Friendship inflects and informs much of the artist Meriem Bennani’s work. Many of the actors in the films that comprise her dystopian science fictional film trilogy — Party on the CAPS (2018-19), Guided Tour of a Spill (2021), and Life on the CAPS (2022) — are old friends and family members, or artists whose work she admired from afar and later befriended whilst collaborating.

One such mutual admiration-turned-collaboration is the friendship of Bennani and Fatima Al Qadiri, a Los Angeles–based artist and composer (and longtime Bidouni). Al Qadiri’s throbbing score for Life on the CAPS lends the film an at times ominous atmosphere, evoking, in her words, “the darkness of childhood.” Al Qadiri’s music often revolves around cultural translation, mistranslation, and reinterpretation across time and place. Her most recent album is Medieval Femme (2021), a suite of songs inspired by the Arab female poets of the Islamic golden age.

Here, Bennani and Al Qadiri join Negar Azimi and Tiffany Malakooti for a wide-ranging conversation about fangirling and friendship, comparative world-building (in sound and image), cyberpunk memories, the delicate art of not fucking around with “folk music,” and the enduring appeal of lo-fi aesthetics.

A version of this conversation also appears in Meriem Bennani: Life on the CAPS, an extended exploration of Bennani’s trilogy, with essays by Emily LaBarge and Elvia Wilk and conversations with Omar Berrada, Amal Benzekri, and Aziz Bouyabrine. Meriem Bennani: Life on the CAPS is published by Bidoun and The Renaissance Society.

Negar Azimi: If you’re game, we could start in a really straightforward way: when did you two become aware of each other’s practices?

Fatima Al Qadiri: Meriem, you want to go first?

Meriem Bennani: Yeah, I think I probably got to know your music first. I’m trying to remember, but I think it was when you were making music under the name Ayshay.

FAQ: Oh, yeah, yeah.

MB: It feels so long ago, but I was so into it. I remember a CD with this elaborate calligraphy on it… it actually looked like something you would buy at a Qur’anic shop, and then there was this crazy sound —

FAQ: It was 2010. I released the mix Muslim Trance and an EP almost at the same time.

Tiffany Malakooti: It was just after your Bidoun season.

MB: I always tell Tiffany that I have FOMO about early Bidoun. I feel like there was this magical moment that I totally missed. I romanticize it. Probably because I wasn’t there, you know?

FAQ: Your FOMO is in the right place.

NA: Fatima, your Kuwaiti dating memoir and “Children of War” feature with Khalid [Al Gharaballi] remain two of my all-time favorite pieces in the magazine.

MB: Oh, I also remember seeing a photo of the two of you that I found so hot, Tiffany and Fatima. Maybe it was a DIS [magazine] thing?

FAQ: Oh yeah. It was a kind of standalone artwork. It wasn’t me though, it was my childhood friend.

MB: Tiffany, you were kind of butch with a Kuwait hat.

TM: Yeah, I’m like a horny boya1 in a dishdasha.

FAQ: Yeah, you’re a boya. That was a recreation of the album cover for Haifa Wehbe’s “Boos El Wawa.” Haifa is playing a ghanujha, a Levantine word for an infantilized adult woman, a sort of “baby lady.” You know, the kind of person who’s always whining, “My tummy hurts. My head hurts.” [Laughter] I mean, let’s be honest, it’s me. I’m a ghanujha, too.

MB: I just want to say that, to me, all of that was mind-blowing. That photo really stayed with me. I was like, This is gay and very cool and… too many things! I felt like a child, amazed that a world like this could actually exist.

NA: So Meriem, you were conscious of Fatima in this sort of ambient fangirl way.

MB: Definitely.

NA: Fatima, what about you? Do you have a sense of your first encounter with Meriem’s world?

FAQ: The first time she made a mark on me was during the Geneva Biennial of Moving Images. What year was it, Meriem, do you remember?

MB: 2018. That’s when we met.

FAQ: Oh yeah. That’s when we met and when I first saw her work in person. I was floored by the person and the work. It was by far the best in the biennial.

TM: The work was Party on the CAPS, right? The first film in the trilogy?

FAQ: Exactly. I was like, Why did it take me so long to meet this woman? I was so mad, you know? The whole time I was watching it I was like, Please make another film like this and I’ll score it.

MB: You never told me that. That’s so cool.

FAQ: I watched it twice. And I don’t watch anything twice; that’s how much I loved it. I’m like, I did my homework. The way it was installed was so crazy. There were these enormous magnifying glasses! It was insane. You know?

NA: Yeah.

FAQ: I’d never seen any art film installed that way. The whole thing felt so futuristic. Dubai might be the closest thing in spirit to futurism in the Arab world, but watching that made me feel like Morocco was on another tip. She had created this amazing world. Her skills in mythmaking were so powerful. Life on the CAPS was just so, so impressive.

NA: About Meriem’s world-making, did anything about it feel familiar?

FAQ: It felt familiar enough. I mean, the Troopers! I grew up after the invasion, the first Gulf War, and the occupation with its heavy American military presence, so when I saw the Troopers, I immediately related to that.

NA: Yeah, I can see how for a Kuwaiti of a certain generation, the American inflection on the Arab world is something you’re proximate to. How did the collaboration come to be?

MB: The initial idea wasn’t to make this third film narrative at all. I had been watching a lot of daqqa on YouTube and wanted to stage a singular performance inspired by it. I thought it would be a dream to work with Fatima on this. That was really the starting point. Eventually, we talked and exchanged videos, and that’s when Fatima showed me safga, which is so beautiful.

FAQ: It’s the Kuwaiti equivalent of the Moroccan genre. The word just means “clapping” in Khaleeji dialect.

MB: It’s beautiful, slower. So I began to imagine a performance on the CAPS, reimagined in the future and scored by Fatima. But that’s not how it played out. First of all, she wasn’t really into that idea. She was like, I don’t do that.

FAQ: It’s challenging to work with folk music, because nine times out of ten it ends up sounding like World Music Café Latte.

MB: And then I realized that something was missing for me, too. I thought, Wait, I can’t just make one really perfect scene without a story attached. I care too much about the people involved. So that’s how we ended up making a narrative film.

NA: Fatima, did you see a lot of safga in a vernacular context growing up?

FAQ: Yeah, of course. It’s one of the hallmarks of being Kuwaiti, a real Kuwaiti. I don’t feel like anyone teaches you how to do it, you just wake up and you know how to do it. That said, I don’t really know how to do it. [Laughter] But I pretend that I can. My dad can do it really well.

NA: What’s the primary context in which it happens?

FAQ: It’s a celebratory thing, but it’s also just done for fun. It can be very casual or very ceremonial. It could happen in the schoolyard or it could happen at a wedding, wherever. You need two people to do it, but it’s much more fun with a larger group. When it’s two, it’s harder to do. If there are seven or eight people or something, you can kind of catch a rhythm. It starts simple, then can get very, very complicated.

MB: It’s like Fatima said: a thing that you intuitively know how to do. I was watching a lot of YouTube videos of daqqa and safga, and there are these moments where everyone’s so synced, where everyone knows how to be together in this magical way. It’s beautiful.

NA: It sounds utopic.

MB: Yeah. The daqqa tradition takes place in Marrakech, and it can last for hours. It starts very slow and then fades into a superfast rhythm. It’s all about control. In a way it’s the opposite of Moroccan shaabi, which is kind of all over the place. Shaabi is like car racing, you know?

FAQ: This is the thing that I’m always telling Meriem: Moroccan music is so hectic! I really love it because our folk music is slow, like a soft ocean wave. You can tell there’s a lot of hash present. [Laughter]

TM: Or it’s just like a different type of trance.

FAQ: Yeah. The Moroccan stuff is really so up-tempo, you know?

TM: More like an exorcism than a sea song.

FAQ: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Safga can also get very frenzied, but nothing like a Moroccan daqqa. The peak is so insane. It’s like coming up on ecstasy, you know?

MB: It’s very spiritual, actually. It’s like club music.

TM: Yeah. We wouldn’t be the first people to observe the similarity between the ecstatic structure of —

MB: A club and a trance. I want to say something before I forget. Obviously, Fatima, I’ve been a huge fan of all your albums, but what partly inspired me to ask you to work with me was this track in Atlantique of the Senegalese wedding procession. It’s my favorite. I find it so beautiful. I was interested in how you treated that scene as a composer. You overlay your own music so sensitively over the wedding procession. There are so many musicians who take samples, especially folk samples, and produce something cheesy. I wasn’t sure if there could be another possibility, another way of treating such a sample. It’s almost as if you added emotion to the percussive moments, accentuating it but also respecting it. It felt surreal.

FAQ: Negar, you mentioned the radical nature of the clapping. When it comes to imagining a radical trajectory of the folk genre, Meriem definitely achieved that lyrically. Meriem, did you write those lyrics with someone or did you write them yourself?

MB: The song at the end?

FAQ: Yeah.

MB: Aziz wrote them.

FAQ: Oh wow, cool. That’s what I’m saying. Musically it felt very traditional, but where it felt very radical was lyrically. I had never heard lyrics like that with that kind of music, ever.

NA: The lyrics — what struck you about them?

FAQ: They felt revolutionary. Originally I was supposed to write music to that scene —

MB: Yeah.

FAQ: And we both agreed in the end that it wouldn’t work. It was so special to hear it raw, with a cappella and clapping, that anything on top of it would have… I don’t know. It just didn’t make sense, you know?

TM: Was there a risk of fucking it up?

FAQ: Absolutely. A lot of Western producers go around the world and chew up folk music without any relationship to it. I had always been very, very wary of that. I wanted to see how well I could react. It was kind of an experiment. My thinking was, Okay. If this fails, I just won’t work on this soundtrack.

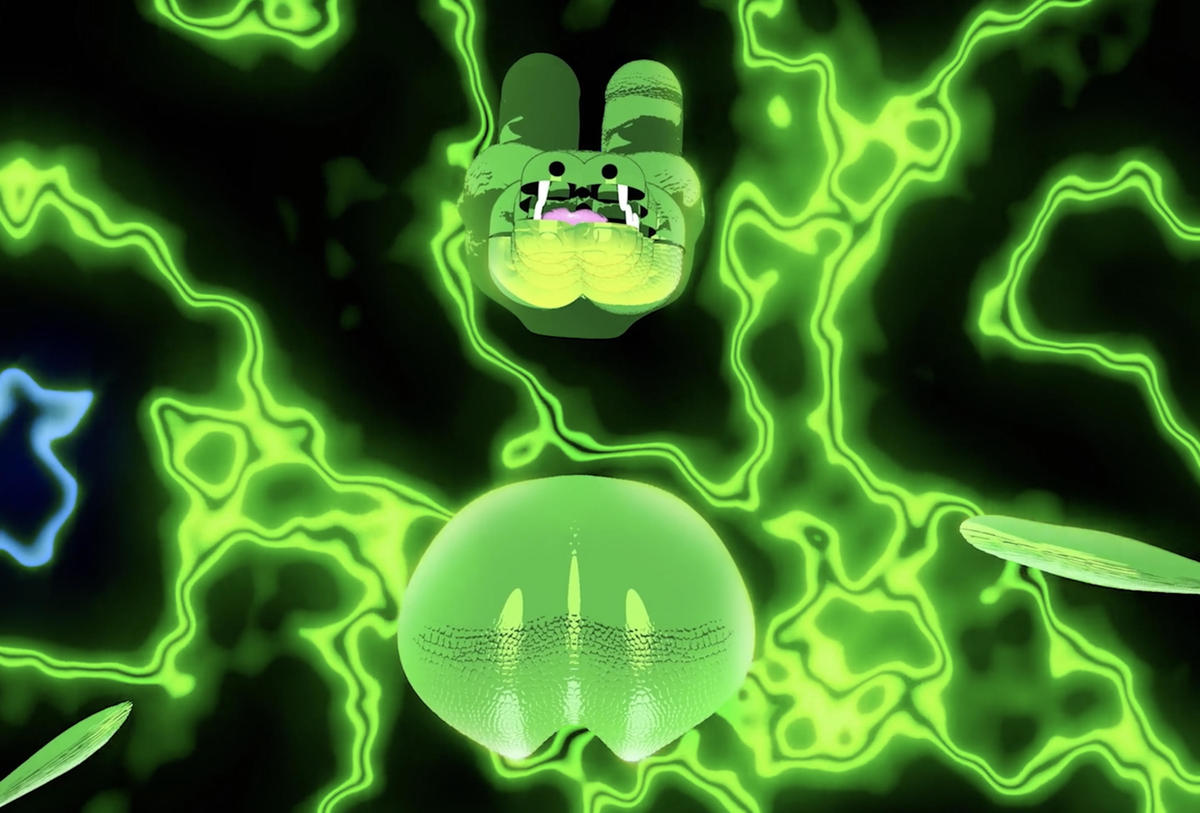

MB: I wanted to say something else about Fatima and me, what connects us. It turns out she watches a lot of anime, and anime has been hugely inspiring for my animated sequences, especially in this episode — the way I played with 3D imaging, the sharp shadows, the glowing. If I’m not mistaken, I also I think we have the same favorite soundtrack, which is for the film Akira.

FAQ: Yes! Watching anime is one of my earliest childhood memories. We used to watch Galaxy 999 on Betamax. It was in Japanese and subtitled in fusha [classical Arabic]. None of us could understand what the hell was going on, but I guess we just watched it for the images; the plot revolved around a steam locomotive traveling through the universe. You know, Kuwait TV had a lot of anime dubbed into Arabic; my sister and I were obsessed. So yeah, I was going to say the vibe for me for this score came from a place of innocence. Whenever I think of armies and this awful territorial situation and revolution, I’m instinctively taken back to being a nine-year-old. And as I relisten, rewatch the film today, I realize it’s very innocent-sounding, with the exception maybe of the daqqa moments. But overall, it’s very childlike.

TM: That’s funny. Because I assumed that you might talk about how this episode is the dark one.

FAQ: The childlike aspect represents the loss of innocence. It’s the darkness of childhood. When it came to the choice of instruments, I wanted to produce these very simple synth sounds that are neither here nor there. I wanted it to sound a little bit like electronic music from the middle of the ocean, if that makes sense. I feel it’s really easy — for me anyway — to identify specific synth sounds with an era, a genre, and I wanted this to sound a specific way that wasn’t attached to a place. There’s something about the story — take the character Bouchra and the Trooper she was seeing, the dog Sweetie, plastic-face syndrome, etcetera — that made me feel like I was reading a new kind of Neuromancer, you know? There’s something about all of this that takes me back to being a kid and that sense of childlike wonderment. That’s how I responded to her world.

NA: It strikes me that both of you are revisiting vernacular traditions in irreverent but also somehow sensitive ways. Both of you also grew up in multilingual, multicultural contexts in the Arab world and could have easily turned away from these traditions, if that makes sense. So how did you get here? Fatima, as an honorary chicken nugget, perhaps you can start?

TM: Maybe you should explain what a “chicken nugget” is.

NA: I guess we first learned the term from Fatima years ago, and it signifies a person who’s most fluent in a colonial language. Is that a fair characterization?

FAQ: Yeah, I mean, it’s a derogatory term! I don’t go out and announce that I identify as a chicken nugget, but unfortunately there’s a level of Arabic mastery, especially classical Arabic mastery, that I don’t possess, and that automatically makes me a chicken nugget.

TM: Meriem, I remember you telling me that the Moroccan equivalent of a chicken nugget was a Petit Danone?

FAQ: What’s the word in French?

TM: Danone. Like the French yogurt brand.

FAQ: Oh my God.

MB: It’s actually more precise — it’s like wald Danone or bint Danone, son or daughter of Danone. [Laughter]

TM: That’s so good.

MB: Anyway, I’m totally a bint Danone. My biggest fear is being interviewed by a Moroccan in Darija.2

FAQ: Yeah, I’m sure, babe. I’m sure.

NA: Meriem, how does this condition inflect your life? Beyond that fear, I mean?

TM: She made a whole work for the Whitney Biennial about it!

NA: That’s right. Mission Teens: French School in Morocco.

MB: Well, it came out concretely during the shoot, when I had to explain the concept of the CAPS to everyone present. I was so shy, I have so much shame around my Darija that I had to lean on Aziz the singer to help direct. That’s actually how he became the main character; I needed an ally. But about turning inward toward vernacular Moroccan stuff, there’s definitely an introspective element of trying to understand my education and my biases and how my brain was taught to think and trying to undo that. But at the same time, as you guys know, for me everything is pretty intuitive. I gravitate toward things I genuinely love. My love for daqqa is not just about being political; I genuinely love it. Being excited about something is the only way I can start thinking about it. I need to be moved in some way, you know?

NA: Totally.

TM: Did you listen to Arabic music when you were younger?

MB: I guess I didn’t really listen to Arab or Moroccan music. I was very much rejecting it. And I was shy to dance, too. At parties I was always like, I can’t dance! As a teenager I was a skater and a surfer, so I was listening to Offspring and Green Day and Nirvana. I didn’t pay attention to the shaabi music in the streets, blasting from taxis. And now it’s my favorite music. Maybe mine is a classic story.

NA: You mean you had to leave, go to New York, to get into Moroccan music. Is that right?

MB: Exactly. I think my way into Moroccan music was listening to a lot of West African music to start, and this was like fifteen years ago or so in America. Then I started to listen to all kinds of things from Africa until I gravitated back to Morocco. That was a revelation. I found it so different from my youthful associations.

FAQ: I was going to say that while watching Party on the CAPS, I instinctively knew that Meriem had really good taste in music. That’s also one of the reasons why I wanted to work with her. You can always tell a director’s relationship to music by the musical choices in their films. I could see that she was a music nerd. And then there’s her YouTube stuff…

MB: When I told Fatima about my YouTube page, she was like, You have to remove it immediately.

FAQ: Yeah. I was, like, Girl, get that shit off the internet.

NA: Why?

FAQ: Because I didn’t want white boys to cannibalize it. I was like, Eventually Diplo will find out about it, and he’ll just rape the whole page. Oh my God — you could not quote me on that last one. But you know what I’m saying? I rarely ever share. The only stuff that I’ve really shared was occasionally on Global Wav, my column in DIS. And it was always very tongue-in-cheek, funny videos that were more about aesthetics and style rather than actual good music.

TM: Meriem, can you talk about the parties that your mom hosts, like the one featured in Party on the CAPS? From where I’m standing, it looks they’re women-only and you hire a particular type of musician to come to the house to perform. Did you grow up with those gatherings?

MB: Yeah. In a way it’s very similar to us being at my house in Brooklyn and you playing music on the phone. They’re just gatherings. And it’s not women only, but it’s often an afternoon thing, and because fewer women have day jobs, there tend to be women present. So it’s gendered in this way, but there could be men, too. It’s often very casual, like my mom and her cousins playing at home, clapping and singing and having fun, but it could also be more formal; there could be a le3aba, a kind of hype person, like an entertainer who comes with her own dancers. She’s the woman who rolls around on the ground in the first film. Or sometimes there’s a band that comes and sings. Or there could even be someone who sings traditional folk songs with a group of women who play percussion. In other words, there’s not just one kind of party. But there’s always an intimacy and a freestyle relationship to lyrics that I love. And if it’s only women and everyone’s comfortable, the lyrics can get really, really dirty.

NA: Fatima, when you first watched Party on the CAPS, in Geneva, how did that party scene feel to you?

FAQ: It felt like old Kuwait — Kuwait before the money, when there were fewer nouveau riche values and societal norms were looser. If you listen to older folk music, the very earliest recordings of Kuwaiti radio, the lyrics can get X-rated, and then as we move into the modern age or postmodern age, censorship rises and the lyrics of the old songs are adjusted to reflect a new conservatism. And it’s sad, but that’s what I felt watching Meriem’s film: I was like, Wow, this feels like Kuwait in the 1950s. That vibe, that lack of restraint among people, just partying and having fun and doing drugs and just really being in the zone — that used to happen. Opium was sold. Hashish, too, used to be sold in the vegetable market. It probably stopped in, I want to say the early 1960s, if not in the late 1950s. My mom remembers going to Mubarakiya, the main old market in Kuwait, the oldest souk, and seeing it sold with the vegetables.

TM: I guess hash is a vegetable.

FAQ: Yeah, it’s a fucking vegetable.

NA: How about we return to this idea of music as a sort of temporary autonomous zone, to invoke the late Hakim Bey — may he rest in peace — a place where people might be different, be crazy, raise questions they can’t otherwise? Tiff and I have been talking about Egyptian shaabi, or mehraganat, which kind of peaked during the Egyptian revolution. It’s been mainstreamed and co-opted since then, but —

FAQ: It’s funny that you should bring up mehraganat. I think that when it comes to the radicality of music production, what has definitely changed a lot in my lifetime is the technology. Before, in order to be a musician, you were either playing an acoustic instrument or you had to have access to a music studio, which was extremely expensive. And then, for my generation, you might start out with these tiny keyboards, like I did, and then graduate to a laptop. Now you can make music on your phone if you want to. I feel like musical genres become less radical as they become more polished. Like you said, this is what happened to mehraganat: it became something made in professional studios with professional engineers, and it sounded shinier and moved further and further away from its roots. For me, some of the most exciting music being made is the worst-quality music, the worst-quality MP3 — it’s almost a disintegrating MP3. I tried to include some of that sound quality in the Atlantique soundtrack. I didn’t want it to sound shiny, and this is also why I kept Meriem’s soundtrack relatively simple, melodically speaking, but also in terms of sound quality. I wanted it to sound more real, let’s say. As you move further away from that realness, things sound more and more like a Hollywood film, and that’s when you become… You lose your soul, I think, as a composer. As a musician, I always have to keep some element of my production and process as an artist as lo-fi as possible.

MB: Fatima, it’s funny because I sent you those samples of daqqa that had been ripped from YouTube videos and you played with them. And then one night during the shoot I booked a music studio for you where we recorded all these claps and samples and I guess those didn’t make it in. And that was kind of cool, too, no? What you ended up using, the rough stuff, had the energy of a real ceremony.

TM: Fatima has a touch for the low bit rate. [Laughter]

FAQ: I really want to write a book called The Disintegrating MP3.

MB: I identify with what Fatima says about lo-fi. For example, if I have access to a bigger budget, I don’t think that necessarily means I should have higher production values. Party on the CAPS was the first time I ever had a budget to make a video, and I was like, Oh, I’m not going to hire DPs. I’m just going to throw a massive party at my grandma’s house! [Laughter]

NA: Meriem, I’ve heard you think aloud about how rai and shaabi music have been resistant to mainstreaming in part because they absorb technology but aren’t domesticated by it, if that makes sense.

MB: Yes. Shaabi in particular is so hardcore, it’s hard to —

NA: Tame.

MB: Exactly. I mean, the level of Auto-Tune alone is insane. And so these small shaabi labels carry on all around North Africa, which is very beautiful. In a way, it’s an inspiration for the way culture works on the CAPS.

NA: How so?

MB: It’s a vision of culture that is malleable, that is easy to make, but also firmly its own thing.

TM: That sounds radical.

NA: And a fine place to end.

1. A boya refers to a lesbian or masculine woman in Kuwaiti vernacular Arabic.