Cairo

Invisible Publics

Townhouse Gallery

May 23–June 20, 2010

On the day this past August that Van Gogh’s Poppy Flowers (1887) was sliced out of its frame at the Mahmoud Khalil Museum in Cairo, setting off a cascade of political maneuverings and media recriminations (see The Artist-Bureaucrat Speaks), the museum had a grand total of eleven visitors. It was a detail that spoke to the concerns of an exhibition that had closed two months earlier at the Townhouse Gallery, Invisible Publics. Curated by Sarah Rifky, the exhibition took on the thorny issue of art audiences, placing the practices of viewing art and visiting art spaces at the forefront of the city’s multifaceted cultural sphere. It was notable for taking an informed stab at the issue of public engagement with the arts in Cairo and for its proposition of the art exhibition as a site where new publics might come into being. Indeed, the exhibition’s net effect was to demonstrate the circumstances in which Cairene publics do, in fact, coalesce around art events. However, it did not provide the basis for new registers of public engagement or a site for the appearance of new, even ephemeral, publics, as intended.

One work eclipsed the larger exhibition, becoming something of a media sensation and the target of state security censure. A performance by a group of enthusiastic, youngish, generally wholesome, and well-to-do men and women referred to as the “Cairo Complaints Choir” debuted at the exhibition to an audience of a few hundred people and no less than twelve TV cameras. An iteration of the ongoing Complaints Choir project initiated by Finnish artist duo Tellervo Kalleinen and Oliver Kochta Kalleinen, the choir comprised some twenty members who had gathered regularly over a series of weeks to compose and rehearse lyrics and music. Derived from the Finnish term “Valituskuoro… used to describe situations where a lot of people are complaining simultaneously,” according to their website, the piece is sincere and light-hearted, inviting groups of volunteers to transform their grumbles and gripes into lively vocal recitals. Meanwhile, the populist orientation, the activist undertones, and the emphasis on collective authorship and performance resonate with contemporary art world concerns.

The project’s manifestation in Cairo differed from earlier Complaints Choir performances in locations such as Helsinki, Hamburg, and St Petersburg. The music reflected local genres, and the complaints, strung into songs, seemed distinctly more aggrieved, with references to Egypt’s decades-long emergency law alongside comparatively niggling pleas for an end to the popular practice of pissing under bridges.

While rehearsing, the choir-group had promised to restrict their complaints to issues covered by local newspapers as a way of keeping the gallery out of trouble, a compromise that left open a respectably wide, if not unlimited, range of subjects. According to Townhouse director William Wells, a recent spate of lawyers’ protests set against the looming question of the aging President Mubarak’s successor had already led to heightened state security scrutiny of the gallery’s activities. While Rifky insisted that the intention behind the work was not political, it’s hard not to hear the ring of protest in lyrics such as: “The workers aren’t heard / Even the factory has been sold / The wheat is American / Our gas is being exported.” Nevertheless, it’s unclear whether the security forces to whom the gallery is obliged to report would have taken such offense if the media response had been different.

From the beginning, the Complaints Choir was the object of keen journalistic interest. The biggest source of official grief and embarrassment was a montage aired by Dream TV’s Mona Shazly on her daily hot-topic talk-show Al-Ashera Misaan (or 10PM), and combining footage of political demonstrations and domestic political scandals with footage of the Cairo Complaints Choir performance. The program’s immediate effect was to sensationalize the performance as raw political protest, leaving aside any consideration of the larger exhibition context. Under pressure, the Townhouse cancelled planned choir performances and dissuaded further media coverage.

This series of events seems to have been choreographed to demonstrate the principle that organized cultural activities in Egypt are tolerated to the extent that they remain irrelevant, that is, that they avoid acting as powerful catalysts for discussion through which new publics might actually emerge. Works that threaten to act precisely in the terms held up for examination by Invisible Publics are often abstracted from their art-world contexts, transformed into spectacular vehicles for broader debates, and censured.

It is not surprising then that a work of art gathering dust, unnoticed for days or decades even, might be described as perversely ideal. Should a public materialize around these works it would be at an infinitely smaller scale, conceivable first in terms of individuals rather than groups or interests. Both alternatives present their own distinct disadvantages. However, the dynamics of the latter are more difficult to articulate or even to conceive of clearly.

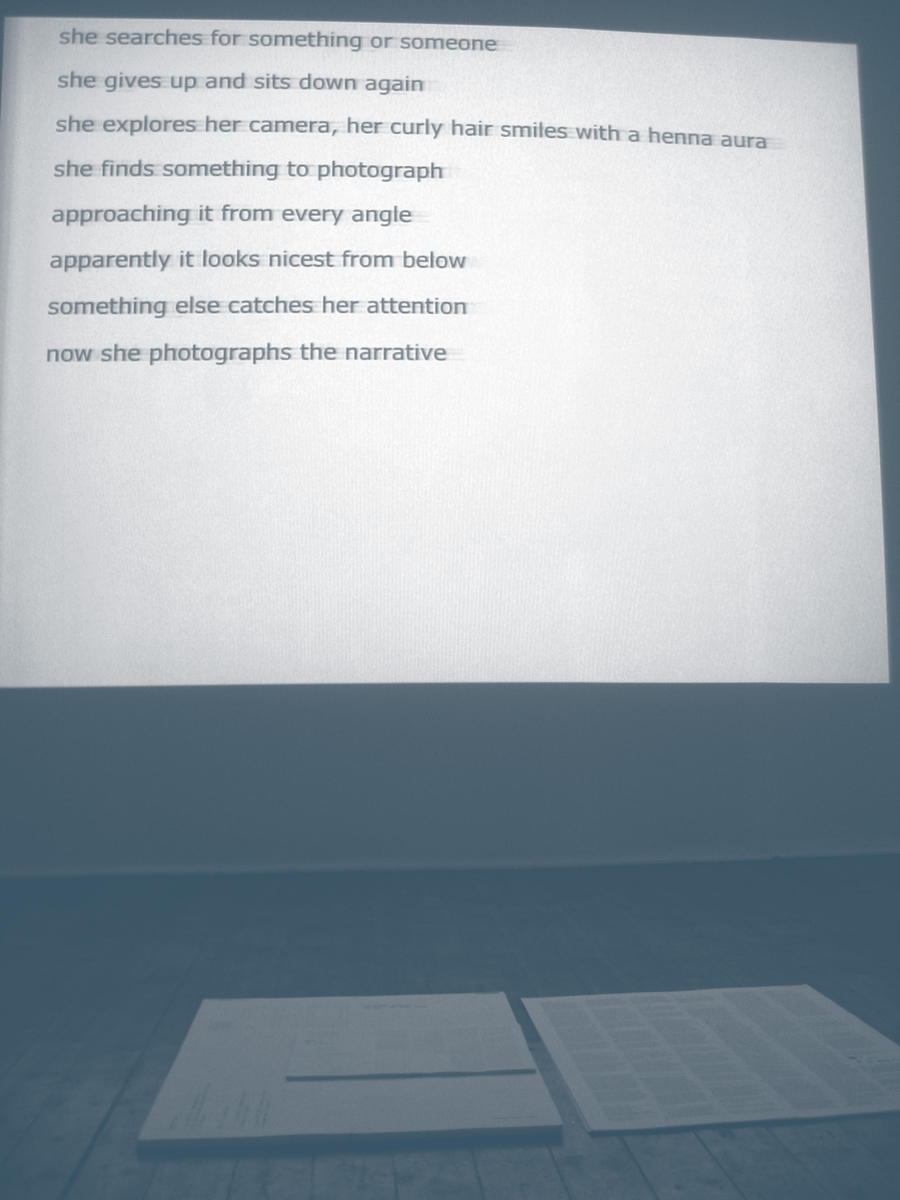

Some weeks after the fuss around the Cairo Complaints Choir had died down, the Townhouse hosted Instant Narrative, by Brussels-based artist Doris Garcia. The show spoke lucidly — in its own terms — to the curatorial project underlining the exhibition. Projected onto a back wall of the Townhouse was a live narrative of events taking place in the gallery, authored by a gallery staff-member sitting in another room but within eyeshot. At turns telegraphic and poetic, the narrative lasted for the duration of the show, continuing with or without the presence of visitors. It took a second to realize that I was in fact being written into the work, which acted effectively as a textual shadow of visitors’ movements and conversations. But once I had noticed, it was difficult not to experiment with intervening in this intimate record or attempting to drive forward the story (told only to me and a handful of other visitors) as a reflection, in a sense, of my own presence. This struck me as a fair approximation of the logic of the invisible public with which Cairo’s cultural institutions have been “communicating” for decades.