Beirut

Video Works 2011

Metropolis Cinema

May 18-21, 2011

Five years after its founding in the aftermath of the 2006 war, Ashkal Alwan’s biennial Video Works program has emerged as an intriguing if also potentially misleading tool for measuring the evolution of experimental video in Beirut.

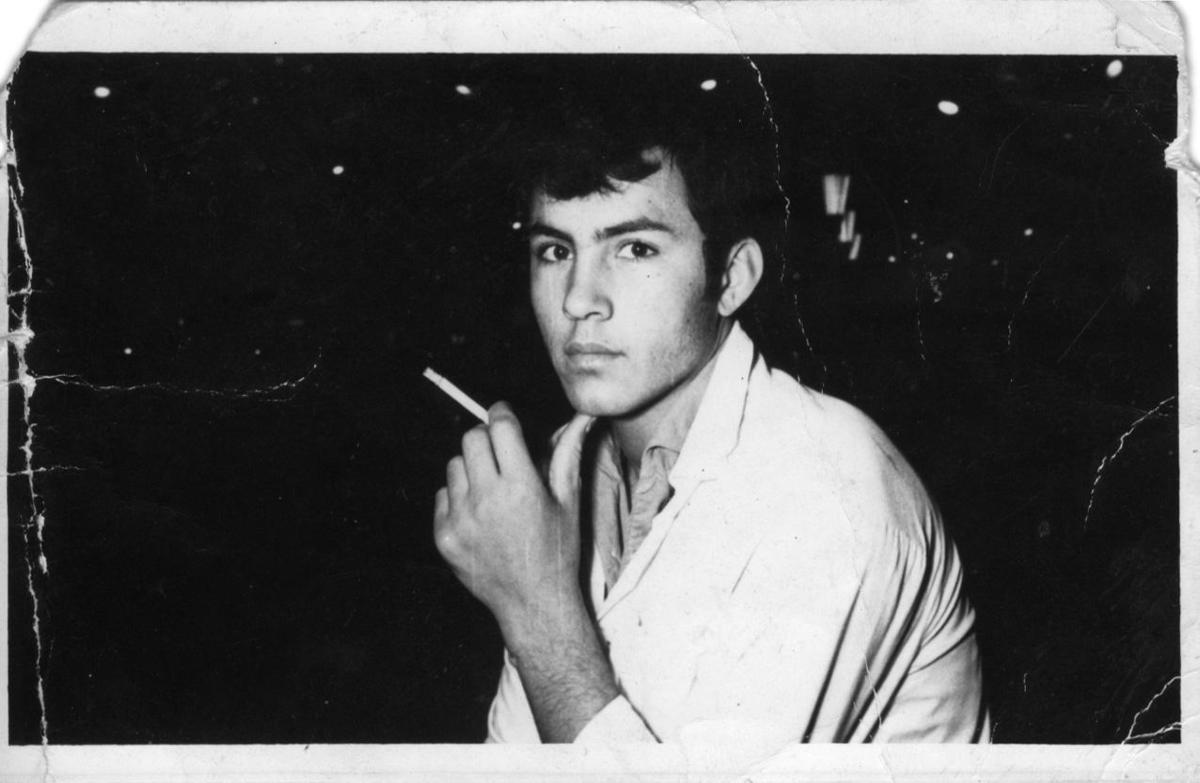

The Lebanese capital has been a critical incubator for the medium since the 1990s, when filmmakers such as Mohamed Soueid, Ghassan Salhab, and Akram Zaatari, among others, began messing around with an ever more flexible and unclassifiable form, sampling wildly from the conventions of television, cinema, social documentary, film essay, and more. In less than a decade, Beirut became known among international art circles as the go-to city for smart, searching, easily transportable works that dealt, more often than not or at least on the most superficial of levels, with crises of image and representation in the context of civil wars or other such traumas.

At a certain point, conflict-addled videos from Beirut — with their forgotten documents, faulty testimonies, hidden histories, buried sorrows, and increasingly thin memories of how things were before — grew so common that they verged on ossifying into art world cliché. It was time for something new, and it was also time to think about creating a kind of safe space for practitioners to pursue independent projects, without fear of failure or a coterie of international curators breathing down their necks.

Ashkal Alwan created Video Works as a means of building a sustainable support structure for young and emerging artists and filmmakers. It is less a biennial event in the biennial mode than the formalization of a creative process, running a proposed idea through the next logical stages of its development. The program consists of a cycle of production grants (awarded by a jury), an extended workshop (overseen by an advisor) and a public screening. In the Ashkal Alwan universe, Video Works isn’t a junior edition of the Home Works Forum, but rather a prototype for the Home Works Academy.

That the first edition, in the spring of 2007, ended up dealing with war all over again is one of the particular cruelties of living in Lebanon. But the third edition, in the spring of 2011, finalvly moved on to other anxieties, issues and enigmas. In past years, Video Works has played out like a handful of agonizing art school exercises. This time around, it maintained an ethic of incompleteness. By screening works in progress or testing out half-baked ideas, participants open themselves up to much-needed critical feedback. And of the seven works screened over three nights, several of them were clearly planting the seeds of feature-length films. But overall, the videos were far more polished and cinematic in style than they’ve ever been before. They were also far more enamored with sound, to the extent that pounding pianos and crackles of synthesized noise threatened to overpower the image time and time again.

Prologue, by the brother-and-sister team of Raed and Rania Rafei, is a 49-minute piece that takes as its starting point the student occupation of the American University of Beirut in 1974. Divided into three aesthetically distinct sections, the piece begins with a highly stylized sequence, as actors approach the camera one by one, literally coming into focus as they recall the day they took over the campus. The second part, shot with the amateur camera on a mobile phone, drops in on an exhausting and painfully claustrophobic meeting among the activists as they debate their options the day before the siege. The third part runs through a succession of archival images documenting the actual event.

The beauty of Prologue — which really is a prologue to a feature film that the directors hope to complete in the coming year — is that virtually all of the dialogue is improvised. The actors are young activists involved in Lebanon’s anti-sectarian movement. In addition to reenacting a late twentieth century event, they were asked to address themes of revolution and change, from their own twenty-first century perspective, just as the demonstrations in Tunisia and Egypt were gaining momentum. As such, Prologue blurs the lines between past and present, action and intention, experience, and ambition.

Whenever there is talk of video production in Beirut, someone inevitably invokes the idea of a generation killing its fathers. For the 1990s generation, there were no fathers to kill. For the current generation, the fathers are actually the artists of the 1990s generation, meaning people like Ghassan Salhab, who is, as it happens, the artistic director of Video Works. Salhab’s influence loomed quite large this time around, with at least three of the new works appearing to emulate Salhab’s most recent film, The Mountain.

But in many ways, The Mountain is itself an exercise in establishing and sustaining a mood, or in this case an atmosphere of extreme emotional tension. The film follows a man up a winding road to a hotel where he seals himself off from the world and slides ever more perilously off the rails. Tamara Stepanyan’s video February 19 likewise follows two strangers on a train. Their respective dispositions sink from the dull headache of preoccupation to the splayed limbs of total exasperation. The sexual energy becomes unbearable between them, and yet the most they share is a sidelong glance.

Both Wajdi Elian’s A Place To Go and Rami El Sabbagh’s The Last Hero concern men in suits with tedious day jobs who carry briefcases and look like something out of an advertising campaign for a menswear designer. While Sabbagh’s piece quickly veers off into schlock horror territory, Elian’s takes a surprisingly tender turn (and features a cameo by none other than Mohamed Soueid). But both works create moods of dark, dire, and ultimately insufferable alienation. Only Colin Whitaker’s Beirut Phantasy warms the mysteries of solitude, turning footage of two apartments (one wrecked, one restored) into a playful visual poem about the passage of time and love among the ruins of endless cycles of destruction and reconstruction.

If war memories were the first pitfall that too many emerging artists fell into, then pop culture mash-ups and edits of a family’s Super 8 footage are fast becoming the second and third. Both genres have yielded absolute masterpieces, but Roy Dib’s Under a Rainbow (made of deteriorated VHS footage of child stars, vulgar pop singers and a Bandaly family movie) and Cynthia Zaven’s Dear Victoria (weaving together her own material with that of her grandmother) could use a firmer sense of direction to take their ideas a little further.

Meanwhile, Alexandre Habib, known to virtually all as Siska, tries something else entirely. EDL stalks the sad state of affairs that is Electricité du Liban — arguably the most corrupt and decrepit public utility in Lebanon, housed in a building that once epitomized Mediterranean modernism but had since suffered from galling neglect — like a hunter-explorer in National Geographic mode. Ducked behind houses, crouched behind trees, he surveys the site from all possible angles. He also dissects the entire building floor by floor. The result is a work that actually documents a tremendous amount of detail concerning labor conditions in Lebanon. And that, most certainly, is a new direction for an art scene that has always been disturbingly indifferent to the lives of the working class.