative and weighty” nature of his work against the expectations associated with art about conflicts. At the same time, the British public, critically aware of the pitfalls of this particular war, could be particularly prepared to respond attentively to a work commissioned from a well-known artist by an institution whose mission is to actively control the historical and aesthetic memory of war.

1 Imperial War Museum, Corporate Plan 2004/2007, London 2004, p. 14 2 Nico Israel, “Atelier in Samara. Art and War,” Artforum, Vol. XLII, No. 5, January 2004, p. 36 3 See e.g. Paul Virilio, Kriegstaße, in Peter Weibel and Günther Holler-Schuster, ed., Mars. Kunst und Krieg, Ostfildern-Ruit/Graz: Hatje Cantz/Neue Galerie Graz am Landesmuseum Johanneum, 2003, p. 35 4 Martha Rosler, Wars and Metaphors [1981], in Martha Rosler, Decoys and Disruptions. Selected Writings, 1975-2001, Cambridge, MA/London/New York: MIT Press/International Center of Photographer 2004, p. 253 5 “Die Neuen Hebräer” were part of the celebrations of the 40th anniversary of the beginning of diplomatic relationships between Israel and the Federal Republic of Germany