I know kids who were traumatized for life by that scene at the end of Mary Poppins, where the old man at the bank floats up into the air and can’t be brought down again. I know others who to this day cannot bear to watch as Rolfe the Nazi rats out the Von Trapps hiding in the nunnery.

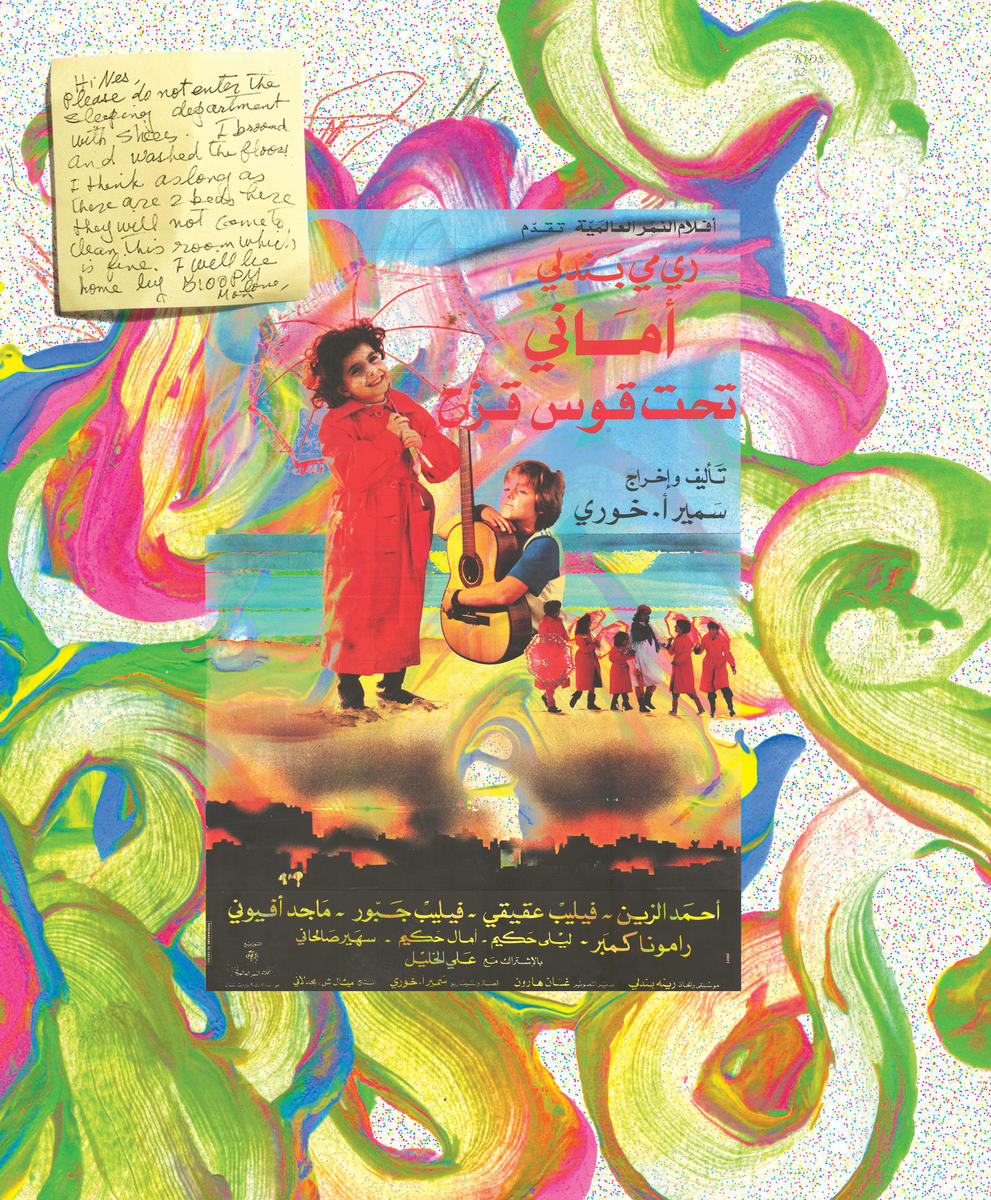

But for me, there is no cinematic trauma like the emotional ordeal that is Amani Tahta Qaws el Qozah (Amani Under the Rainbow), a Lebanese movie musical starring children, made for children, and yet so preposterously unsuitable for children in delivery, form, and content that it would almost be funny. That is, if it weren’t so impossibly sad.

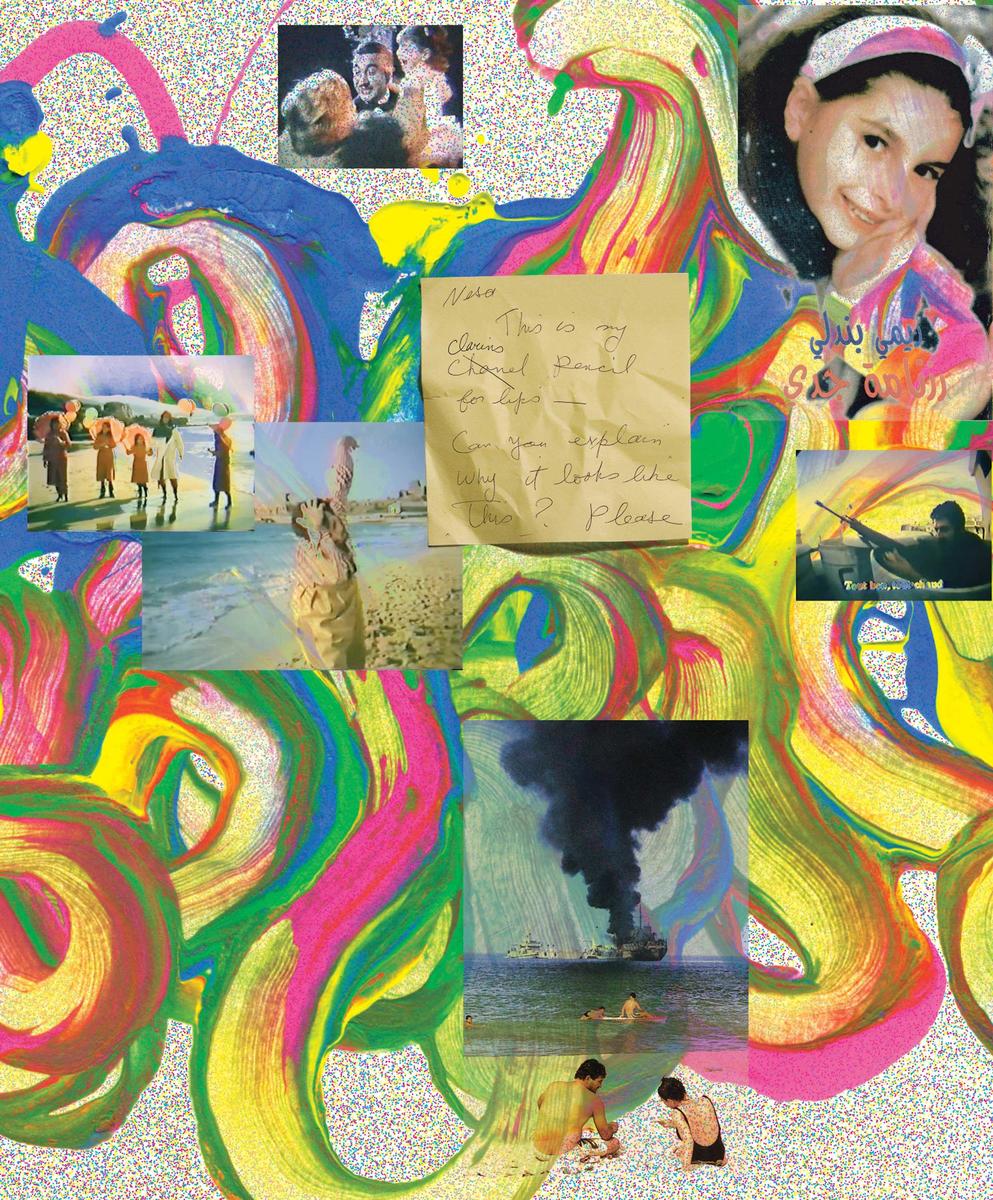

This is how it begins: we are in an idyllic village, where farmers farm, hens lay eggs, neighbors are friendly, and trees bear abundant fruit. Inside a lovely stone house, Mother Nadeeya is in the living room with her kids — dreamy-eyed and feather-haired Nabil and the tiny, buck-toothed Amani. Mom plunks out a tune on the piano, her shoulder pads moving up and down in time with the music; the pet sheep curled up on the rug listens patiently. Nabil strums on his guitar, his huge eyes the color of old bruises, and Amani sings in her tiny voice. There is a lot of congratulating of Amani, squeezing her and passing her from hand to hand like a parcel. The music is haunting and repetitive — disturbing, even. It’s appropriate enough, though, when you find out what comes next.

This is how the scene ends: Daddy comes home, speeding in his dilapidated convertible jeep. He tells the family about his day. There is more cuddling of the endlessly laughing Amani, while Nabil sulks jealously in the corner. Eventually Nabil is won over, and the whole family engages in much laughter and kissing and singing and the playful tossing of oranges and declarations of love. Then the bombing begins.

Laughter turns to screaming as the room goes dark and the only illumination comes from fires outside. The family runs to what seems to be the wine cellar, dodging bullets and shrapnel on the way. Nabil and Amani whimper that they are afraid, and Father tells Nabil to “act like a man.” A bomb screams down from above, and a bunch of stones collapse on the huddled family. There are no cutaways, no subtle intimations of what may have happened. They are simply buried beneath a pile of rubble and dust.

The children moan and scream for their parents, but Mother is clearly limp and dead, and Father, after a few feeble attempts to grab for his children, collapses back into the rubble and stops moving. Nabil has a giant bloodstain down the front of his shirt, and he groans and curses fate. Some old neighbors, Umm Saad and Abu Saad, rush in and pick up the two children. Nabil is clearly too heavy for the ailing Abu Saad, so the old man drags the ten-year-old out of the wine cellar and into the fiery night. All this takes place in the first fifteen minutes of what may be the first — and, I sincerely hope, the last — children’s musical made about the Lebanese Civil War.

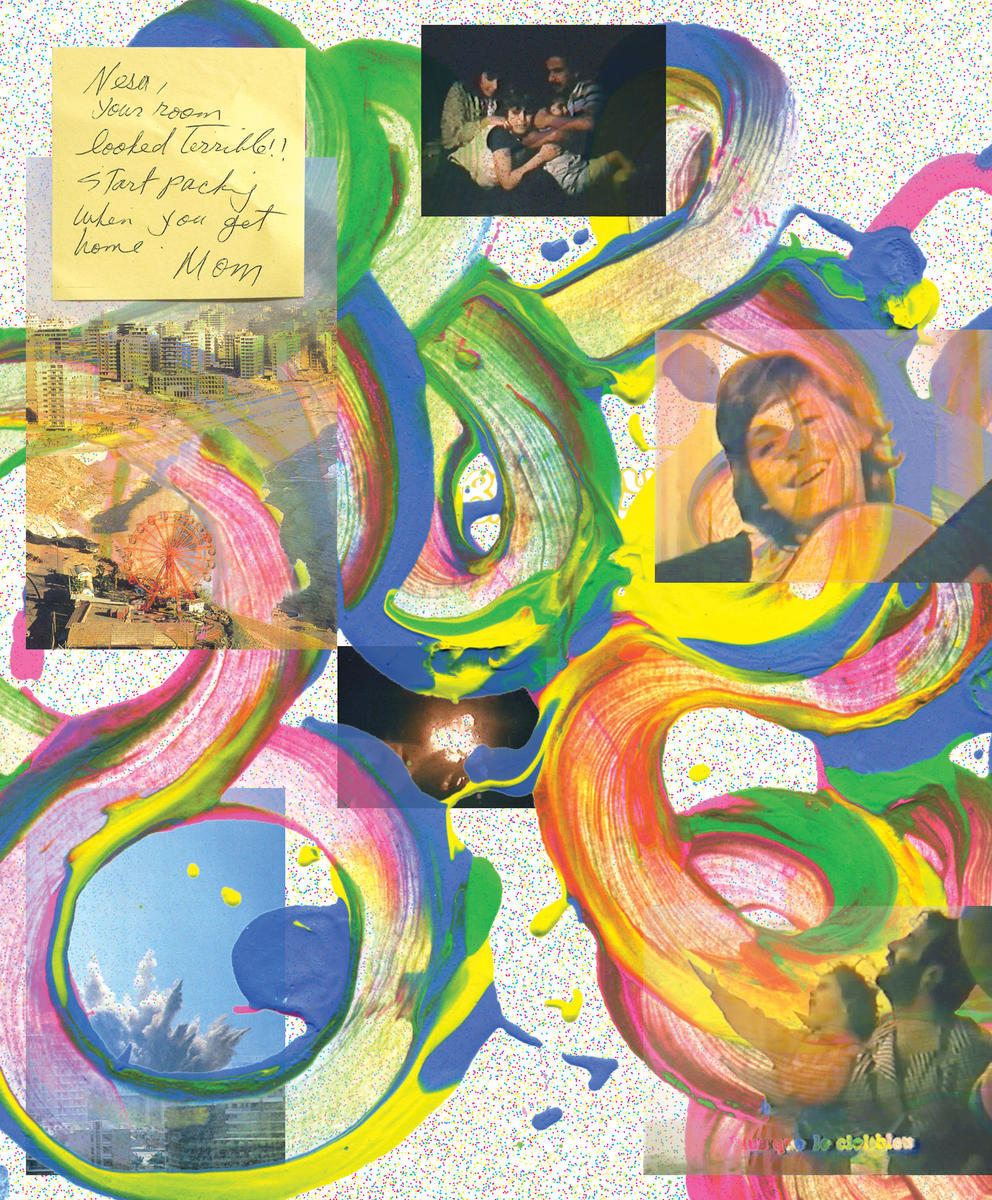

I grew up in Beirut in the 1980s, a time when the city’s name routinely evoked images of chaos and barbarity — hallmarks of our civil war. Strangely enough, though, I remember mine as a mostly idyllic childhood. The war was just another part of being a kid, like school and rain and doctor visits. It’s only when I look back at that time through my adult eyes that I understand how strange it all was.

A little like this movie, which I recently sat down to watch again, having not seen it for some twenty-odd years. It was during my early twenties that it really hit me that someone had actually made a musical for children about the civil war. I started asking Lebanese people of my generation whether they, too, had seen the movie. I misremembered the title as Amani Fawqa Qaws el Qozah (Amani Over the Rainbow), which seemed slightly more optimistic and also slightly more sinister than the real title. Mostly I would say, “You remember that movie, with the happy orphanage and the singing and the dancing when the parents get blown up right at the beginning?”

To my surprise, remarkably few people had seen it. Among those who had, everyone remembered the gruesome opening scene, though some memories were better than others. “Doesn’t the father’s leg fly off and land near the pet sheep?” one friend asked.

It doesn’t happen, the bit with the leg, but it might as well. For as I rediscovered, that opening scene is only the beginning of the horror show. There is far more shooting, more bombing, more fire, more parents dying in slow motion in front of their children than I had remembered. In between it all, children laugh and sing gaily through a series of choreographed musical numbers. That is, when they’re not sadly staring off into the distance, throwing temper tantrums, or thinking of their dead parents and lost villages. (I’m talking to you, Nabil, with your crazy eyes and hysterical weeping — didn’t you hear your dying father telling you to man up?)

Still, what I did remember of the film had mostly been happy. As a child, I watched it whenever it happened to be on television. I drove my parents crazy listening to the soundtrack at home and demanding it be played on every long drive. I loved listening to it most in the car: I would stare dreamily out the backseat window, barely registering the landscape rushing past, imagining I was the plucky, singing orphan Amani, hailed, cheered, and loved by all. It wasn’t so much that I wanted to be Amani as I wanted to be playing Amani — or rather, the girl playing Amani, child star Remi Bandaly.

Just as Shirley Temple stole Depression-era America’s heart with her lollipop-sweet blond curls and blue eyes, soothing the country’s sorrows over sugar rations and Prohibition, so Lebanon had Remi Bandaly as a symbol of lost innocence in the midst of an ugly civil war. The latest member of the Bandaly family (our very own singing and occasionally dancing multigenerational Partridge Family), Remi was born in 1979; she was a war child just like me, like everyone of my generation. The apocryphal story about her is that she was destined for music from the beginning, given her family history and named as she is after the second and third notes in the major scale (do-re-mi). At the age of six or seven, I guess I felt about her the way some preteens now feel about Hannah Montana. I owned her cassettes, I made my parents tape her televised concerts, and I forced my little brother to perform her songs with me. (Her younger brother played minor, supporting roles in her musical shows.)

On stage, she was a fragile thing in pastel tulle dresses that dwarfed her, struggling with a huge microphone and singing hits all penned by her generously bell-bottomed father, Rene Bandaly, one of which was a song that would become the definitive anti-war anthem of the Eighties, the trilingual “Atouna el Toufouli” (“Give Us a Chance” in English, although the literal translation of the Arabic words is “Give us our childhood”). Of course, when she sang the verse in English, she sang “Geev us a shaunce,” in that particularly Lebanese combination of elongated French vowels and eroded Arabic consonants.

Everything about Remi Bandaly was sweet: her accent; her squeaky munchkin voice; her strange, stiff dance movements; her rounded nose and chipmunk cheeks. I was a fan, but I was also secretly resentful of her. She was my first inkling of the alluring power of fame, how it casts a glamour upon those who wield it, obscuring their flaws and their humanity in the process, making them perfect and whole and revealing your own incompleteness as harshly as a bare light bulb in a dirty room. Remi was a better version of me. She was a better version of all us kids. When we refused to share, and whined and disappointed our parents, she was a perfect angel, selfless and patriotic, a national treasure.

I distinctly remember being in my grandmother’s house, in the damp, dark hallway where we hid from the shelling, listening to her plead, “I am a child with something to say, please listen to me. I am a child with something to say, why don’t you let me?” It seems so cheesy now, but at the time, she was speaking of me, for me, in the name of childhood itself, appealing to that unknown “they” causing the violence and the rift in our otherwise idyllic nation. I didn’t know who “they” were at the time. But in my head I could picture “them,” cartoonishly ugly and cruel. Their refusal to hear Remi’s heartfelt plea was the most glaring proof of their disregard for anything good in the world. They were surely men who kicked puppies, trampled on flowers, and hated children like us.

Amani Tahta Qaws el Qozah was released in 1983. That was the year after the Israeli invasion and siege of West Beirut, the year after the assassination of President Bashir Gemayel, and the year of the massacre of Palestinian civilians in the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps. It was the year of the suicide bombing at the American embassy and the ensuing evacuation of the American troops from Beirut. It was also the year I entered the first grade, just barely older than Remi Bandaly, and the year I remember being introduced to the idea of the Republic of Lebanon, rather than Lebanon, the place where I, my parents, and my little brother lived. At school, we learned about the colors of the flag, crayoning them in, trying to keep the tree trim and neat, trying not to bleed the border reds into the central white.

And Amani Tahta Qaws el Qozah was part of this rose-colored vision of Lebanon. This Lebanon was a unified, integrated whole, only waiting for the smoke to clear to rise and reveal itself. This Lebanon was packed with red-roofed mountain villages, with clear, running water and virgin-green, hand-pressed olive oil drizzled on fresh vegetables bursting with color. Where people were simple, their skin buffed to a healthy sheen — people who worked with their hands and kept their word. A world removed from the urbanized, big-haired and bushy-bearded, machine-gun-wielding villainous “them.”

Following the catastrophe of lost limbs and lost parents, we rejoin Nabil and Amani one year later, in the midst — of course — of another song. They’re in a classroom filled with other children, and their cheery singing informs us that they’re all orphans. The kids tell us what they want to be when they grow up. In keeping with the “village = good, city = bad” stance of the movie, the boys all want to be laborers. Nabil wants to go back to his village and become a farmer, Moussa wants to be a carpenter/plumber/car mechanic, another boy wants to be a baker like his dead father. (Later, in a flashback, we discover that the boy in question was riding in his father’s bread cart when his father was picked off by a sniper, who shot the father once, took a lazy bite of his sandwich, waited until the father had thrown his convulsing body onto his child to shield him, then shot him again and took another bite. You’d think that might be enough to turn you off bread for life.) The girls all want to be teachers. Amani, the littlest of them all, wants to be “a superstar… the greatest singer in all the world,” and somehow it is this dream, unique and impossible as it is, that we root for the most.

Eventually, we learn that Mama Salwa and Papa Sleiman, who look after them, can’t have kids and so consider these war orphans their own. Nabil, however, keeps turning his bruise-blue eyes to the distance and screwing his face up into a disfiguring smile of longing. He wants to go back to the village. During one scene, as the kids are being tucked into bed by Papa Sleiman, Nabil kicks up a fuss about wanting to see his parents again. Amani is then prompted to ask when they might be coming back. Papa Sleiman, in the magnanimous tone of the smug, all-knowing adult, tells her an outrageous lie: her parents have gone off to buy her some wonderful gifts. Nabil, trying to correct him, adds that these gifts are somewhere in the sky. Remembering this scene, it’s hard not to get angry, reminded as I am of every time some adult tried to pass off shelling and shooting during the war as “celebratory fireworks.”

Perhaps no suspension of common sense demanded by the film is as egregious as when, terrified by a round of Christmas Eve shelling which sees the entire household huddled into a back room of the villa, Amani is called upon to stand and sing the national anthem. She stands and sings in her sweet little voice, and soon everyone is standing and singing with her, and the sound of shelling fades somewhat into the background. There they all are, united and proud, as though heroically resisting an invading army — no better embodiment of the other outrageous lie told by adults: that of “the war of others on our soil.”

“No matter what they try to do to our country, we will come out victorious, because our weapon is love, and the purity in the eyes of our children.” So toasts Papa Sleiman at the beginning of that Christmas dinner, echoing the words of countless Lebanese politicians and warlords past and future. I’ve heard at least three public expressions of that sentiment this year alone.

But the movie itself was made for children, after all, and like all children’s movies, it has to have a happy ending. Of sorts. We learn that the children’s father didn’t actually die but is a triple amputee lamenting his sorry existence in a facility for the handicapped. After having given up on living and relinquished all claim to his children, he sees the children performing, Von Trapp–style, at a benefit for war victims, and pounds his one arm against his wheelchair in raucous applause. They are all united in the end, to live happily ever after.

I hadn’t thought of Remi Bandaly for a very long time until one day, abroad and terribly homesick, I searched YouTube for one of the songs from the movie (the one on the beach, in which Remi reassures a crazy man that she will build him sandcastles “as beautiful as Beirut”). I found other Remi songs instead, songs I hadn’t heard for years. And I spent an hour reading all the comments. All those children who’d grown up listening to Remi were now adults with kids of their own, some firmly established expats, some immigrants longing for home, all of them longing for the past. “Where is Remi now?” some asked. Others wanted to know where they could get a copy of Amani Tahta Qaws el Qozah. Several said that it was their favorite movie growing up, that they’d love to show it to their own children now, “so that,” as one person put it, “they would know how much we suffered.” Remi’s face, that perfect round button framed by giant puffed sleeves, stares back from the screen, frozen in time. “Atouna el Toufouli,” she sings. “Give us our childhood.”

In 1989, my family finally got the immigration visas we’d applied for, and we all moved to Montreal, Canada. I hated it there. Nothing reminded me of home, and worst of all, I didn’t know how even to begin to describe home to the strange new kids around me; they had such different points of reference, we might as well have been from different planets. I put away my Remi cassettes, my longing to be Remi. It all belonged to another place, another time. I no longer wanted to be a national treasure. I just wanted not to be noticed. I listened to Queen on my Walkman and waited for buses in the freezing cold like all the other kids at school.

But this year, startled at the passage of time and somehow nostalgic for the past, I started scouring the internet for anything I could find on Remi. What had happened to her? What did she look like? I discovered that she, too, had moved with her family to Montreal in 1989. It gave me a little chill to see how the same circumstances had uprooted us both and moved us to the same unfamiliar place. It didn’t matter that she’d been marketed as an anti-war icon by her savvy father — she too had gotten on a plane and emerged in a place where no one really gave a shit who she was, who she had been. And she too had had to learn how to stretch and mewl her French to be understood by the Quebecois. I thought I had it hard, trying to explain what it was to be a war refugee, but also not, also normal; I wondered what people said to her when she said, “I had a whole career before this. I was a child star in my country.”

Like a lot of immigrant families we knew, her family fell apart abroad. The reason Remi’s voice has fallen silent these days is because her father, in a fit of vindictive rage after a messy divorce, had a court order written up banning Remi from singing any of his songs. I learned that she doesn’t even have clean recordings of any of them, or complete footage from any of her stage shows. Remi’s career is as much a memory for her as it is for her fans. In fact, the only real footage of her singing on camera is in the movie Amani Tahta Qaws el Qozah.

She lives outside Lebanon still, having returned and then left again. When I wrote to her in September of this year to ask if I could interview her for this article, I was told she was too busy just then because she’s getting married. Or, as she put it, going through a “HUGE, LIFE-CHANGING EVENT” — could I wait until November? “If you’re not married,” she continued, “I hope it happens for you soon.” Except she used the Arabic expression for it, one I’ve been hearing a lot lately from relatives worried I might never settle down. I found it sweet and wonderful: Remi Bandaly, little Amani, was wishing me a happy ending.