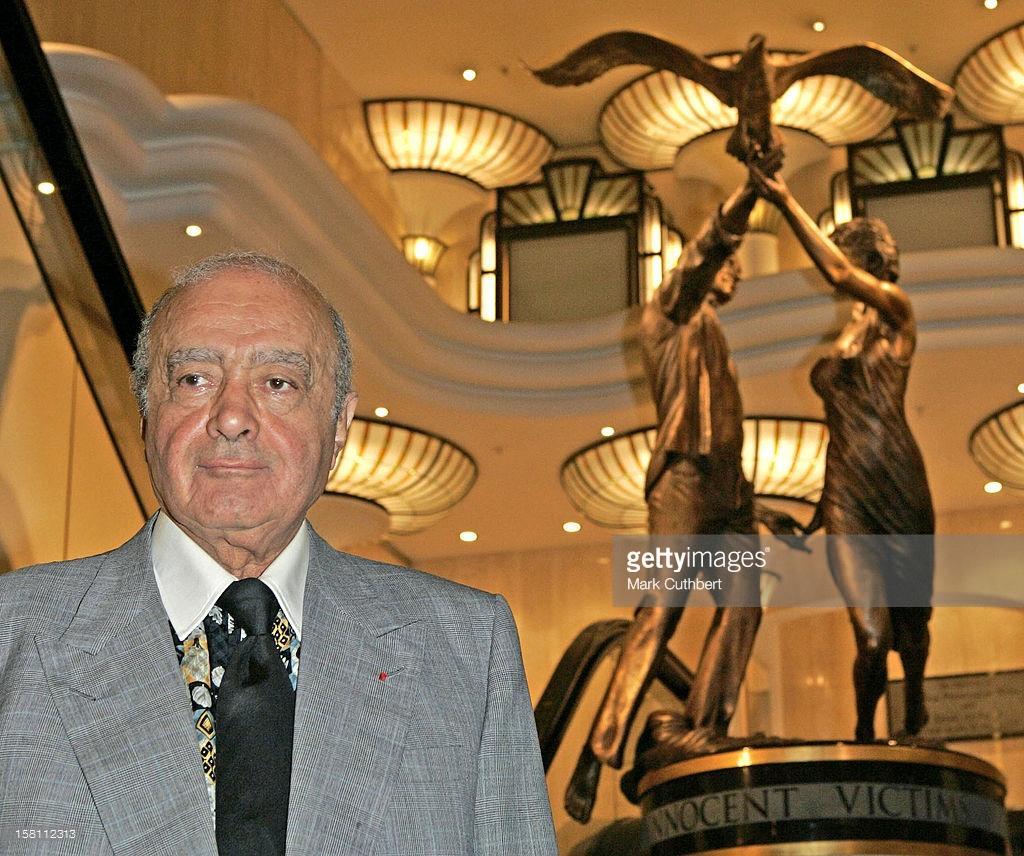

At the top of an escalator in Harrods, the Knightsbridge department store owned since 1985 by the Egyptian soft drinks salesman-turned-billionaire businessman Mohamed Al-Fayed, stands what might be London’s oddest work of public art. Entitled Innocent Victims and designed by Bill Mitchell, Harrods’ chief architect for some forty years, the life-size bronze depicts Al-Fayed’s son Dodi and Dodi’s lover, Diana, Princess of Wales, who died together in a car crash in Paris on August 31, 1997 — an event that Al-Fayed has alleged was orchestrated by the British secret service agency MI6 on the orders of the royal family. Mitchell shows the pair boogying barefoot, she in a negligee, he in testicle-hugging slacks and a tight shirt unbuttoned to the waist, as though on the dance floor of an upmarket Mediterranean fleshpot, or on the poop deck of a burnished yacht. They appear to be about fifteen minutes away from slipping off to bed for a night of flashy, trashy sex — of posh lust and poshlust. Before that, though, there is one piece of business to attend to. Staring into each other’s eyes, Di ’n’ Dodi release an albatross into the sky, its two wings inscribing the initials “D.D.” into the department store’s perfumed air, with its Obsession and Samsara, White Shoulders and l’Eau Sauvage.

Innocent Victims is, by almost every measure, a terrible work of art. It fails as a realist work — his stomach was not that flat, nor was her nose that irredeemably beaky. It fails as a symbolic work, too — the albatross, post–Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), commonly speaks either of divine grace or of the burden and eventual expiation of guilt, neither of which seem appropriate to the couple’s short history. Most of all, it fails as a representation of love, at least between Dodi and Diana. Fumbling for eroticism (his bare chest, her swollen pubic mound) it slips closer to a soft-porn fantasy about an Arab “entering” the British establishment — something that Al-Fayed, with his failed passport applications and rescinded Royal Warrants never quite managed to do. (Prince Philip, identified by the Harrods’ proprietor as the prime suspect in the alleged MI6 plot, withdrew his official patronage of the store in 2001, following what his office described, in a masterful understatement, as a “significant decline in trading relationships.”) At the very least, the sculpture seems to be a vision of what a wealthy, unimaginative man of humble birth might want for his son — a princess, utterly pliant; a princess, to make of him a prince. Innocent Victims is a memorial, then, but not so much to the actual Dodi as to a version of him — an Arab blight on an English rose — invented by the tabloid media and appropriated by Al-Fayed for his own, establishment-baiting ends. Here, the beloved departed is remembered only as a sexual martyr, a man who possessed a queen who never was.

Emad El-Din Mohamed Abdel Moneim Fayed (“Dodi” is a nickname, derived from his childhood mispronunciation of his proper moniker) was born in Alexandria on April 15, 1955, to Al-Fayed and the Turkish-Saudi novelist and socialite Samira Khashoggi. Up until his relationship with Diana, he lived mostly in obscurity (or whatever form obscurity takes when you are the son of a very wealthy man and have access to many of the people, places, and things that our blue planet affords). At nineteen, he was sent by his father to Sandhurst, the British Army’s officer training facility, to pursue a sixth-month course in what amounted to playing soldier, a program popular with rich foreign nationals keen to give their sons a little backbone and public- school sheen. The only appreciable upshot of this experience seems to have been Dodi’s new hobby of collecting regimental uniforms, which he’d wear to parade around his apartment (idle thoughts turn to him and Diana role-playing Richard Gere and Debra Winger in An Officer and a Gentleman). After falling out, he floated into a life of semi-indolence, supported by a monthly allowance of £400,000, which he reportedly often spent within the first week. A Ferrari dealership funded by his father came to nothing, as did a seat on the board of Harrods, prompting Al-Fayed to refer to him behind his back, according to Dodi’s PA Pamela Maestre, as “my stupid son.” Dodi met with more success with his occasional work in film, gaining an executive producer credit for the multiple Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire (1981), the tale of an Anglo-Jewish runner who defeats anti-Semitism to compete in the 1924 Olympics, and an associate producer credit for Hook (1991), the Steven Spielberg–directed reworking of J.M. Barrie’s 1904 stage play and later novel, Peter Pan and Wendy. Even here, though, it’s hard not to think that he wasn’t so much working as toying with Daddy’s money — Al-Fayed paid for much of Chariots, and Hook could not have been made without his permission as partial copyright holder of Peter Pan. “Playboy” is a word often used by the tabloid media to describe Dodi, and one that carries with it, alongside the usual associations of cocktails and louche daywear, the suggestion of heartlessness, not least to the Princess of Hearts. Perhaps. What seems more certain is that, as with Barrie’s creation, the billionaire’s son was a boy for whom life was a thing of little weight, a boy who wouldn’t, or couldn’t, grow up.

Despite the glossier kind of gossip columns linking him with, among others, the actresses Brooke Shields, Britt Ekland, and Julia Roberts, Dodi only truly passed into the popular imagination in July 1997, when he embarked on a love affair with Diana while holidaying in St. Tropez on Al-Fayed’s yacht, the Jonikal. The media response to this relationship — accompanied by blurred, long-lens paparazzi shots of the couple riding jet skis, alighting at marinas, and, famously, sharing an awkward, rather teenage kiss — seesawed between fascination and repulsion, with Dodi presented along old-school Orientalist lines as a simultaneously rapacious and impotent pasha (a headline from an August 1997 issue of People Weekly is typical: “In her first real post-Charles romance, Diana takes up with a controversial playboy. Is he a dreamboat — or a deadbeat?”). Although they were never given unambiguous voice in the mainstream press, the underlying set of anxieties about race, class, religion, and bloodline were clear enough. Ever since OPEC, Britain had seen wealthy Arabs make increasing incursions into, if not quite the establishment, then at least the establishment’s playgrounds, and here the son of an Egyptian tycoon — and, what’s more, one who had helped end eighteen years of Conservative rule through his part in a 1994 political scandal in which he allegedly bribed two Tory MPs to table parliamentary questions — was sharing a bed with the former wife of the first in line to the throne, and mother of the second. Despite the divorced Diana’s lack of a constitutional role, there was a definite feeling that territory had been taken. Albion’s body politic had been breached by a man who, in the confused fantasies of the media, was half-Saladin, half-robed seducer à la the TV adverts for Fry’s Turkish Delight.

The rest is history — or rather, a cacophony of competing claims of more or less dubious provenance (he was cheating on her, she had called things off, he had asked her to marry him, she was pregnant with his or another man’s child), not one of which, it seems, has entirely succeeded in drowning the others out. The press is determined that the Princess remain a restless ghost, and so, it follows, must her lover. There’s little dignity to be gained in going over this material here, and what’s significant is not what the butler or the best friend claims to have seen, but the fact that a large portion of the British public remains obsessed by the affair some twelve years after the crash. Governing this are at least two “what if?” scenarios. In the first, the crash never takes place, and the romance matures, with Diana eventually converting to Islam, marrying Dodi, and bearing him a child, a brown brother or sister for Princes William and Harry. In the second, the crash does take place, and Al-Fayed’s suspicions about the involvement of MI6 and the Royal Family are proven to be correct. Either of these scenarios would have resulted in the erosion, if not the wholesale destruction, of the House of Windsor as we know it, and their constant playing and replaying in the private imaginings of the British public points to a fuzzy dissatisfaction with being a subject people and a willingness to countenance — with mixed horror and glee — an alternative constitutional reality. Like Dodi’s military costumes, these scenarios allow the nation to imagine how it’d look as a republic, without ever committing to a fight.

Drawn in two dimensions by both his father and the media, the real Dodi is unknowable (he may not even have known himself). For the British public, however, he functions not only as an exotic Other, but perhaps also as a counterintuitive avatar of the everyman. In a monarchy, most of us are as remote from the royal bloodline as any Arab lemonade seller’s son. In a monarchy, most of us are Lost Boys, politically unwilling or unable to grow up. This enforced childishness gives rise to childish fantasies — fuck the Royals and there’s a chance you might just really fuck the Royals, and in the process open up a path toward a new, more equitable world. I suspect this is why Bill Mitchell’s sculpture of Dodi wears such tight-fitting trousers. Wouldn’t you, if you were packing a republican icon — however feeble — in your pants?