Heiny Srour doesn’t suffer fools gladly. “I try to avoid flattering the baser instincts of the public,” the 80-year-old Lebanese filmmaker tells me. It is a chilly early-summer afternoon in 2023, and we are sitting on a park bench in the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, the city she has called home since 2002. I had come here because I wanted to write a literary portrait of Srour, an obscure yet legendary figure in cinema circles. What I knew when I arrived was what most people know of her: that she was the first Arab woman to have a film in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, the documentary The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived (1974), and that she has made only one feature to date, Leila and the Wolves (1984). I knew that she was a devout feminist and socialist, a spiny pioneer whose films had been banned in her own country and across the Arab world, and that her career had stalled in the 1990s. Watching her films, I was struck by her subversive vision, her refusal to yield to the expectations of ideological foes and allies alike. I wanted to know more about her trajectory — how she became one of the most distinctive filmmakers of her generation, and what happened to her.

In conversation, Srour is at once direct and suspicious, even prickly. But once coaxed out of her shell, she sweeps animatedly across varied subjects, blending opinion and anecdote: the agonies of the Arab Left, her disdain for Hollywood, her insistence, despite sorrows and setbacks, on the life-altering possibilities of art. I learn that Srour guards her legacy closely. She says that she spends much of her time correcting the factual errors and misunderstandings floating around about her on the internet. This does not surprise me, given that nearly all her films concern women whose struggles to transform their realities have gone unrecognized — or been misrepresented.

As we talk, I realize that what Srour wants is not to answer questions but to tell her story on her own terms. So I decide to do what Srour herself has done, for decades: I watch, I listen, I record, allowing her tale to unfold before me.

Born in Beirut to an Egyptian mother and a Lebanese father in 1945, Srour grew up Jewish, her family’s roots extending back to Deir al-Qamar, the onetime capital of the Emirate of Mount Lebanon under the Ottomans. Her mother was a fastidious homemaker whose education had been cut short as a child; her father was a pharmacist. Srour was drawn to the arts from an early age; painting and ballet were her “two great loves,” which she abandoned in the face of “the contempt shown by my bourgeois family.” Raised in the shadow of an older, stillborn brother, Srour was expected to follow in her father’s footsteps. “He wanted me to replace the dead male child,” she explains.

She was sent to Beirut’s Collège Protestant Français de Jeunes Filles for grade school, but a downturn in her family’s fortunes obliged her to transfer to another French-language institution, the Alliance Israelite Universelle School, in Beirut’s Jewish quarter. Srour recalls the AIU as a cloistered environment where girls were routinely undermined and told that they were inferior in both worth and intellect.

Despite belonging to a politically marginalized “ultra-minority,” Srour found the sheltered world of her Jewish social milieu suffocatingly conformist. As for so many children of the twentieth century, movies were for her a favorite escape. Her earliest cinematic memory is being moved to tears by the visual extravagance of Sacha Guitry’s historical epic Si Versailles m’était conte (Royal Affairs in Versailles, 1954), which she saw with her father in a Beirut theater. A viewing of Federico Fellini’s classic surrealist film 8½ (1963), about a filmmaker with “director’s block,” made her a devotee of the medium.

In high school at the Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais, Srour had a life-changing experience in the classroom of the French writer Pierre Barbéris. A cinephile, he had helped found the Beirut Ciné-Club, whose screenings and director-led discussions provided Srour with another education. Barbéris introduced his students to Mallarmé and Marx; Srour remembers reading The Communist Manifesto at the age of sixteen. “It made sense of the world,” she recalls. She hurried to the library to find La femme et le communism (1951), an anthology of Marxist thinkers published by the French Communist Party. “‘In the family, the woman is the proletariat of the man,’” she says, quoting the German socialist August Bebel. “I was experiencing that in my own family very clearly.” Beirut’s mythic golden age may have been in full swing, with its jet-setting bankers, bronzed beauty queens, packed casinos, and sleek poolside Mediterranean glamour, but Lebanese laws were hardly progressive when it came to the rights of women. “You were an eternal minor,” Srour explains. “If you wanted to travel, you needed your father’s permission. The life of a woman was less important than the life of a dog! If you killed a dog, you could get up to three years in jail, but for an honor killing, you would get a single day in jail.”

Srour was studying sociology at the American University of Beirut when war between Israel and the neighboring Arab states erupted on June 5, 1967. The conflict concluded six days later, with the victorious Israelis seizing Gaza and the West Bank, as well as territory in Egypt and Syria. The dream of Pan-Arabism, which had inspired a generation, was torn apart. For Palestinians, this naksa, or setback, was defined by mass displacement and an occupation that continues to this day.

In the aftermath, Srour found herself isolated. A wave of anti-Semitic sentiment swept over Lebanon, expressed not only in popular media but also at protests. Friends began to avoid her; some even refused to look her in the eye. “I was traumatized,” she tells me. She found a political home in the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), which fought for a secular, democratic Palestine that would guarantee equality to all its citizens — a vision of Palestinian liberation inclusive of Arab Jews.

In 1969, Srour enrolled at the Sorbonne to pursue a doctorate in social anthropology under the French Marxist historian Maxime Rodinson, who had just published his critical text Israel and the Arabs (1968). That same year, a friend introduced her to a representative of the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG) who spoke of the insurgency being waged against the British-backed Omani Sultanate and foreign oil companies. On a sweltering summer day, this man said something that would transform Srour’s life. “When he told me that the reform that his group was proudest of was women’s liberation,” she recalls, “I thought I was hallucinating because of the heat.” More than a little incredulous, she set out to make a documentary film that would puncture the “conspiracy of silence” surrounding Oman’s feminist revolution.

Despite her lack of training and experience, she spent two difficult years trying to convince film producers to take a chance on a passion project that would be made in an active combat zone. She was met with disinterest and chauvinism and objectified so often that she took to wearing smock-like dresses and aging herself with makeup. The rejections took their toll. “I started doubting my sanity, which terrified me,” she told me. Srour feared she would suffer the same fate as May Ziadeh, the pioneering early-20th-century Arab poet, critic, salonnière, and feminist, whose relatives forcibly committed her to a mental institution.

Srour did have her champions. At the Sorbonne, cinéma vérité pioneer Jean Rouch had convinced her that she could make films. French photojournalist and filmmaker Roger Pic, the only professional Srour met during that period who kept his eyes on her face, also believed in her project and encouraged her to keep at it. Finally, in 1971, South Yemen’s minister of culture provided Srour and her small crew with plane tickets from Brussels, “primitive” filming equipment, and rooms at the British Embassy in Aden. Across the border in Oman’s Dhofar province, the rebellion was spreading, attracting militants from across the Gulf.

Historian Fawwaz Traboulsi, the first Lebanese journalist to enter the liberated zone, warned Srour about what to expect. He remembers her as a tenacious character, intent on capturing a revolutionary moment that seemed all the more precious for its fragility. “He terrified me,” Srour says, laughing. “He went on and on about diseases and snakes.” Traboulsi was a founding member of the Gulf Committee, a solidarity group dedicated to supporting revolutionary struggles in the region. His writings on the period evoke the desperate hopes of the people he met in Dhofar, including a teenage girl who belonged to the lowest strata of her society’s caste system: the descendants of the enslaved. Hearing of the Popular Front’s gains, she escaped into the mountains with her brother. They then took to the sea, using a car tire as a flotation device, until they reached the liberated coastline, where the girl became a student at one of the schools established by the revolutionaries.

With her cameraman and a sound engineer, Srour journey into the Dhofar heartlands, trekking some five hundred miles on foot. Filming was a grueling process. Inching deeper into rebel territory, her team hauled heavy cameras on their backs, all while dodging bombs, amid a brutal campaign of suppression she refers to as “Britain’s secret Vietnam.” During their three months in the liberated areas, Srour and her crew lived together with the guerillas, sleeping four to five people in a room, eating one daily meal and drinking oft-contaminated water. Despite the difficulties, she was captivated by the rebels, especially the women and girls, many of them barely in their teens, who had given up everything for the dream of another kind of Gulf — one beyond the reign of “oil and opportunism,” as she puts it. And women’s liberation was, in fact, central to the revolution’s global fight against imperialist aggression. (In the documentary, one male fighter exclaims “Our barometer? Women’s liberation!”, a rifle resting on his knee.)

It took Srour three more years to raise the money to complete The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived. The film’s existence is a testament to the international solidarity networks in the days of the Tricontinental. The Iraqi Students Society in London housed Srour (she credits them as the film’s “real co-producers”). Much of the editing transpired in a house she shared with South Yemeni workers and their wives; Srour was assisted by members of the independent film collective Cinema Action, including the Portuguese director Eduardo Guedes. Her future husband, an Iraqi exile, helped write the commentary; a member of the Berwick Street Film Collective shot the stills. Fundraisers organized by Arab students and workers in the UK edged the project toward completion. Taher Cheriaa, the influential titan of Pan-African cinema (“a father to us all,” says Srour), risked his position as cultural director of the Francophone countries’ Agency for Cultural and Technical Cooperation by championing her film. When there was no money, Srour relied on this complex network to pursue what she drolly calls “international begging.” All the while, she hid her life as a filmmaker from her family. “I was lying through my teeth,” she admits.

The Hour of Liberation remains the most striking visual record of the Dhofar Rebellion. It’s a blistering watch, fusing archival footage with political analysis denouncing British imperialism and regional petrocrats. Srour’s film foregrounds the voices of the victims of British air strikes, of the children starved by blockades, of the tribal chiefs who set aside generational vendettas and the goat herders who shared their waterholes with the guerrillas. Women, too, are in the foreground, plowing liberated farms, painting their eyes with kohl, patrolling, reading cross-legged at the revolutionary study circles, blowing plumes of bukhoor into the darkness. Illiterate teenage shepherdesses pick up weapons and join schools, unshackled hunger shining in their eyes. A ferocious desire for a new way of being and living unites Srour’s subjects.

Srour’s film was the first by an Arab woman to be selected for the Cannes Film Festival. Despite this honor, it proved too incendiary to be shown in the Arab countries (with the notable exception of Algeria). It was even banned in Lebanon, and it would remain so for forty-five years. Srour’s family wasn’t too pleased with her achievement, either. When the news reached her father, he sent her a one-way ticket back to Beirut. “He said, ‘Come on your knees, kiss my hand, and apologize, because making cinema is a disgrace,’” Srour remembers, adding, “Cinema was like prostitution.”

Still, the impact of The Hour of Liberation was palpable. At screenings, audiences chipped in to support the revolution. “People would leave the cinema and come back with bags full of medicine and donations,” she tells me now. Even after the Dhofar rebellion’s untimely defeat in 1976, the film was changing minds. Srour was told about a group of North Yemeni soldiers who obtained a copy of the film during a lull in the fighting. They were so moved by the spirited testimonies of the guerillas, children, and shepherdesses that they laid down their weapons, refusing to fight their South Yemeni kin. “That is my Grand Prix,” Srour smiles. In the late 1970s, a Farsi-dubbed version of The Hour of Liberation circulated among the Iranian diaspora, clandestinely reaching Iran in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution. Reputedly, Khomeini himself saw the film and was so influenced by it that he ordered the last Iranian troops out of Oman.

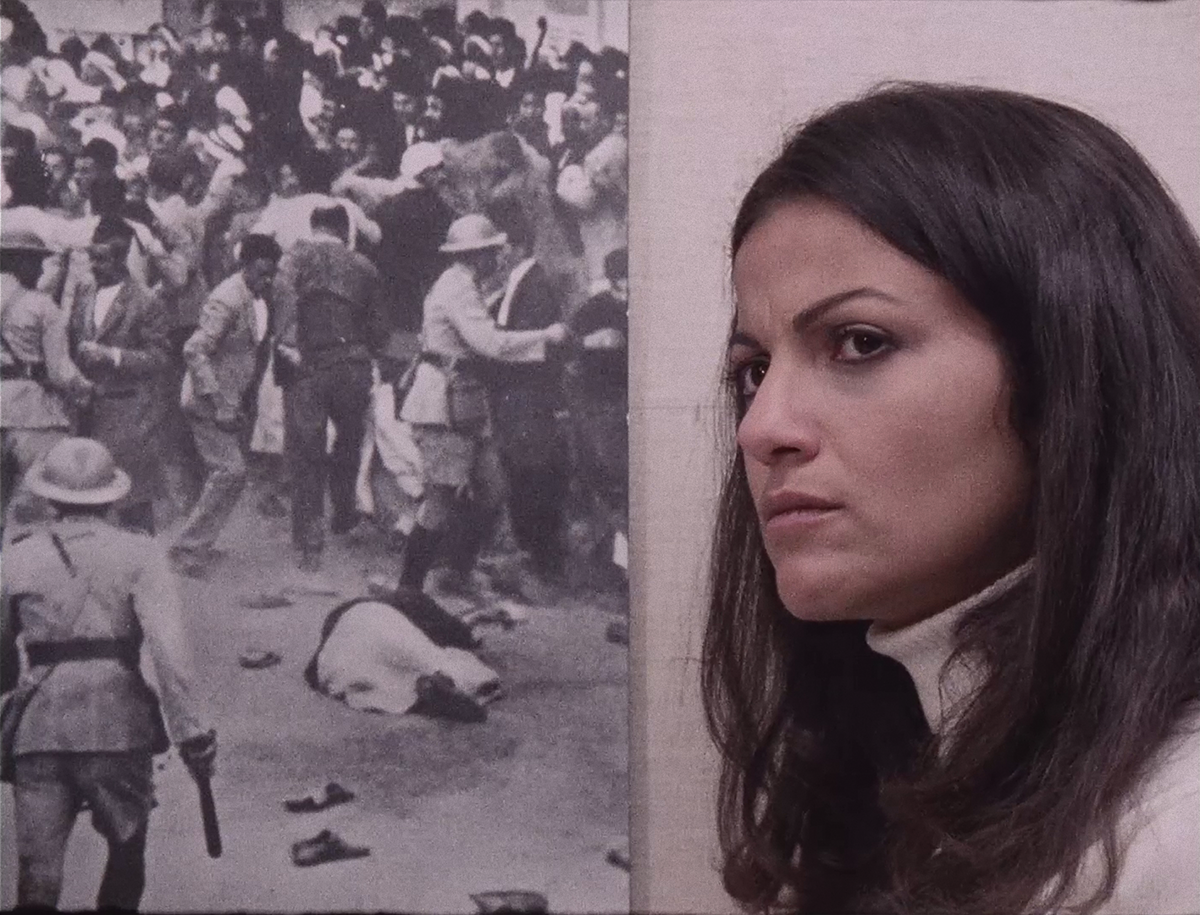

If The Hour of Liberation was a kind of propaganda exercise (in the best sense), capturing a political convulsion as it occurred, then Leila and the Wolves is something else altogether. Part fairy tale, part elegy, Srour’s second film spotlights the disappeared realities of Palestinian women, reanimating the past to tell a story about the fractured present. Leila and the Wolves braids together three calamitous epochs — the uprisings against the British Mandate of the 1930s, the Nakba of 1948, and the Lebanese civil war of the 1970s — by way of dramatic reenactments, along with newsreels and other archival footage. The film announces that it is based on actual events that inform “part of the collective memory of the Lebanese and Palestinian people.” What follows is, as John Akomfrah once described it, a “survey of mythic and symbolic protest.” The eponymous heroine is played by the arresting Nabila Zeitouni, best known for her performance in Bennesbeh Labokra Chou? (What About Tomorrow?), Ziad Rahbani’s hit 1978 play about life during wartime. Leila appears as the film’s “feminist conscience,” in Srour’s words, a time-traveling figure who cycles through various guises over the ages. Bathed in gleaming white, she is spectral, drifting through destroyed villages and razed cities. She alternates between personas: onlooker, prisoner, bride, artist, freedom fighter. She must be as duplicitous as the wolves — imperialists, refugees turned settlers, fathers, husbands, sons, the fedayeen — to survive them.

In Leila and the Wolves, Srour upends the traditional role of “witness.” There’s nothing exceptional about Leila’s suffering. It is something she shares with the countless sisters with whom she walks along a historical continuum. Srour suggests that Arab women are not afforded, and cannot afford, singularity. She neither laments nor valorizes this condition, preferring instead to illuminate the inner worlds of those who live it.

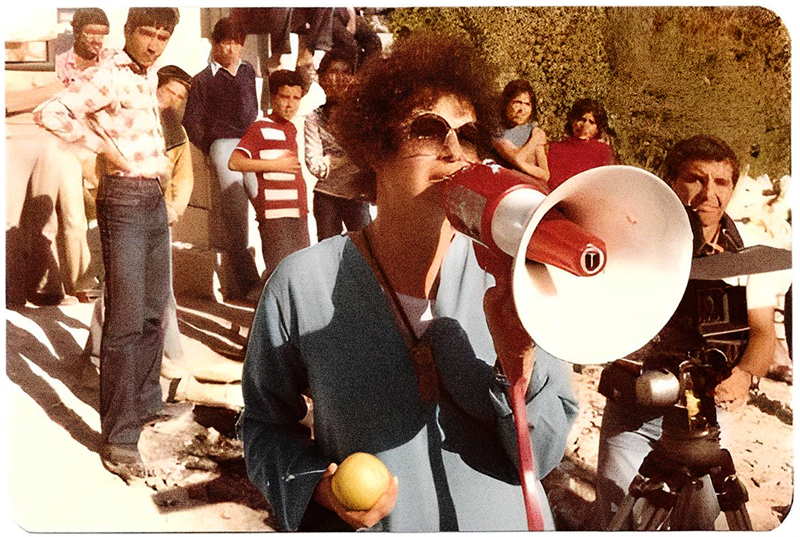

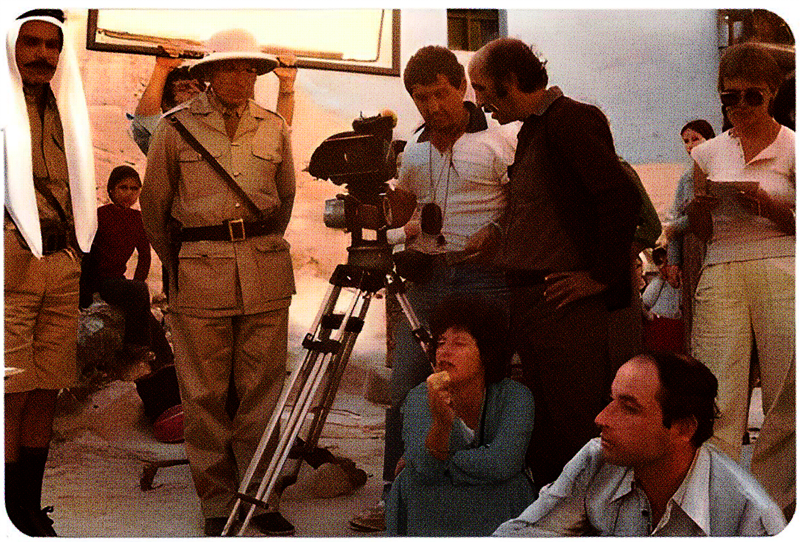

Srour wrote the film in 1979 and began shooting its first part in 1980 in a battered West Beirut and various Syrian villages. The following year, the British Film Institute withdrew funding from the project out of fear for the crew’s safety. “We nearly got killed in Syria,” she explains, recalling the day they were filming in the coastal city of Tartus. The scene they were shooting featured hundreds of extras performing a noisy demonstration led by Palestinian women. Hearing the anti-occupation chants and seeing the banners, the police mistook the actors for actual protesters. Srour’s temper rises, her voice filling the air, as she relays what happened: “I saw a man with a Kalashnikov. He was pulling the trigger. I screamed at him, ‘How dare you interrupt my shoot! Can’t you see these extras have killed me for two hours? I was rehearsing with them for two hours, and now you come and interrupt? This is the best film in the Middle East!’” The officers backed off. Later, she discovered that the extras had been local factory workers; her production assistant, “like a typical Ba’athist,” had intimidated the women into appearing in the film. They had been told that if they didn’t participate, they would be fired. Srour makes a face. “After Leila and the Wolves, I realized you need enough money to make a film without brutalizing the people around you.”

Finishing the film wasn’t easy, either. Srour did so with the help of Omar Amiralay and Mohammad Malas, two giants of twentieth-century Syrian cinema. Amiralay kindly advised her and introduced her to a production manager. He also asked her to hide her Jewish roots. She is still saddened by the predictability of his request: “The first thing they want to know about you in the Middle East is not your politics; it’s your religion.” Even after the film’s release, trouble ensued. At a screening in Nairobi, Srour discovered that Leila and the Wolves had been banned by the Kenyan authorities, ostensibly because of its pro-Palestinian slant. Srour refused to be among those who “swallowed the shit.” Instead, she disregarded the presence of police officers and their dogs and turned toward the audience. “I started singing ‘We Shall Overcome,’ and it broke the fear.”

It’s hard to parse which battles Srour seeks out and which find her. What is clear is that the risks she has taken have defined her as much as they have hindered her career. Her allegiance has always been to the revolution’s participants, rather than to its observers or sympathizers. Her films eschew the nineteenth-century-bourgeois idea of a “commitment to harmony,” which she astutely identifies as a useless trope in conventional storytelling. “Our societies have been too lacerated and fractured by colonial powers to fit into those neat scenarios,” she has argued. In Leila and the Wolves, Palestinian women rain eggs, stones, jars, and boiling water down on the heads of British soldiers. Forced to forego feeding their children, they sell their jewelry to arm the guerillas. Women whisper their plans, fool soldiers, and flirt with collaborators at checkpoints. Some fret over their husbands’ threats of taking second wives; others practice their shooting skills. Meanwhile, the mundanities of life continue.

Srour’s film also accounts for the fate of the revolutionary woman failed by the revolution. Violence, intimate and catastrophic, saturates the frame. Wives wield hot water against the occupiers, then use it to dutifully wash the feet of their abusive husbands. Fighters discuss an older man who seeks death on the front line, wild with remorse for the daughter he murdered years ago in an honor killing. “For what crime was she buried?” Srour’s chorus of women ask, echoing a Qur’anic verse. Srour is attuned to how women live with — and bear the brunt of — cruelties that erode the spiritual highs of camaraderie. A mother conceals bullets under her daughter’s bridal dress, reminding the young woman, “The fighters in the hills are suffering even more than us.” This isn’t a worldview that glibly likens colonizer and colonized, united in nefarious kinship. Wrestling with the nature of violence under colonial subjugation, Srour magnifies its festering contradictions. She is interested in what happens when a people suffer together, even as they are pulled apart.

Watching the film, I am reminded of another Leila, the narrator of Algerian novelist Assia Djebar’s lyrical documentary The Nouba of the Women of Mount Chenoua (1979). Djebar’s Leila is an architect who returns to her mother’s native mountain village, driven by her need to understand her place in this landscape of disturbed sleep and “broken memory.” There, she listens to women’s recollections of the struggle for independence under French occupation, including tales of rolled-up sleeves, kneaded bread, and torture. A lesser-known story emerges from the shadows: that of Zoulikha Oudai, an anti-colonial activist known as the “the martyr of Cherchell” who was tortured and killed by French soldiers. “All the women wandering in the past, became my mother,” Leila reflects.

Like Srour, Djebar faced social and familial opposition as she pursued a creative life. Born Fatima-Zohra Imalayen, she spent her early twenties in Tunis, where she worked alongside Frantz Fanon as a journalist for the National Liberation Front’s newspaper, El Moudjahid. The difficulties she faced there, as well as the familial pressures that led her to adopt her literary pen name, make vivid the gendered inequities of who is permitted to narrate the revolution and who is reduced to a ceremonious symbol in its aftermath.

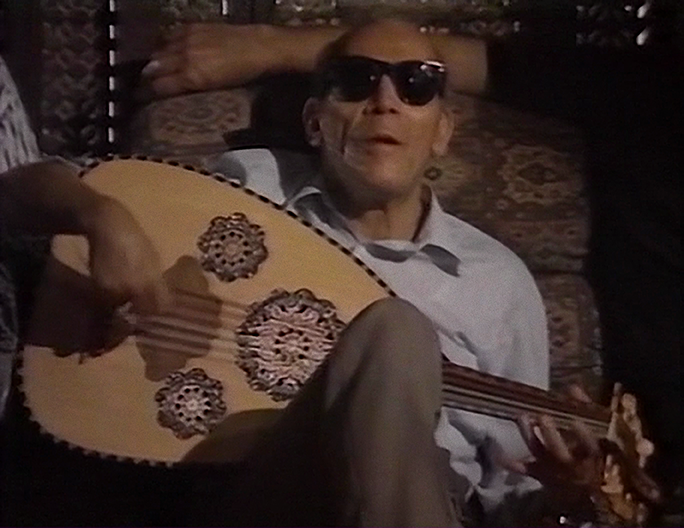

Srour’s imagination has always been fired by individuals who give heartfelt expression to the thoughts and dreams of a teeming plurality. After Leila, Srour spent nearly a decade trying to complete a full-length documentary on Sheikh Imam. the Egyptian lutist and folk singer known for his protest songs and partnership with the famed colloquial poet Ahmed Fouad Negm. Though arrested many times and banned from television and radio, his popularity was undimmed. While financial problems eventually derailed the larger project, a short profile, The Singing Sheikh (1991), produced for Britain’s Channel 4 Television, offers a glimpse of her ambitions. Srour’s camera captures Sheikh Imam, blind and wizened, being led by children through Cairo’s streets. She documents his daily habits and neighborhood interactions, interspersing his private prayers and public performances with scenes of city life. Laborers sweat, peddlers hawk their wares, women guard their fruit stalls. Sheikh Imam’s songs of bread, broad beans, and dignity serve as the soundtrack to unfulfilled dreams. As in Leila and the Wolves, there is a cost to bearing witness: Sheikh Imam describes the midnight concerts he used to perform from his jail cell, singing to fellow inmates through the bars. He is the quintessential Srourian subject, an unwavering cry of dissent heard across the villas and the slums.

Other passion projects were similarly derailed. Dance of the Dagger, a feminist retelling of the Arabian Nights, received encouraging feedback from the esteemed British producer David Puttnam (Chariots of Fire, The Killing Fields), among others, but her proposed television script didn’t align with the propagandistic climate of the Gulf War. Once again, the sorts of stories she wanted to tell undermined prevailing narratives in and about the Arab world.

For her 1995 documentary, Rising Above: Women of Vietnam, Srour profiled a cohort of women who had participated in the resistance efforts that won the Vietnam War. Twenty years after liberation, the women revisit their youths, detailing the reality behind their iconic role on the world stage as fresh-faced, gun-toting revolutionaries: “long-haired warriors,” as Ho Chi Minh dubbed them. Nguyen Kim Lai, the teenage Guerilla Girl who was photographed capturing a shot-down American pilot, Bill Robinson, tells her children the story of the American who fell from the sky and into her command. After the war, Kim Lai became a nurse and met her husband, a man whose mental illness was induced by his experiences during the war. He loved her, and she knew she must care for him. “Capturing the pilot wasn’t heroic, but marrying my husband was,” Kim Lai explains. Võ Thi Thang is another subject of a viral Vietnam War photograph, displaying a breezy smile despite having been tortured and sentenced to twenty years of hard labor by the South Vietnamese government for participating in the Tet Offensive. “Will your government still be here in twenty years to keep me in jail?” she defiantly asked her captors. Srour follows Võ Thi Thang in her new role as a stateswoman. A third subject, Dr. Duong Quynh Hoa, was a Communist fighter who became deputy minister of health after the war. She resigned, two years later, as a protest against corruption. “I didn’t want to be a myth,” she explains from the maternity clinic she now runs.

Srour’s documentary unwinds viewers’ assumptions about what it means to fight for liberation. Every revolution is a hall of mirrors, its actors performing and maintaining necessary illusions. In her plight, the revolutionary woman titillates her allies; her stylized empowerment enrages her foes. She peeks out of the bushes, perhaps to become immortalized by a camera. To be an icon is to be frozen in time and place. But Srour is committed to defetishizing the revolutionary woman. Rising Above is disinterested in camo-clad fantasies, searching instead for what remains after the global spotlight has wanders off and conflicts disappear from the headlines.

Back in Paris in the early 2000s, amid the end of her marriage and the death of her father, Srour turned to painting as well as other less stressful ways of expressing herself. In 2007, she received an award that allowed her to begin work on a film about the iconic rebel and educator Layla Fakhro, one of the heroes of the Dhofar Rebellion, who had featured in The Hour of Liberation. Born to a prominent Bahraini business family, Fakhro had served as head of PFLOAG’s cultural committee in the late 1960s before relocating to Dhofar. Srour immediately bonded with Fakhro, who went by the nom de guerre Comrade Huda. At the revolutionary school she founded, Fakhro painstakingly hand-wrote curricula, taught basic literacy, and cared for orphans, while encouraging her male pupils to try to persuade their parents to send their sisters to school, instead of marrying them off to older men. She died in 2006; Srour’s proposed film, Layla and Huda, would chart the arc of her life.

The Fakhro family was initially enthusiastic about the project, but things unraveled after they imposed what Srour describes as “impossible and humiliating” conditions on her for fear of ruffling feathers back in Bahrain. It was, Srour maintains, a painful reminder that the hostility toward her work had not diminished, even decades later.

The collapse of Layla and Huda cost Srour dearly. She lost a great deal of money and ended up on the streets for a time, living in a church that sheltered the homeless. She hid her situation from her mother, unwilling to break her heart. Her wider family was unsupportive. “I can’t count on them for anything,” Srour says, attributing her lifelong ostracization to her anti-Zionist convictions. Still, she was dreaming up new ideas. While staying in a hostel, she started a project on the sans-papiers, the undocumented migrants who lived in her neighborhood: “I wanted to defend their right to be different, while acknowledging how France was changing.”

This is where Srour stopped her story when we met in 2023. Our conversation preceded the events on October 7, and her name and films have circulated with greater and greater momentum ever since. The ecosystems of festivals, contemporary critics, connoisseurs of militant cinema, and social media have reinvigorated interest in Srour’s filmography. Her work continues to inspire younger generations wishing to confront the deathly inheritances of old worlds as well as the tantalizing possibilities of new ones. When I got in touch with Srour again recently, on the eve of her films’ North American premiere (half a century late), she explained that she has been overwhelmed with restorations, anniversary screenings, and talks, though she believes she deserves more than the appreciative backslap of a retrospective.

She tells me that her dream now is to make a feature film about world hunger, blending the surreal with the hard-hitting reality of the global food crisis. Her own grandmother lost a child to hunger, and Srour remembers overhearing her stories when she was young. Srour is also at work on a memoir. “My life is an epic,” she says, and what I hear in those words is that she knows it is still unfolding.