Just a crushed red box, another and then another, an ordinary companion always in the pocket or under a pile of papers unless desire is aroused.

The box contains flat cigarettes made from a cheap brand of tobacco, harvested who knows where, cultivated and harvested by the oppressed wage earners of the world. The ritual is accomplished better with a match than a lighter, so the matchbox and the cigarettes go together. With this particular brand of Greek cigarettes, it was the color of the box and the woman in a circle at the center that really attracted my attention: the red is cadmium, with a slight orange reflection, which reminds me of sucking deep red oranges.

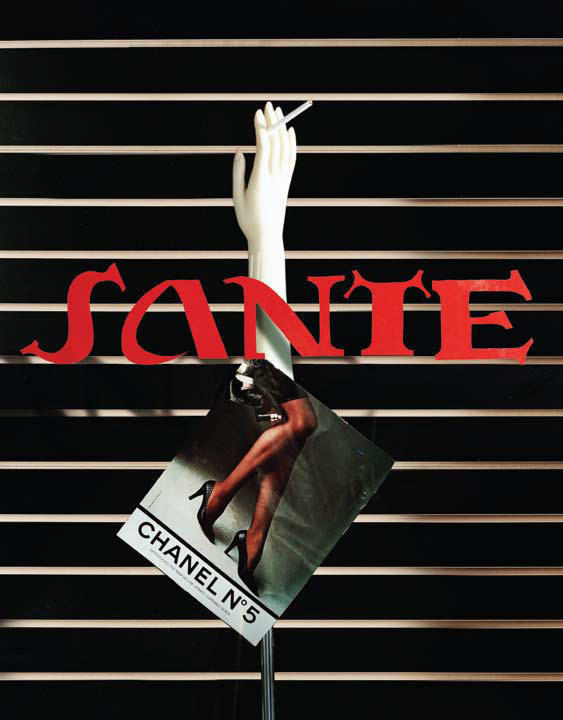

The cover lifts, and inside are the twenty-odd flat cigarettes. Up in the mountains of Crete a quarter-century ago, every peasant smoked this particular brand, so the taste and the smell of it lingered in the mouths of poor Greek villagers of that time, along with ouzo or homemade retsina. The blonde woman in the circle could have been Marlene Dietrich singing “The Blue Angel,” dangling her black-stockinged legs in the air, puffing a cigarette attached to her long cigarette holder. It could easily have been Renata Jordan of the Cairo-Berlin Gallery, who would assume from time to time the persona of Marlene Dietrich. Strangely enough, the heir to the tobacco company happened to be in Cairo for a while and befriended Renata, and together they would sing “The Blue Angel” in German. As time went on, they both died, but the little red box, like any other object, lingered on.

Gossip can sometimes be entertaining, and sometimes it can shed light on topics that are meant to be kept secret. The woman on the box had tinted blonde hair that is unlike but also like so many Greek blonde women. I was told she was the mother or the grandmother of the heir to the Greek tobacco company, but it was also said that this particular Greek woman was associated with Ataturk, a close friend or even his one-time mistress. It was easy to see her in the Dolmabahce Palace, in Ataturk’s bedroom, see her standing behind his white muslin curtains, singing love songs to the modern dictator, who had it in mind to throw a few thousand Greeks into the sea down by Izmir. It may even have been the whole city, as once when I strolled through Izmir I could only find the names of Greeks inscribed on walls of Greek-style architecture. Those who survived Ataturk had crossed over to the Greek islands, and as a memory of past days they had a little Greek red box with a Greek blonde woman.