Footnotes in Gaza

By Joe Sacco

Metropolitan Books, 2009

In November 1956, two massacres of Palestinians by Israeli soldiers occurred in the Gaza Strip. As tends to happen, both were almost immediately subsumed, by the Suez Canal crisis and other successive crises in the region. Episodes of comparable horror and greater political import took over the headlines, and the events in Gaza disappeared into the sediment of the conflict. Joe Sacco, the venerable war-reporter-cartoonist, had read about one of the massacres — the shooting of 275 men in Khan Younis — and, on a reporting trip to Gaza in 2001, spoke to some survivors. According to a Hamas senior official whose uncle was among those killed, the episode “planted hatred in our hearts.”

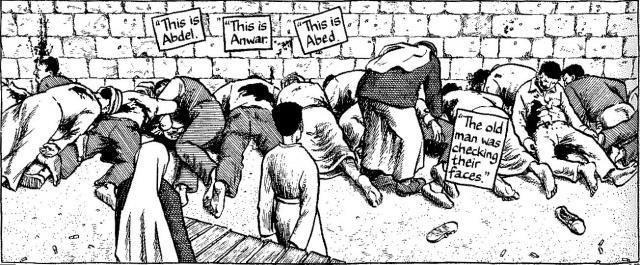

Months later, after the article he had been working on was published (with the part about the massacres excised), Sacco decided to return to Gaza and further investigate what had happened in 1956. The second incident caught his attention as he was doing research: Israeli soldiers had been searching for guerillas in Rafah and called for all men to gather to be screened; the soldiers for some reason panicked and began firing on residents, killing more than a hundred of them. This episode, too, had nearly disappeared, save for a couple of painfully judicious sentences in a United Nations report.

What Sacco has done in Footnotes in Gaza is exhume those two massacres and, in a deftly told and richly illustrated narrative, bring them back to life — not only through the memories of the people who survived them, but through the lives of the many Palestinians who are shaped by them still. Sacco — represented, per usual, as a gangly, fat-lipped, camera-toting blot on the landscape, his eyes concealed by spectacles — roams Gaza in lockstep with his fixer, who arranges interviews and acts as the author’s perennial companion. As in Sacco’s past books, the fixer (this time a native Gazan named Abed) mediates between the reader and the journalist’s subjects: though from the English-speaking upper class, he’s still struggling to make a living. The fixer channels the ambitions and ambivalence of his brethren — the awkward balance between resenting and yearning for the West, despairing and feeling hope for the future. Abed in particular embodies the connection between the daunting accumulation of historical fact in Israeli archives and the reports of the NGOs and the fragmented memories of traumatized Palestinians; through him, Sacco melds the horrors of the past and the deadening life of Gaza in the present.

Sacco makes no attempt to achieve “balance”; there are no statements from the Israel Defense Forces, no equation of human suffering and the exigencies of domestic politics. He focuses on the lives spent in dusty refugee camps and smoke-filled, single-room dwellings, training his eye on the exhausted faces of veteran resistance fighters (though they’re hardly fighting anymore). One of them is Khaled, a militant on Israel’s “wanted list” who has been living underground for years, traveling from safe house to safe house, stopping by his own home every so often to see his wife and son. “The boy insists on being woken up to play with his dad no matter what time he shows up,” Sacco writes, the text floating above a child clad in pajamas who struggles to stay awake while his father regales the journalist with stories of intifadas past. “Khaled’s wife is expecting again,” Sacco notes as their conversation is ending. “Khaled says her relatives encourage her to have more children as soon as possible. They wonder how much longer Khaled has to live.”

Pathos and fact command Sacco’s attention equally; while his writing is unadorned, alternating between the language of historical documents and interviews — save for the occasional authorial interjection — his illustrations illuminate the page, transporting the reader from rubble-strewn battlefields to claustrophobic domestic scenes to expansive cityscapes. If Benny Morris’s The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem and the work of Israel’s other New Historians focused attention on the mess of nationalistic narratives around the country’s signature conflicts — 1948, 1967, 1982 — Sacco steers attention toward the calamities whose symbolism is eclipsed by their arbitrariness, and which form the architecture of daily life rather than the spectacles of politics. The massacres he narrates are but two of the manifold roots of the anguish that simmered beneath the stagecraft of the post-Oslo period — episodes that have become such a part of the fabric of life in Gaza that, Sacco notes, even those who lived through them have a hard time distinguishing between them. Those who do remember would just as soon not speak about it, or else they wonder why Sacco is interested in these forgotten historical episodes rather than the suffering of Gazans today.

In the end, Sacco is not quite sure either. The story of the journalist seeking to relate a discrete episode, or a neatly packaged piece of the horror of war, and ending up with a tale that lacks a clear beginning or end, an arc or hook, logic or relief, is not a new one. But whereas for many journalists this personal revelation becomes a cheap hallmark of the war-reporter-turned-author, Sacco allows his characters their own ambivalence, which he records from a slight distance. Of course, that distance, too, diminishes over time. Toward the end of the book, Sacco tells of an interview with a man named Abuh Juhish, who was in Rafah in 1956. He remembers — or chooses to remember — little beyond the fear he felt that day. “Suddenly I felt ashamed of myself for losing something along the way as I collected my evidence, disentangled it, dissected it, indexed it, and logged it onto my chart,” Sacco writes. “And I remembered how often I sat with old men who tried my patience, who rambled on, who got things mixed up… how often I sighed and mentally rolled my eyes because I knew more about that day than they did.” Sacco — young, stolid, and set to leave Gaza the next day — sits across from Abu Juhish — ailing, tearful, and destined to die in Gaza — in silence for a moment before ending the conversation.