Dubai

Life Drawing: Approaches to Figurative Practices

The Third Line

December 19, 2007–January 13, 2008

‘Life Drawing,’ the most recent of The Third Line’s occasional group shows featuring emerging female artists from the region, presented four distinct encounters, in different media, grappling with the fraught question of representations of women in the Middle East. The artists addressed familiar (Western) feminist concerns about the status of women in the Middle East — the veil, violence against women, the lack of equality, rights, education, etcetera — but they managed to introduce complexity and nuance into traditional, often frustratingly onedimensional, depictions.

The veil may be the handiest, most unimaginative symbol of Arab femininity. UAE-based artist Lamya Gargash’s trio of video portraits of women wearing the black abayas preferred in the Gulf took on the associated clichés. Working from neutral raw footage, short loops of her subjects posing against a nondescript backdrop, Gargash digitally dissected each image, excising the exposed face and hands from the folds of the abaya. In the final works, each separated element played on half of a split screen. Isolated in white fields, the surreal, floating faces and hands forced the viewer to register the unique expressions and gestures of each subject. Izdihar (2007), young, pretty, preened coquettishly, repeatedly adjusting her scarf for maximum effect, while the older Lee (2007), serene and composed, barely moved, holding her hijab firmly in place. Reducing the female body to a disembodied mask, these videos seemed to support psychoanalyst Joan Rivière’s famous assertion that femininity is inherently a masquerade. Alternately, the animate but empty black shells looked positively spectral, phantom reminders of the quiet violence of stereotypes.

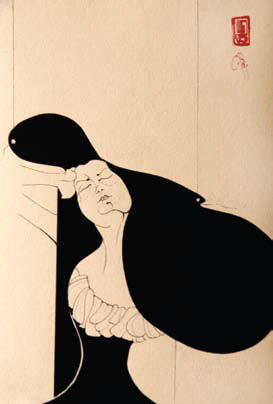

Hayv Kahraman’s precious Matrioshka (2007) sculptures provided a more humorous take on the veil, adapting the traditional Russian nested doll for the Middle East. Smooth, shiny, and black, the outermost doll was a burqa-covered woman with a golden grille, at eye level. With each nested doll, the underlying figure was gradually exposed, finally revealing a golden-haired woman in an off-the-shoulder dress. Accompanying the sculptures was a (somewhat overwhelming) selection of Kahraman’s trademark sumi-ink paintings, some augmented by acrylic and watercolor, which drew from Japanese and Chinese art, Persian miniatures, and the melancholic yet exuberant art nouveau illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley, to explore diverse subject matter to varying effect. Many addressed the oppression of women in the Middle East, especially under war conditions, as in Kahraman’s native Iraq. Trains of captive women appeared in Kurdish Women Dancing (2006), Chained Women (2006), and In Line (2007), where the bodies were largely reduced to irregular, oblong forms, mimicking the dolls. In Honor Killings (2006), repeated sets of minimal forms depicted a dozen veiled women dangling by their necks from the branches of a barren tree. Strangely auto-Orientalizing, the skillful execution and formal elegance of these works seemed to grate against the ideological weight of their subject matter.

Refreshingly, Ghadah Alkandari sidestepped much of this prickly terrain in her quirky line drawings and colorful paintings, which featured a cast of dour-faced women, each sporting an austere bob. Writ large in Kahraman’s paintings, women’s oppression was more insidious in Alkandari’s drawings, hidden in quiet hysteria. Sometimes accompanied by text, each drawing was a vignette from the humdrum life of a housewife. An oppressive, almost palpable, ennui pervaded these scenes, which seemed stuck in the interminable moment before something happens: before the door is answered, in The Door I-III (all 2007), or before a rival is struck, in The Slap (2007). In Feeling Pretty (2007), the never-ending quest for beauty was a fraught balancing act, the protagonist teetering on one big toe atop a slender Vimto bottle. The Rehab (2007) showed a quartet of women with shopping bags, the title suggesting that shopping might be both cure for and symptom of their ills. Read against the backdrop of Dubai’s fashion-crazy mall culture, Alkandari’s wry drawings seemed to question the emancipatory claims of the modern Gulf woman.

While distinct in media and affect, Neda Hadizadeh’s expressionist canvases — attempts to capture the frustration and angst of her fellow denizens of Tehran in paint — resonated unexpectedly with the other works. In Untitled (10) (2007), the figure was fragmented and reduced to its most expressive elements, its eyes and hands, in extreme close-up, painted in thick black brushstrokes against a yellow background. Untitled (19) (2007) adopted a somewhat different approach; twisted figures were sketched in quivering white lines against black backgrounds, occasionally obscured by overlaid patches of color. Struggling to emerge into view, the body seemed to resist resolution, remaining unformed. Indeed, even the gender of Hadizadeh’s subjects was inconclusive. Not unlike the other works in the exhibition, her figures seemed to embody and express a poetic uncertainty and, finally, a subtle resistance to the neat, essentialized confines of stereotype.