Courtesy of the artist

Beirut

Closer

Beirut Art Center

January 15–April 2, 2009

More than a thousand people attended the opening of the Beirut Art Center, many of whom described the event as “magic.” The project took nearly five years to realize; initiators Sandra Dagher and Lamia Joreige dodged one political crisis after another while searching for a space, raising funds, and creating a framework for public programming.

If the art center represents a major piece of what had been missing from the cultural scene in Beirut, then its inauguration also marks the symbolic end of an era. For the last fifteen years, Beirut’s contemporary art scene has been constantly on the move. It has appropriated the elements of an alternative infrastructure and assembled a strong semblance of a community along the way, but it has always been peripatetic and not entirely institutionalized. This aspect of the Beirut art scene has been, to some extent, romanticized. It is now, for the most part, over.

The Beirut Art Center’s inaugural exhibition, titled ‘Closer,’ addressed notions of privacy and intimacy, considering the point at which personal narratives become material for public expression as artworks. Considered in a wider context, the possible meanings evoked by the title of the show could also be read in relation to the lack of public spaces, spheres, and institutions in Lebanon, and in light of how the boundaries between public and private are constantly redefined by cultural initiatives such as the Home Works Forum organized by Ashkal Alwan.

These and other ideas about audience, infrastructure, urbanism, and the state lay just beneath the surface of the exhibition. They were never explicitly articulated, though, as the primary concern of ‘Closer’ was artistic practice itself. The show included the work of eleven artists, working in video and photography as well as text- and web-based media, who all directly or indirectly staged some aspect of themselves in their work. The eclectic choice of artists — from the Lebanese composer and sound artist Cynthia Zaven, who was showing her work in Beirut for the first time; to Akram Zaatari, Tony Chakar, and Lina Saneh, who have been ubiquitous in the local art scene for a decade or more; to Anri Sala and Antoine D’Agata, who have rarely, if ever, shown their art in the region — raised questions, created curious correspondences, and gave rise to multilayered readings of works that were already, in some cases, quite familiar (Chakar’s 4 Cotton Underwear for Tony; Zaatari’s Saida. June 6, 1982).

But still, one could ask of the title, Closer how, closer to what, closer to whom? How close, for example, was Lisa Steele’s twelve-minute black and white video from 1974, Birthday Suit, with Scars and Defects, to Lina Saneh’s 2007–2008 web-based project Body pArts? Both works drew on the history of body and performance art. Yet the technologies employed distanced them substantially, as did the works’ political undercurrents.

In Birthday Suit, Steele set up a stationary camera in a room, took off her clothes, and proceeded to approach and retreat, offering a closeup of a body part with each pass and showing, for example, the mark on her finger, nearly severed at age five; the permanently discolored nail on a toe stubbed while running barefoot at age six; and the scar below her left breast, from the removal of a benign tumor when she was twenty-six. The artist’s methodical presentation and the flatness of her narrative voice were at odds with the tender manner in which she touched each scar and defect with her fingertips, as if summoning the memory of being either physically or emotionally hurt. Here, the camera acted as an agent.

Lina Saneh’s mediation was more contractual. For Body pArts, she attempted to circumvent Lebanon’s religious laws, all of which prohibit cremation, by creating a website through which fellow artists might “sign” different parts of her body, a transaction that effectively turned them into artworks (“the signing of the artist’s share of the total fee paid for the work will constitute 65 percent”), in return for their promise to incinerate the “parts” in the event of Saneh’s death, thus achieving cremation through the mechanisms of the art market and the internet. Saneh countered the objectification and commoditization of the body with what resembled an emancipating gesture; she fought one system (religious laws) with another (the art market), but at the point where those two met were the engaged and often emotional statements of her fellow artists, whose interventions gave the piece its power.

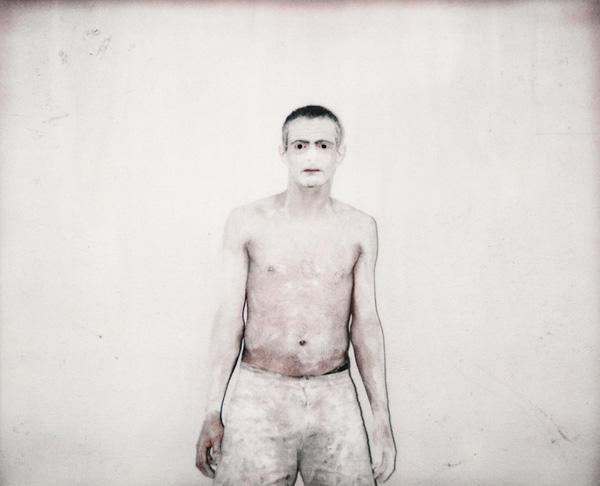

Courtesy of Magnum Photos

In work after work, ‘Closer’ posited the individual, the voice, the story, the anecdote, against the grand sweep of history and its accounting of political, geographical, and even spatial realities. Antoine D’Agata’s grainy self-portraits were taken in brothels from the Canary Islands to Gaza. The images captured the artist’s disintegrating, ghostly body, caught in the midst of an action that nearly reduced his form to abstraction. The squares of the room and the bed (and in them, the blur of a brief lover) created the frames through which D’Agata penetrated different geographies. The camera alluded to stories without really telling them. The location of each image, in parentheses next to the photographs, suggested adventures without ever disclosing them.

The works in ‘Closer,’ then, might have played with privacy, but the “I” in the pieces shown — the personal, the intimate, the interior — was always staged and always performed. There seemed to be an inherent and possibly productive contradiction in the fact that the Beirut Art Center had chosen the theme of privacy for the opening of a public space. It was an awkward encounter, a first date, a relationship between the space and the public that ended, as the best first dates do, by getting a little closer.