Becoming Bucky Fuller

By Loretta Lorance

MIT Press, 2009

With his distinctive coke-bottle glasses, funny bow ties, tidy three-piece suits, and curiously progressive worldview, Buckminster Fuller appeared before appreciative countercultural audiences, offering, in the 1960s and ’70s, an alternative vision of peace, ecology, and leisure. Loretta Lorance’s admirably readable and generously illustrated Becoming Bucky Fuller looks back past this familiar chapter in Fuller’s long career to his earliest ventures as a young man on the make in the 1920s.

Fuller himself had an appealing, if enhanced, version of this chapter in his own self-myth. Thwarted in every visionary venture, near suicide, he rose from a dark pit of despair to dedicate his lifework to the betterment of humanity. Lorance, in a close reading of Fuller’s copious archives, reconstructs a more complicated story.

Fuller’s earliest years more closely resembled William Gaddis’s JR than Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. After being ousted from a successful business venture for the development, manufacture, and marketing of an innovatively better brick, Fuller designed and launched a series of business ventures dedicated to the development of an eccentric, patent-pending prefabricated house, promising, among other virtues, liberation from drudgery for the housewife, extinction of the mortgage system, and the end of alcohol consumption. Only after this venture stalled without witnessing the construction of a single house did Fuller advertise himself as a visionary — rather than admit a business failure, he simply declared that his project was at least twenty-five years ahead of its time.

Becoming Bucky Fuller will be of interest to Fuller fans, novices, and any general reader interested in the process of creative self-reinvention. For the newcomer, in particular, this appreciative but critical approach to Fuller’s early career will serve as an attractive starting point, far removed from the more familiar myth Fuller himself helped author.

My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness

By Adina Hoffman

Yale University Press, 2009

In the opening of My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness, Adina Hoffman presents a 1973 poem by Taha Muhammad Ali:

In his life / he neither wrote

nor read. /In his life he / didn’t

cut down a single tree, / didn’t

slit the throat / of a single calf. /

In his life he did not speak /

Of the New York Times /

behind its back…

In these pages, Hoffman provides an English-language biography of the quixotic Palestinian writer Taha Muhammad Ali, a figure who didn’t start writing until he was fifty-five. Some years ago, Hoffman, her husband, and a friend — a ragtag coalition of two Jews and a Muslim — started a small imprint, Ibis Editions, to publish English translations of Taha’s stories. Unlike other Palestinian poets we may know well, such as Mahmoud Darwish, Taha has never engaged in the “poetry of resistance.” He is by no means an exemplary national poet for the Palestinian people; his art is far more unsuspecting.

An underground autodidact, virtually unknown to Western and Eastern readers alike, Taha runs a souvenir shop in Nazareth that has, on occasion, been a gathering place for local intellectuals and artists. In these pages, Hoffman tells one man’s curious story, but at the same time, in her own way, manages to convey the remarkable power of poetry in the last century.

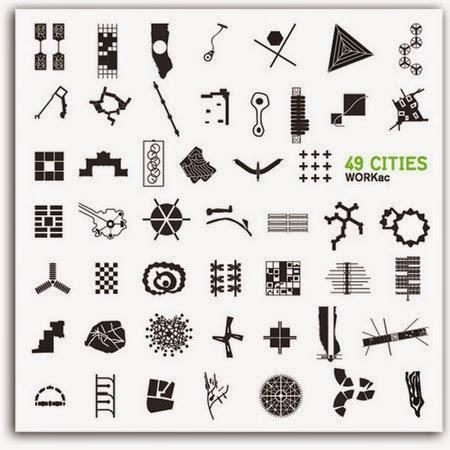

49 Cities

Work AC

Storefront Books, 2009

Published on the occasion of the Manhattan architecture firm’s eponymous exhibition at New York’s Storefront for Art and Architecture, 49 Cities compiles an encyclopedic range of visionary city plans from the past two thousand years into a slim, efficient workbook for today’s eco-minded urban planner. Arranged chronologically, the plans for fantastic, often radical, configurations of cities past — only a handful of which were actually built — are reexamined through a contemporary set of environmentally concerned, terrorism-obsessed criterion: form, density, greenspace, sprawl, foreign invasion, urban chaos, and air pollution. Plans range from Spanish conquistadores’ colonization of Santo Domingo (1650) to Baron Haussmann’s renovation of Paris (1850) to Rem Koolhaas’s conceptual Exodus project (1972), which proposed dividing London into “good” and “bad” halves, with a wall built around the good half as a contained zone for “architectural and social perfections.”

Work AC contends that the current crisis-state of natural resources and urban zones throughout the world finds planners and architects in a familiar position — constrained by fear and necessity to suspend disbelief and radically re-envision how to move ahead. Beyond updating each model with a strategy to consider current ecological concerns, the book contributes an indexical, accessible approach to a vast selection of plans, ideas, and ambitions, each notable for its grounding in its own time and connected here by its contemporary relevance to the challenges facing planners, builders, farmers, and city-dwellers everywhere.

A scale comparison at the front of the book is especially useful in gaining an understanding of ideas between forms. Through thumbnail simplifications, we see Arata Isozaki’s Cluster in the Air (1962), a plan for vertical public transportation “trees” and horizontal pedestrian path “branches,” which eventually multiply into a “forest” city, alongside Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s Salt Works (1775), a labor-supervision design for rationalizing industrial production informed by Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon. For all of the radial, clustered, and polyhedral plans included in 49 Cities, it’s the banality of Edgar Chambless’s Roadtown (1910), a linear city scheme of continuous development connecting Baltimore and Washington, DC, represented here as a single, barely bulging line, which in its similitude to the post-suburban status quo, seems to have been the book’s most prescient, if not most visionary, design.