In May 2004, India experienced a dramatic political transformation. The Hindu chauvinist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led coalition National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government was defeated and replaced by a Congress-led coalition, the United Progressive Alliance. Prior to the election, the BJP had been forecasting 300-plus seats. In the event, the BJP tally fell from 182 to 136, and the NDA fell dramatically from 320 to 189. Congress took 27 percent of the vote and the BJP 22 percent. The left gained their highest-ever representation — sixty-two seats in the Lok Sabha.

The most compelling way of accounting for that BJP defeat lies in a consideration of the conflict between image regimes. These image regimes are not concerned primarily with content and do not depend on the connection between iconography and the world. They are configured, rather, by a relationship between form and the world — a material dimension that operates in a longer durée.

I do not intend to argue that the 2004 elections are simply to be understood in terms of a mass sloughing-off of the aesthetic illusion of Adornoite schein in a vulgar Baudrillardian revelation of the disjunction between image and the real. The lifeless bright sameness of India under the NDA involved a quality of luminescence under the sign of “shininess” and “radiance.” Glossiness and shininess emerged as key concepts and terms in India in 2004. The ruling BJP coalition went to the polls in April/May 2004 with the slogan Bharat Uday, translated nationally into English as “India Shining.” They lost to a Congress coalition, one of whose prominent candidates, the recently deceased Sunil Dutt, claimed, “We are polishing the exterior, but the interior is starving.”

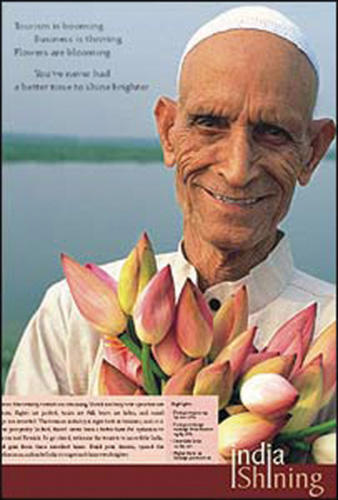

The campaign kicked off early (mid 2003) but surreptitiously, with the use of public funds to finance ostensibly non-political images: A middle-class woman plays cricket while her happy son skips on verdant grass; schoolchildren eagerly wait with their hands in the air, desperate to unburden themselves of all the useful information they have acquired; an elderly Muslim man holds a bunch of lotus buds in an ecumenical image of communal harmony alongside the caption:

Tourism is booming Business is thriving Flowers are blooming You’ve never had A better time to shine brighter

These pictures, the commentator Shiv Viswanathan observed in the journal Hinal, were part of a “semiotic warto redefine nation, state, history, economics, and geography”: They sidestepped the electoral liabilities of caste, religion and tradition in favor of a “supermarket of dreams and values…in virtual reality” and were accompanied with advertisers’ jingles:

Roads are lengthening Distances are shortening Bazaars are buzzing Schools are bustling Children are sparkling Future is inspiring.

The government claimed that it was justifiably using public funds to promote the state’s achievements, a view with which the Electoral Commission disagreed. Before the campaign was terminated at least sixty-five crore rupees (approximately fifteen million dollars, although according to some other estimates the campaign cost almost twice this) had been spent in one of the biggest media campaigns in India. Even mobile phone users found themselves bombarded with sixty-second messages from the prime minister reminding them that under the ruling coalition they had never had it so good.

The dual linguistic registers of “India Shining” and “Bharat Uday,” on the face of it, seemed a recognition that different constituencies required different codings and different metaphors. They attempted to invoke two quite different modalities of identification. This issue was explored by Sorab Mistry, the Southeast Asia area director of the transnational marketing group McCann Erickson, in a discussion of semantics and strategic marketing. Both “Bharat” and “India,” and “Uday” and “Shining,” signified different entities, he suggested.

“Bharat,” he argued, quoted on the website estrategicmarketing.com is “the mythical notion of India, once great and now believed to be in decline. ‘Uday’ points to its grand revival, its awakening, its rising to recapture its lost glory.” ‘India,’ by contrast, is the nation state, “modern and progressive,” and “Shining” is “the confirmation that what’s looking good in other peoples’ mirrors… Shining is here a sign for success, especially for material success. Nothing shines like new money. It in fact builds in the anticipated consumer reaction and plays it back to the consumer.”

Mistry suggests that the dual appeal of the linguistic registers should have been efficacious, for under the guise of a unified branding it in fact subtly addressed two different audiences with different codes. The failure of this strategy, he concludes, is due to the fact that both “Uday” and “Shining” lacked what he termed the “stickiness” of call signs such as “Free,” “Extra,” “Off ” and “Offer.”

Another critic neatly identified the dual constituencies of “India” and “Bharat” in the following way: “Maybe about four to five percent of people who live in ‘India’ may have something to feel good about. However, for the majority of population who lives in ‘Bharat,’ the good feeling seems to be virtual.” (Neeraj, India, on the BBC website)

“India” here signifies the nation state in a global economy, but “Bharat” fails to evoke the mythic homeland in a state of immanent rising and shining. “Bharat” rather signifies the territorialized economic predicament of a deterritorialized “India.”

The India Shining campaign, however, seemed to have no ability to flatter the masses on their own territory. The vulnerability of the campaign was dramatized in mid-April when twenty-one women died in a stampede at a BJP rally in Lucknow, Prime Minister Atul Behari Vaypayee’s Lok Sabha constituency. Initially this seemed like a small tragedy of the kind that appears every few weeks in the India press (“Sari dole in Vaypayee seat turns messy,” the Hindustan Times reported on April 13). But the symbolic potency of the event quickly became apparent.

The deaths occurred when organizers of a birthday celebration for Vajpayee’s election agent Lalji Tandon started to throw saris into the crowd and pandemonium broke out. It then became apparent that the women at this function, who had been bussed in from nearby slums in Khadra, Daliganj and Sitapur Road, had been forced to pay twenty rupees (about fifty cents) each for registration and transportation. In return for this, they were promised saris worth 500 rupees and a lavish lunch.

On April 15, three days after the tragedy, the Times of India ran a photograph of the mass cremations of the twenty-one under the Blakean headline “Shining, shining…burning bright.” The report by Atul Chandra observed, “When the rest of India is shining, here in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s constituency, 20,000 women were expected to gather in forty-one degrees Celsius heat for a free sari. These women, and lakhs [hundreds of thousands] of others, are hardly able to keep body and soul together. For them a free sari — so what if it was worth only forty or fifty rupees — would have helped cover their bodies. That twenty-one of them had to be wrapped in shrouds instead is another story.”

Just before the elections, I was struck time and time again at the depth of anger toward the ruling BJP state government (at that time led by the female ascetic Uma Bharati) and toward the national coalition. The incompetence of the state administration was a continual talking point, and the sign of this — which dominated everyone’s life — was the almost complete absence of electricity. District towns were allocated only six hours electricity, and villages two or three if they were lucky. Uma Bharati’s regime had complemented the national India Shining campaign with its own advertising jingle: kali raat biti, mehnat jiti (dark nights are over, hard work has paid off). But this was somewhat undercut by the fact that outside of the state capital of Bhopal, most cities and nearly all villages were in near-permanent states of darkness.

Increasing rural impoverishment has entailed an increasing dislocation of large parts of the population from the state utopia of a citizenry interlinked through technology. Two year ago in this central Indian village there was a satellite dish, leased by one of the village’s liquor dealers, who gave his sixteen subscribers thirty or forty television channels. But his subscribers were unable to pay, the dish was repossessed, and the dealer left the village. Villagers can, in the two or three hours when there is electricity, receive terrestrial television, but it is only one channel, and makes only ghostly appearances through blizzards of interference. Their India is not shining.

At a national level, the Indian National Congress response to the India Shining campaign that eventually emerged was a form of politique noire, a poster and advertising campaign that invoked an aesthetics of gritty black and white realism. However, in the early part of the campaign multicolored images predominated. Many depicted Sonia Gandhi (the Italian-born widow of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi and leader of the Congress) — as an embodiment of female solidarity (“After all, why are they afraid of a woman,” read one slogan) and as humble supplicant in the cause of national development (“Come let’s develop a great country, to build a new nation,” read another). Other colorful posters targeted specific constituencies (“Congress’s resolve. Prosperity for farmers. Rights for women. Education and employment for youth”). Some reworked the Nehruvian image of strength in diversity (“They only want their own progress / We want the progress of everyone,” which depicts Hindus, a Muslim, a Jain, a Buddhist hill person, and a Sikh).

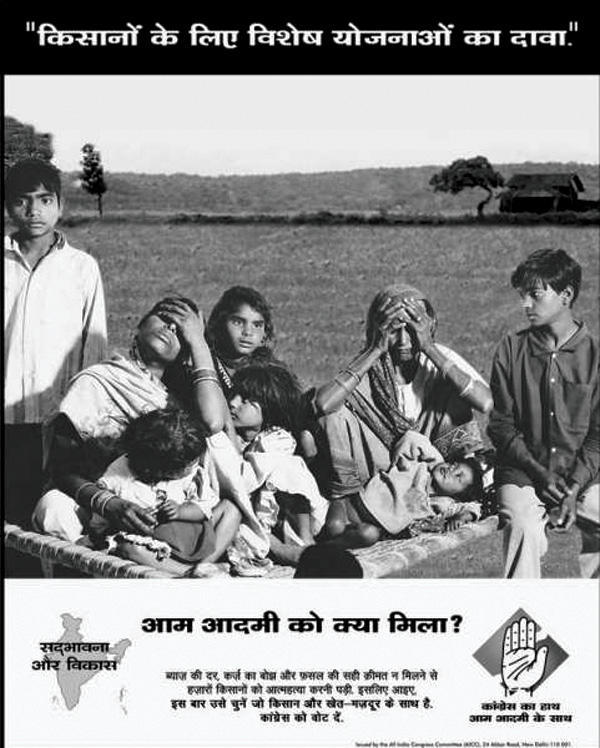

But a black and white campaign whose aesthetics were directly opposed to the colorful glossiness of the BJP campaign soon came to dominate. It targeted the rural and urban poor and unemployed youth. “Special development for farmers was promised,” ran one poster slogan above an image of a suffering peasant family sitting on a string charpai (cot). Beneath this ran the slogan repeated throughout all Congress images, Aam aadmi ko kya mila? (What has the common man gained?) Another black and white poster showed disconsolate youth queuing outside an Employment Exchange beneath the slogan, “Five Crore Jobs Were Promised” (5 karor rozgar dene ka dava).

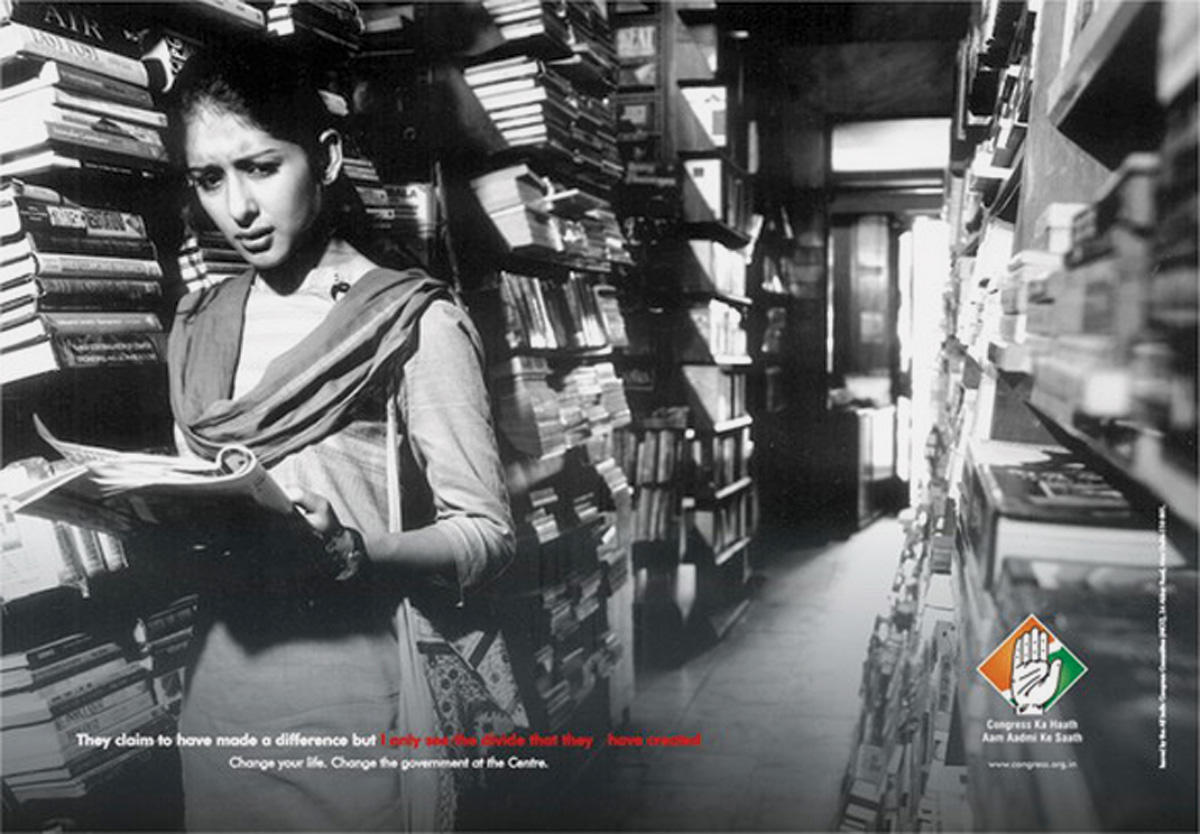

Congress’s English-language press campaign was pitched at the middle class: Double-page spreads — in the same politique noire aesthetic — dramatized the predicaments of more affluent citizens. A young female university student was shown in a secondhand bookstore, pondering, “They claim to have made a difference, but I can see only the divide that they have created.” A middle class father walks his uniformed child to school alongside the slogan, “They promised an education revolution, but my child is being taught distorted history at school” (a reference to the BJP’s rewriting of school history textbooks). This series of advertisements ran the central slogan in English and the campaign slogan Congress Ka Haath/Aam Aadmi ke Saath (The Congress Hand with the Common Man) in Hindi.

The Congress campaign, run by the advertising agency Leo Burnett, cleverly targeted two different groups: the poor who felt increasingly destitute, and the middle class who may have benefited from the NDA’s trickle-up policies but were uneasy about BJP ideology. This uneasiness was targeted in a poster with the slogan, “Before you vote for just one face, remember what comes along with it.” Vajpayee’s was shown as the central visage of the Hindu demon Ravan, on either side of which extended faces of various extreme members of the “Sangh Parivar,” the network of Hindu groups with which the BJP is in dialogue. Vajpayee was very much the presidential and respectable face of the BJP, in contrast to otherfigures such as Narendra Modi, the butcher of Gujarat, and Bal Thackeray, leader of Bombay’s extremist Shiv Sena. Congress thus broadened its constituency from the poor that had been targeted in previous campaigns to a more encompassing aam aadmi (common man).

Congress spent a paltry twenty crore rupees on their campaign, and between March 2 and May 10, 3,000 insertions appeared in the press, eighty percent of them significantly in the regional press. According to advertising industry analysis, “the entire campaign was conceived in Hindi and regional languages,” and different images were shot for different regions with regionally specific models, (see www.magindia.com).

It seems clear that “India Shining” was not simply a slogan that backfired. Rather, it dramatized point of rupture within neoliberalism. Clearly this does not take place solely at the level of the image: At heart the 2004 election was a contest between rich and poor. But the image world is more than simply a superstructural irreality that ideologically mirrors infrastructural truths. Image worlds are intrinsically joined to the lifeworlds of different classes. The gloss of “India Shining” was an intrinsic constituent, a summation of what Adorno and Horkheimer called “the triumph of invested capital.” The visual starkness of Congress’ advertising engaged an aesthetic fundamental, the experience of poverty. The aesthetic contest was simultaneously a contest of lifeworlds and classes.

The Bay Area Situationalist Collective opened a recent treatise — which makes a compelling case for the usefulness of Debord in understanding the contemporary American state — by describing the moment in February 2003 when the tapestry copy of Picasso’s Guernica hanging in the anteroom of the UN Security Council Chamber was curtained off at the insistence of the US. It was deemed inappropriate as a visual backdrop for pronouncements on the virtue of the aerial bombardment of civilian populations in Iraq. The reason for all this anxious Velcro, the Situationist Collective concluded, was the state’s fear “that every last detail of the derealized decor it had built for its citizens had the potential, at a time of crisis, to turn utterly against it.” It was perhaps the iconographic nature of Guernica that allowed the US to recognize in advance the threat that it posed and hence to order its concealment. States have a well-developed sensitivity to the destabilizing potential of iconography. But as the 2004 Indian elections demonstrate, their ability to immunize themselves against catastrophic implosions at the level of aesthetics remains extremely limited.