Anna Boghiguian and Robert Shapazian first met in 2003 on Anna’s rooftop, brought together by a mutual friend who thought something might resonate between the two, at the very least a bit of mutual Armenian love. They clicked, one might say, in an unlikely fashion, and thus began Robert’s more than occasional trips from Beverly Hills to Cairo, as well as a correspondence that spans phone lines, email, and encounters such as this one.

Boghiguian is an artist. Born in Cairo in 1946, she studied political science at the American University in Cairo, and later received a BFA in visual arts and music from Concordia University, Montreal. She has illustrated many books, including editions of poems by Constantine Cavafy and Carnet Egyptien by Giuseppe Ungaretti for Fata Morgana, which also published her own book, Images of the Nile (2000). Most recently, she showed her drawings as part of Catherine David’s “Contemporary Arab Representations” program. In 2003, the American University in Cairo Press published Anna’s Egypt, a compilation of her drawings, paintings, and writings.

Shapazian was the founding director of the Gagosian Gallery in Los Angeles, where he worked for ten years. Prior to Gagosian, he was the director of the Lapis Press for eight years, a prize-winning book publishing company owned by the artist Sam Francis. He serves on the Photographic Committee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and studied English literature at Harvard.

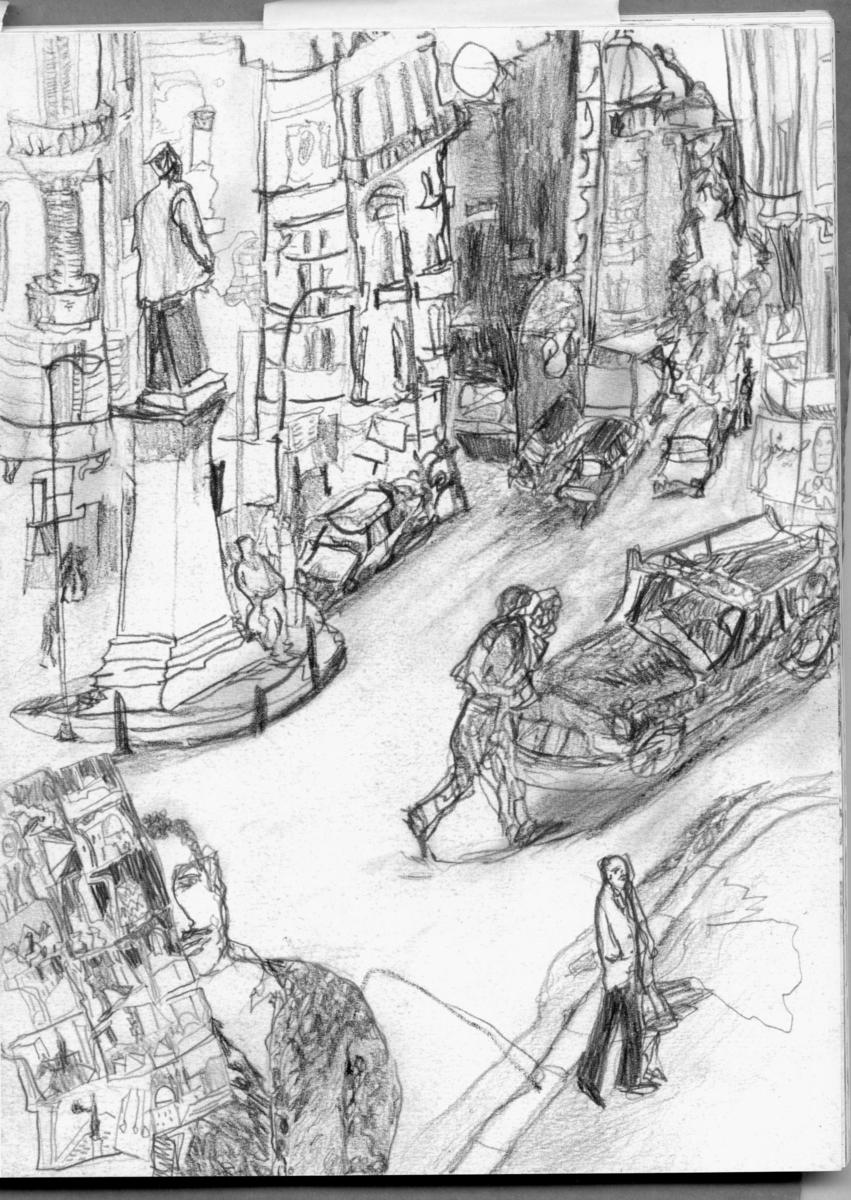

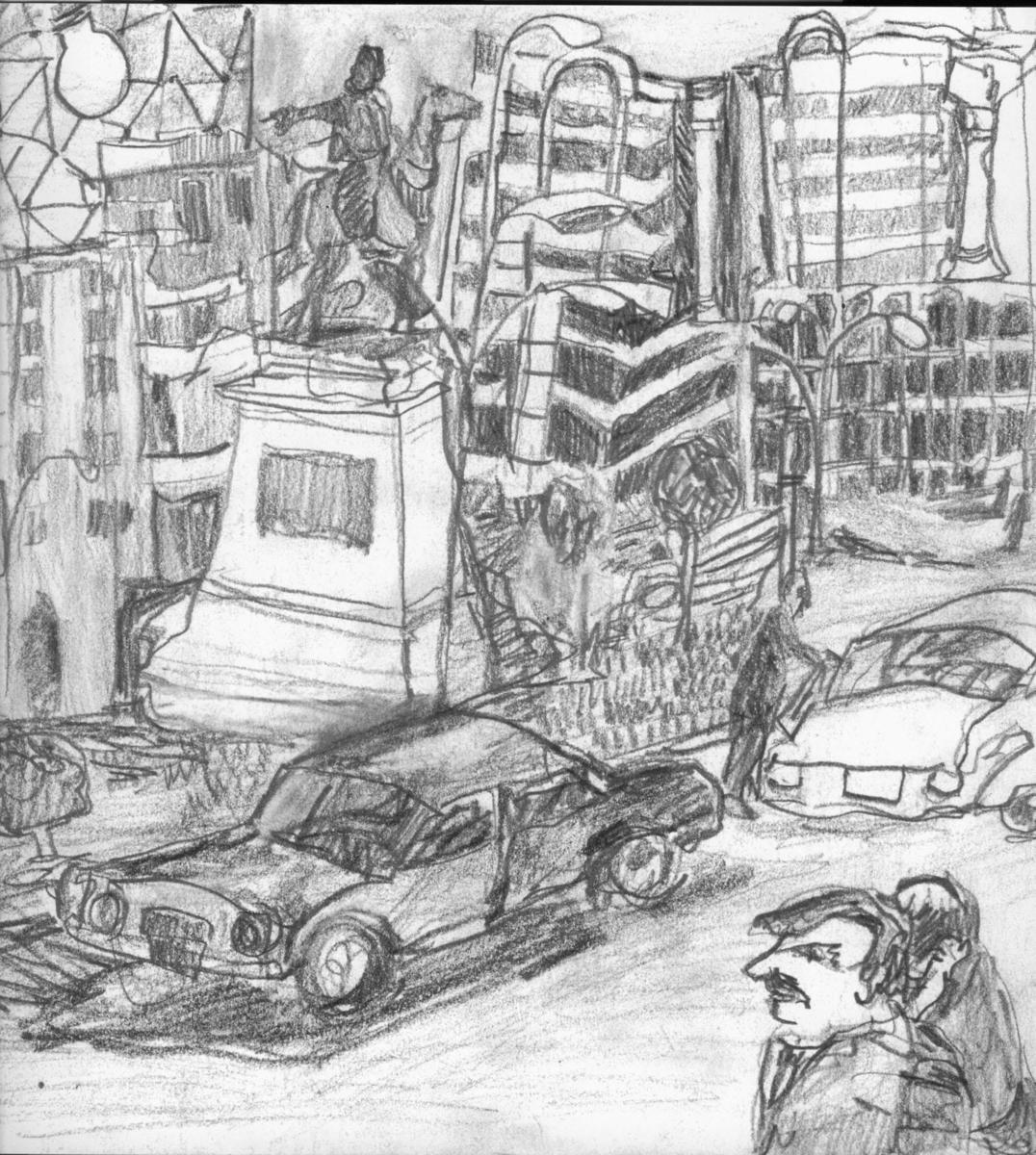

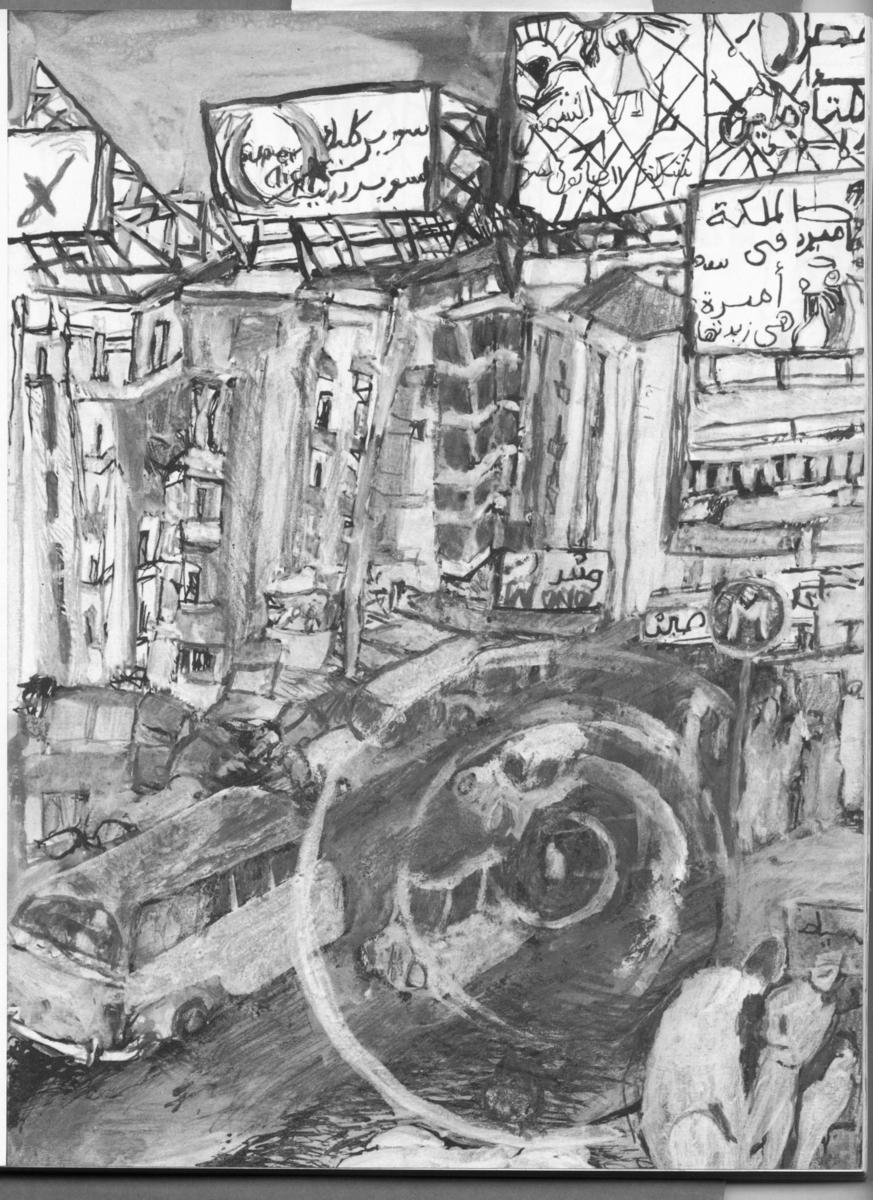

Robert Shapazian: Well, Anna, here we are at your studio in Cairo, on the roof of an old building on an island in the middle of the Nile, with Cairo old and new spread 360 degrees around us. It’s a dazzling and dizzying site. And it feels like the density and vertigo in your very great drawings and paintings of the city.

Anna Boghiguian: To me, it’s not just a place on top of the building, but it becomes a place that floats in the air. I suppose it’s very good to breathe the air of Cairo, to view Cairo from the top, and to listen to the sounds. You see certain episodes of situations that you do not normally see, like camels moving early in the morning, buffaloes, couples kissing each other, boys swimming naked in the river, young boys polishing their Reeboks, or I don’t know what expensive tennis shoes, in the river while they are dressed in rags. And they polish and they polish and they polish like a Greek god. It’s extraordinary to see Cairo at five, six, seven o’clock in the morning. The way I paint, sometimes I feel that my vision or what I put on my canvas doesn’t convey all the experiences I have lived through in this city.

RS: Now, let’s face it — you aren’t the most ambitious artist. You don’t spend a lot of time making art. Instead, you spend a lot of time procrastinating, walking around Cairo, and traveling to foreign countries. You certainly aren’t one of those artists who reports in at eight o’clock every day and leaves at five o’clock. What is it that finally compels you to pick up a pencil or pen and make an image?

AB: There was a time when I used to draw and paint twenty hours a day. If I traveled or was in a hotel or in a city, I always went with my paper and my pencil, and I couldn’t let it go. It’s only in the past six years that I don’t work so much. But I still work seven hours a day. I work according to my needs. You see, I don’t start working when I wake up, but I wait until seven or eight o’clock at night and then work until three. Or suddenly I’ll start painting every day, but then I won’t paint for a week. It depends.

RS: And what brings you to the point where you decide to make an image?

AB: I don’t know. It becomes very automatic. You see, I don’t think at all. But I do think when I don’t want to paint.

RS: [Laughter] Oh, you think when you don’t want to paint. So you have this idea, “I don’t want to paint anymore.”

AB: Yes, I don’t want to paint because I want to rest. I think that resting is very important. But I’m beginning to realize that this resting includes socialization. And so you become more of a nervous wreck. Because when you socialize with people, you have to give them something. And whatever you give, it’s never satisfying.

RS: To them or to you?

AB: To them. I think this comes from their childhoods when their mothers may have put their diapers on too tightly or too loose. This has made most people very irritable. They want things to be done in particular ways. “You know the way it has to be. You didn’t give me enough.” I think it all may come from a simple thing like a diaper not being properly fitted. So I find socializing very difficult. I mean, it may be my own great difficulty, but I find relating very difficult. Especially in Cairo.

RS: But on the other hand you’re extremely sociable. When we go around Cairo, you’re always striking up a conversation with somebody. You’re very spontaneous and curious, and you get into conversations. But you have a side that’s also a little reclusive. You travel by yourself, you work by yourself. Art is a lone pursuit. So this is something of a—

AB: —contrast.

RS: Right, a contrast. And of course, this is very alive in your art. How do you view your drawings and paintings in relation to the life around you that you live and see in Cairo?

AB: Some of the experiences come directly from my experience and some do not. I throw some away because I find that sometimes a social immaturity comes through in my hand. Cairo is a place of great contrast and confusion, and this is why—

RS: And the traffic. You said, to you, Cairo is all about traffic.

AB: Yes, there is a stream of consciousness going through Cairo, with all the cars and all the movement. It’s the motion of Cairo, this mentality of the Cairenes to own a car and to run around. Even if the car is completely falling apart and rusted, as most of them are, they still go around, and you don’t know where it will end. I draw a lot of cars, and I think this concept of the Egyptian mind and its mobility is a very interesting thing. Given the freedom, Egypt would be a very mobile nation.

RS: This multiplicity, of layers and confusion, is very present in your art, especially in your drawings. So many of your works look down into the vortex of the city, where things are moving and churning, like rushing water churning around a drain.

AB: Yes, it does have this aspect because of the movement. Maybe I haven’t been able to show it, but it’s the concept of motion, and motion is necessary. But as the motion in the country is confused, it can only rise up as vertigo.

RS: And what about smoking? You said you wanted to talk about smoking. How does smoking fit into the vortex and the floating and the—

AB: I think that my cigarette smoking is very upsetting to people. In Canada, it was very upsetting. But here in Egypt, yes, it’s okay, and in Paris and Italy it’s tolerated. I find my smoking has something to do with the dirtiness in my work. Like the cigarette comes, the butt falls in, part of the cigarette paper gets stuck on the paper and things like that. I’m a dirty smoker. There are clean smokers and dirty smokers.

RS: But this is something I have always thought very important, very unique about your work. It always has a quality of crumpledness or darkness or grime. Many times you can’t tell the difference between the graphite of the pencil and some random mark or smudge. You’re not sure if that’s the smudge of the pencil or if the drawing just got dirty.

AB: I think the drawing just got dirty. [Laughter]

RS: But of course, you allow this, you allow it to happen.

AB: I like the fact that they get walked on. I walk on them. They start having this quality of dirtiness. I think that if you make drawings too precious, it stops. If it’s too neat or too clean, of course, it becomes really pleasant to the eye to look at, and most of the people who look at this work are very clean people. I mean nobody who is filthy goes to a museum.

RS: Yes. It’s about cleanliness, order, clarity.

AB: Or usually they try to go to a gallery. You know, many people who are poor say they are always horrified to enter into an art gallery because they fear they’ll be looked down upon.

RS: Yes.

AB: I think it’s necessary to show we are doing art for the masses of the world, not for the one percent. But unfortunately, the thing one has to come to accept is, art is for the one percent. It’s only for the rich.

RS: But in a sense, I don’t think you feel very connected to that one percent.

AB: I think that I socialize with a lot of very rich people. And they are the type of people who seem to have problems with their diapers.

RS: The life that you’re leading is certainly not about the clean, polished, rich, getting-in-the-car-and-riding-around kind of thing.

AB: No, my socialization happens only by telephone.

RS: And often the way you dress and present yourself in public makes you look very eccentric. Rumpled and—

AB: I didn’t used to iron, but now I’ve taken to ironing my clothes.

RS: But somehow it doesn’t look ironed! [Laughter]

AB: It is ironed. It just comes from …does it look ironed? Look!

RS: Oh, I kind of see it now. Now let me also say that this dirtiness about the art, the smudge, the rumpledness, the—

AB: —it can also come from uncaringness.

RS: Uncaringness. That’s just what I was going to say. This quality is not at all premeditated in your work. It’s very natural, and it comes of its own self. A lot of times this dirtiness or somewhat derelict quality puts people off. One time I sent you to my friend at the New York Public Library to show him your extremely brilliant book about the world at the time of 9/11. I think that is a wonderful work of art, highly unconventional, and filled with life. I think it’s truly a work of genius.

AB: He told me it wasn’t well painted.

RS: Yes. So you went to the New York Public Library, you showed it to the curator, and he responded very negatively to these elements of, let us say, impurity.

AB: Yes.

RS: This quality work always reminds me of this very beautiful book by the Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows. There’s a portion in the book where he talks about the elegance and the beauty of grime. It is of the greatest elegance because it bears the marks of life acquired over time. Something old, or ancient, and yet shining from within. And I feel these qualities are very much in your work.

AB: Maybe. You know, I don’t give much thought to my work.

RS: Every time I come to Cairo, you’re always quizzing me about the art world.

AB: Yes, I find it very interesting.

RS: So what’s your relationship to the art industry, the galleries, and so forth?

AB: I’ll tell you. I find it’s like going to a free cinema, it’s like going to a free movie, it’s like going to a free Hollywood walk-around. It doesn’t have the glamour of Hollywood. It doesn’t have the glamour of anything. But it has all these people who seem like dolls, sitting behind desks and, usually, very well made up. They are usually dressed very expensively and usually they are very polite. And they usually look down at you. And I find that very interesting. And I find that it has some glamour, this thing.

RS: Does it? Is that glamour to you, a wish you could “get in”?

AB: No, I don’t wish to be them at all. When I talk and ask questions, the question of glamour comes to me because I find it very entertaining. I find the art world unreal and entertaining. I mean, I think the whole tragedy about the world of art is that it doesn’t deal with art. And this is extraordinary. It doesn’t deal with culture, and it doesn’t deal with humanity. It deals with neatness, cleanliness, conformism, and it says some technical things of complete unimportance.

RS: Now, you said you wanted to talk about money.

AB: Well, I said that I’m very interested in money, though at one time I thought it was unnecessary to make money. I suppose living in Canada makes you think that art should be for free. Who you are to ask for such sums of money? And of course, now this concept that you belong to the market to have a price is appearing in Cairo. You have to belong to the art market. Well, I’ll tell you something. The only thing that matters to me is to have money. And, being an Armenian, money is very important. Armenia as a nation, rootless for decades, has developed a sense that money gives protection, that it’s a wall of protection. This is true for many displaced persons.

RS: You’re not somebody who saves a lot of money, you’re not greedy, and you don’t make a lot of artwork to sell. You don’t really talk about money as it pertains to you. The only thing is that money gives you the ability to do certain things, like travel.

AB: I do need my money to travel. If I didn’t have money, it might upset me, but not terribly, because I would find another way of doing things like I did earlier when I didn’t have any. But now I’m old and it’s more difficult because you become tired more easily. Society won’t tolerate an old woman sitting on a sidewalk drinking a Coca-Cola. When you’re twenty, twenty-five, and you’re drinking Coca-Cola on the sidewalk, they say, “She’s having a good time.” When you’re sixty and they see your white hair, they say, “This one didn’t do anything with her life.”

RS: You do have a certain laziness about you. But you also are very engaged. You talk a lot, you’re looking around, you’re checking things out, and you’re going around the world. So there are these two things about you—

AB: I’m very lazy to get involved with people commercially. Because I—

RS: —and yet you have this professed love of money. Which you don’t actually have.

AB: I find it very difficult to socialize with art dealers, and I always feel that I have to go to their office and it has to click. And it never clicks.

RS: Why?

AB: I don’t know.

RS: Is it them or you?

AB: I think it’s them. Is that possible?

RS: I don’t know. All I know is that you and the life you lead are not one of high materialism. Every time we go out, you have a few pounds in your pocket that are all crumpled and dirty, and they fall on the sidewalk. In your mind somehow there’s a strong connection to money, but in reality it seems like there’s no connection to money.

AB: I have a lot of money in my pockets all the time.

RS: [Laughter] But it’s crumpled and dirty and only in little bills.

AB: The little bills fall out, but I usually have a lot of money.

RS: [Laughter] Oh yeah, oh, that came from another pocket. Right.

AB: I do think that I have some kind of attachment to money, and I also think that could spend $100,000 very quickly. I could spend half a million and be poor again. But I haven’t figured out what the measure of richness is.

RS: What does that mean?

AB: What does it mean to be poor, and what does it really mean to be rich? I think these things have to do with the capacity of the human mind and what it can do to achieve what you want it to do. You can get anything easily if you’re destined to do what you want to do.

RS: How do you feel about yourself and what you want to be doing? To be getting what you want out of life?

AB: Well, I think that I’ve gotten some things that I’ve wanted out of life. I’ve gotten things that I wanted to get.

RS: Last time I was in Cairo, I was at this point in my life where I was very confused and everything was in chaos. We were in a taxi cab riding through a lot of traffic, and I asked you, “What are we supposed to be doing in life? I don’t get it. Have you figured it out?” And you looked through the windshield and said, “Well, you know, in the last analysis, I feel one should try to be as noble as possible. You know, it’s not easy to be noble.”

AB: “Being a human being.” Someone who loves people, human life. And the Dali Llama, who said it’s very important to be a good human being. But I suppose many people find me an atrociously horrible human being.

RS: In what way?

AB: You’ll have to ask some of them.

RS: You told me once that you were most fascinated by this quality of something mysterious at the core of life.

AB: Yes, there’s something very mysterious at the core of life. I began to realize when I was young that there is a great mystery which is also associated with a great fear in life. I suppose when life becomes familiar, and you become more knowledgeable, the fear about human existence fades away and life becomes much easier to deal with. The mystery starts unfolding from vagueness to clarity, from obscurity to clarity.

RS: You told me you felt that as you got older—

AB: —it becomes demystified.

RS: How do you capture this in your work? I feel it strongly in your paintings and drawings, but how do you actually try to accomplish it?

AB: I would like to use more texture, first of all. Except for those paintings in which I use wax, there isn’t enough texture in my work. I use wax because in my mind, it’s related to candles, and candles are what you offer to shrines in churches. They become part of an offering to divinity. Using wax creates a type of union with something ephemeral and at the same time divine. It becomes luminous.

RS: When you look at so much of the art that’s made today and that makes it into primary public view in the art industry, the publications, all the things propelled by high culture, do you see much of this luminousness, or the essential qualities that you personally so value?

AB: I think that some of the young artists who have become famous in the past twenty years had that essence in the first decade of their work. But eventually they became merely technically proficient and started catering to the needs of the few.

RS: And why do you think this is?

AB: Because I think they socialize with the few. Their realities become linked with the reality of the few. If I’m not mistaken, to be elitist means that you become so separate from the human tragedy that the reality of human struggle fades away and another layer of artificial reality is built up. The greatest art touches the most people.