Julien and Gabi Asfour were born and raised in east Beirut, and grew up amid Lebanon’s several civil wars.

Bidoun: Do you remember the beginning of the war?

Julien Asfour: I don’t think anybody was aware of when the war started. It just kind of crept up. Every day you’d think, “Oh, it’ll be done by tomorrow. It’ll be over, things are under control.” Nobody would tell us what was going on. I guess the parents were taking all the responsibility for themselves. So we didn’t really feel it, somehow. We still had to go to school, except during bombardments. The best days were when the bombs started coming down, because you didn’t have to go.

Gabi Asfour: It’s a fun day for the kids. When you start hearing the bombs in the morning, it was like “Yeah! No school today!” Sometimes the bombing would be for a day, sometimes it lasted a week, sometimes a month. If it was more than a week, we would pack up the car and go up to the mountains and ski.

JA: But it got worse. It kept getting worse and worse, every year.

GA: It just kept escalating. Every year at Christmas, everybody went to church and prayed for the end of the war.

We lived on the east side of Beirut, the Christian side. The interesting thing was that we are Christian Palestinian, and the first war that started was between Muslims and Palestinians. Later on it became a war between Muslims and Christians. So even though we were Christians in the Christian part of town, we still felt like outsiders. It was very confusing. We couldn’t speak Palestinian Arabic; we had to use Lebanese slang all the time. Once, after things escalated, the people who run the grocery store freaked out and started screaming “You assholes! Palestinians! You traitors!”

But mostly we were fine. We were kind of like, cool, so the kids around us were smarter, more intellectual people. They looked at our being Palestinian as a funny thing. They always made fun of us, behind closed doors, but never in public. There were a lot of crazy people out on the street.

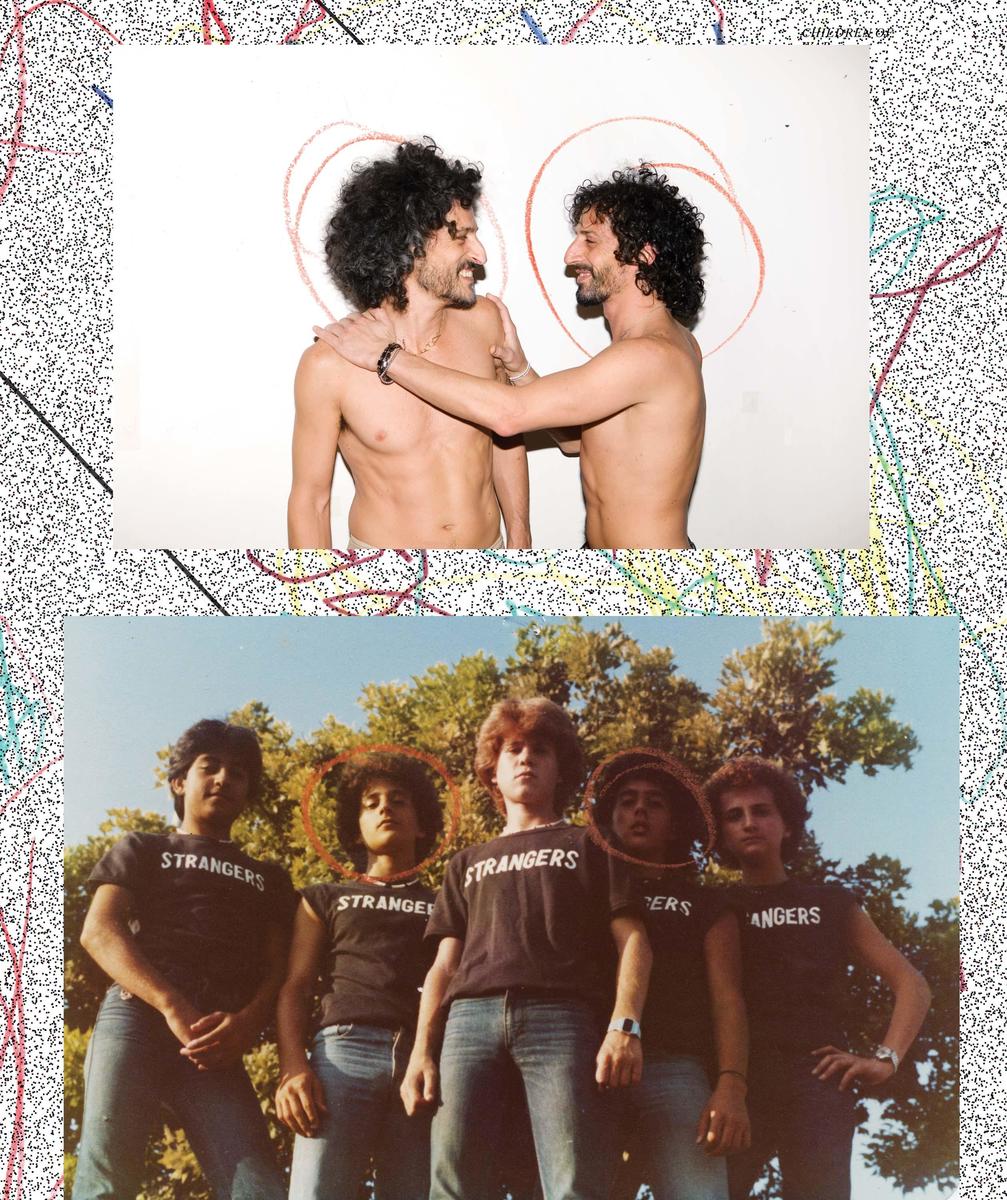

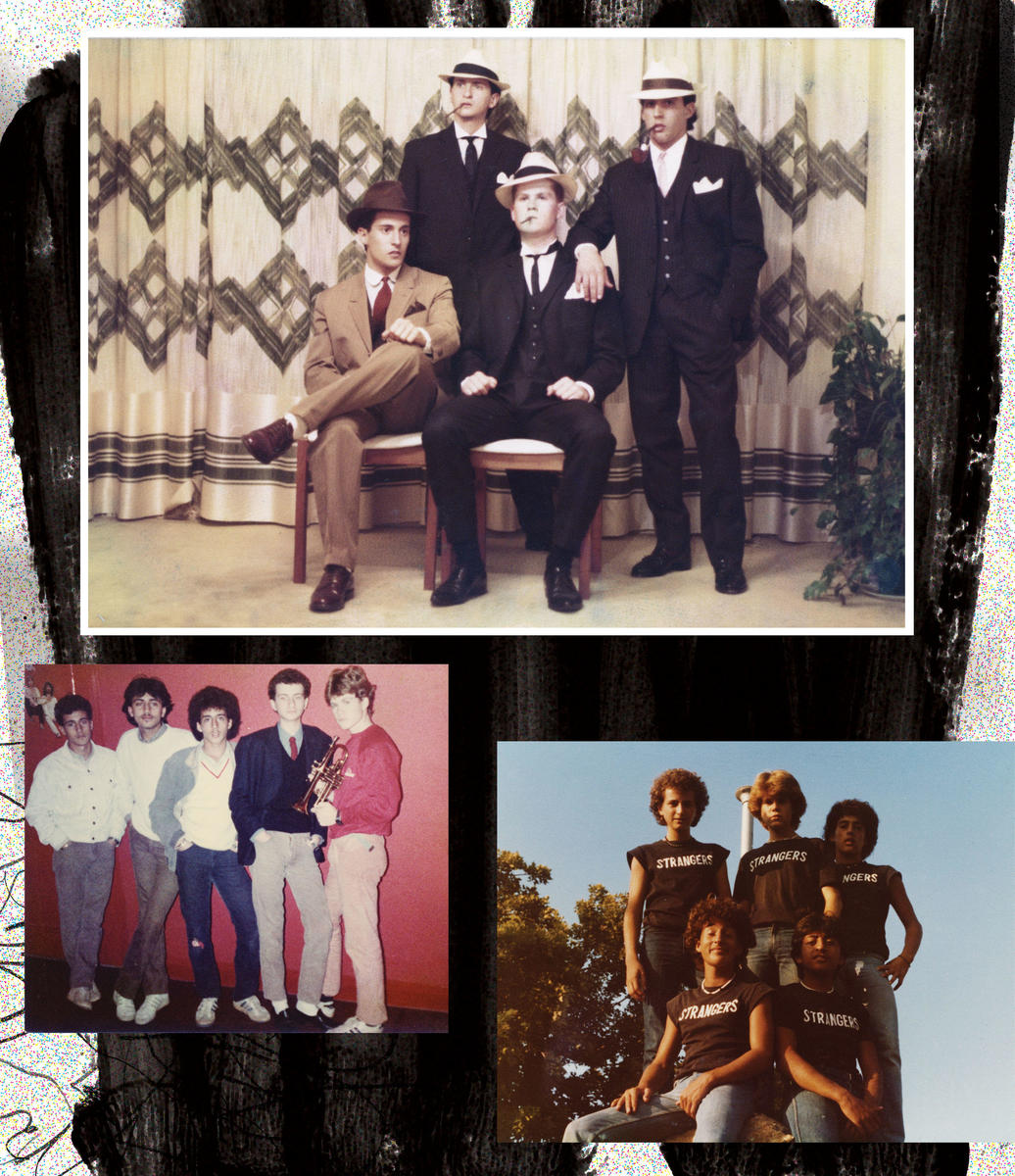

JA: You know, we spent a lot of time on the street. We had a crew that did a lot of graffiti. The name of our gang was Strangers, but with dollar signs. $TRANGER$. And we were five kids who actually were strangers. We had a British guy, Bobsy, and a Colombian guy, Felipé. And then there was Congo, who was just incredibly hairy.

GA: Hair everywhere.

JA: That’s why we called him Congo. Well, that, and because his dad owned a plant that turned animal skin into leather. And he had a pickup truck, which we would use sometimes, and it stank like hell from all the fresh skins in the back. So that was why we called him Congo — that truck reminded us of Africa and safaris, and him being hairy like a monkey.

We were like a family, a bunch of kids huddled together. Though Felipé was kind of a wimp. As soon as he heard gunshots, he would run up the stairs. We’d be playing soccer, and then there’d be Felipé, watching from the balcony. He didn’t go out with us as much, because his parents were very strict. Our parents were strict, too, but we kind of molded them.

GA: We had certain whistles that we would use to signal that we were there, or to get someone to come out. And we had our own dialect — we would reverse the words so that nobody would understand what we were saying, not even our parents.

JA: We had the whole deal, you know. We were doing graffiti at the same time New York was doing it, at the start of the eighties. You’ve seen the movie The Warriors? That definitely had an impact on our behavior. We would walk around with black T-shirts with white writing. $TRANGER$. Nobody in the Middle East did graffiti, ever. It was inconceivable — what is this craziness? Everybody wanted our —

GA: — everybody wanted to be a part of it. But they couldn’t break in. We were very tight.

JA: There were parties every weekend, girls from our school, girls from the neighborhood, girls from the next neighborhood. Everybody wanted to have us at their party. We would always dress the same. Sometimes we wore the T-shirts, sometimes we would wear my uncle’s old suits — kind of like The Untouchables, with the hats and everything. At one point we had these space suits, white overalls, like in car racing, that were flame-repellant, and we would wear them around town to parties.

GA: We had so much freedom. Sometimes I feel sorry for any kids I might have one day, as there is no way they will have the kind of experience we had in Lebanon. I mean, growing up as a teenager with no police around, no traffic laws, no one to check your driver’s license or stop you from going down the one-way street the wrong way —

JA: — there were no one-way streets —

GA: — or from stealing your parents’ car or going off to see a girl or have a drink at the bar. As teenagers we did everything.

Bidoun: Was there anything you did then that you look back on now and say, How the hell were we allowed to get away with that?

JA: Well, we had all kinds of games with guns. Not real guns — BB guns — but still. We used to shoot at people from the seventh floor of my friend’s house. We spent hours and hours on the balcony, shooting. We were so good! We also used to hide in the bushes at night and throw glass bottles at cars that were driving by on the road at the bottom of the hill near our house. When I think about it now, I am furious at myself, you know. But at the time it was a game, and when you heard the bottle hit the car, it was — instant celebration.

Here in New York, you know, you see kids hanging out in the streets, maybe they’re drinking, you know, 40’s in a bag, always looking out for the police. You feel like you’re in prison. In Beirut there was no sense of fear. You never had to watch your back. You just had to keep your ears open for bombs or gunshots that might come your way.

A lot of the time it was quiet. On days when there wasn’t any fighting, you would just hang out, drink beer in the street, drive the car — you don’t need a license, there’s no police, no traffic lights, no lanes, no speed limit. No drinking age. And on top of all this, Lebanon is such a small country. Everything was so accessible. Depending on the season, you would go skiing or go to the beach or go to the river for a picnic. You had everything.

Bidoun: Were there other gangs?

JA: Yeah, there were. And we got into street fights. They hated us.

GA: There weren’t gangs…

JA: Remember the street fights?

GA: I mean, they weren’t a gang. But we did get involved in one street fight. A big one. Like, twenty-five people against twenty-five people. But it started out twenty-five against five. Against the Strangers. We were surrounded by all these bad-ass motherfuckers. And we were like, fuck, we’re fucked. But we were in our neighborhood, and in our neighborhood there were some really bad-ass motherfuckers.

JA: Who know us. Lucky for us, you know.

GA: Christian militia types. It’s funny. One moment, we were scared shitless. I was shitting my pants. But the moment that we had these real fighters show up — these guys killed like five people a day — and they were with us, and all of a sudden —

JA: You don’t know when the fighting begins —

GA: — Julien is, like, punching and kicking somebody on the ground, and I find myself with somebody’s head in my hands, banging it on the sidewalk, blood gushing all over the place.

JA: That guy ended up in the hospital.

GA: That’s what happens, I guess, when you have somebody backing you up. And if it had gone the other way, it would have been us with our heads being banged against the sidewalk. The war really taints your perceptions toward life. You appreciate life much more, because you’re so susceptible to death. You are like any other person who was at that moment dying right around the corner. A bomb could drop on your head at any second, or you could be kidnapped, or shot by mistake, or have a stray bullet in your head.

JA: You could be sitting in your house and a bomb could just go through the house. There was no place that was safe, except down in the shelter. One time we were at home and I was with my dad making a salad, and a bomb exploded really close to our building. I was standing there with my dad at the salad bowl, and the shrapnel from the bomb went right through it.

Not to mention the car bombs — there were so many car bombs that would just wipe out half of a building. Sometimes you would see remnants and blood on another building. But for us, it was fun. It was like watching a movie of war, but we actually lived it.

Bidoun: You got shot, right?

JA: Yeah. It was just a typical afternoon. My mom was making lunch and a bunch of kids were hanging out in the street playing soccer, and at one point we started hearing all these bullets. We didn’t know where they were coming from. The next thing I know, someone is telling me that my arm is bleeding and I look down — and I started to feel that it was heavy, and I realized there was a bullet in my arm. A sniper had caught us at just that moment. Of course, it was the talk of the neighborhood. I didn’t want to tell my mom, so she wouldn’t freak out. One of my friends took me to the hospital, and I got the bullet removed and my arm stitched up. And of course my mom found out, and she was freaked out and she came to the hospital. It was nothing in the end, the bullet went straight through the muscle between the bones, no arteries, no blood vessels, no nerves. It was supercool. The funny thing is, throughout the war, I had always wanted to get shot in the arm, I wanted to get a bullet in the arm, and then it happened.

Bidoun: Wait, what?

JA: I don’t know… it had something to do with Rambo and Rocky, you know, getting shot and stitching himself back up, some sort of superhero thing.

GA: It’s more about making friends with death, and being really okay with it as something that is natural. It actually gave us joy, you know. My favorite thing was to wake up every morning and go look for the dead body. If it wasn’t around the corner, we would get the binoculars and go up on the roof. But I wanted to see it: where the bullet went inside the person, whether the stomach was on the floor, whether his face was all crooked. Whether his shoe was off or his pants were down, how his hair looked.

JA: Or somebody would tell you all this, the details.

GA: Everybody talked about the dead body.

JA: The one that sticks in my mind, is — a girl, actually, with a — with a big stick in her pussy. The dead body on the street. That one we actually drove to go see.

GA: I didn’t go with you.

JA: We had heard that at the bottom of a hill at the border of our neighborhood, there was a body of a woman, so we went down to check it out. You couldn’t help but wonder about what happened. When you saw a dead body you always wondered what the last moment of the person’s life was like. There wasn’t anything sexual about it.

GA: But it was exciting. That’s the number-one thing. You forget that you get excited to see gore. As a kid, you’re not really thinking about morals and stuff, you’re thinking about what’s exciting. It’s like video games.

JA: Yeah, it is like video games as a kid.

GA: My most exciting experience was two militia guys who came up to my friend and me. We were, like, nine years old, and they were carrying this guy who was blindfolded — his legs were almost off the floor — and they kind of planted him next to us. They both had M-16s. They put both of them, the machine guns, inside his stomach. And they waited for us to look. They planned the whole thing. So the guy — they did it on purpose so that his guts would come out of his stomach and fall on the grass. And my friend and I were, like, looking at these two guys, and we were like, Fuck you. It was so… immoral. If you’re doing this because the other one killed your brother, fine. But if you’re doing this just to amuse yourselves, and fuck around with some kid’s mind… I was like, Fuck you guys, fuck all of this, I’m not going to put up with this. I’m not going to get affected by it. I’m not going to be scared. I’m actually going to enjoy it. I’m going to remember these guts being spilled, and I’m going to remember you stupid idiots, the two of you representing so many more stupid idiots in the world who’re doing exactly the same thing. So maybe I can say, Thank you for doing this, instead of, Oh my god, they damaged my brain. It’s like the stick in the pussy. That’s how I look at it. So much of the war is this kind of power trip. So much of every war.

I remember there was one guy who was tied to a car by the leg. It was the middle of the afternoon, right there in the middle of the street, and he was bouncing around behind the car, leg dangling. It was like a cowboy movie. The car is moving, the guy’s body is bouncing up and down, he’s screaming, blood gushing everywhere. And these guys are laughing their ass off. And it’s kind of — that’s when you realize, war is not fun. Guys like this should know what kind of thing they are doing. They should realize what it is that they are doing. It kind of comes down to the human soul, the preciousness of the human soul — this is the bottom line. You’re not really just doing this because you want to get your ego fired up. It’s, like, so retarded compared to the preciousness of somebody’s soul. I mean, this is my moral of the war. Besides having fun and all of this.

I got really scared one day. We were in the mountains, and we sprayed the bus that belonged to the head of the militia.

JA: We used to spend two weeks in the mountains, in the forest, every summer. Just the Strangers. Our parents would just leave us. They gave us money for two weeks, and we managed. We had our little tape players and we would listen to Pink Floyd. That was the thing that really developed our music sense, being in the woods with the animals and just listening to Pink Floyd before you fell asleep. Anyway, we had spray-painted the bus during our stay in the mountains, and then afterward we went to the beach. The funny thing is, we were hitchhiking back from the beach, and one of the militia guys picked us up. We thought he was giving us a ride back to town, and then he started driving back up the mountain. We were somewhat kidnapped.

GA: They arrested us. Next thing I know, Julien has a gun inside his mouth and this militia guy is freaking out because my brother’s eyes are always wet, you know, naturally. And this guy is going on like, You were smoking hashish. You know you’re a junkie. This guy was close to losing it. He did not give a shit. There were other guys with machine guns pointing at my head. They wanted to shoot us.

JA: I kind of knew they weren’t going to shoot us. I think they were just trying to scare us to get us to clean up the bus we’d spray-painted.

GA: Yeah, but they would have shot us, Julien. If we had said the wrong words, they would have. Anyway… We got out of it, obviously, but I was like, Fuck the graffiti, fuck the gang shit. We’re gonna end up dead. Next thing you know, we were at a New Year’s Eve party, and there were more guns at my head, another gun in Julien’s mouth. And I’m like, what the hell? I really don’t need this.

Bidoun: Did you have to do army training or anything?

JA: Yeah. It was during the school year, actually. They would pick a long weekend, twice a year, and no one had any choice in the matter. But we were still bad boys in the training camps. You would have to go to sleep at a certain time, lights out, and so we kept the lights on and kept talking. They would try to punish us — they took us out to this pond that was full of frogs and algae and dirty water, and they made us swim in it. And it was more fun for us than the training, of course. We would get punished all the time. The main thing I remember is actually the end of the camp. You would have to line up in a row, and they announced that the troop that stood the straightest, without moving, would be the first allowed to leave. But it was hot, unbearably hot, and people were fainting, and we were like, Fuck this shit. We didn’t care. So we sat down. Let them all go, we’ll be the last to leave. And they got so pissed at us that they actually made us leave! They couldn’t stand us. They didn’t like us, anyway, because we went to the French lycée, and everyone at the French school was regarded as pussies. We didn’t care, we weren’t scared, and it worked. The intellectual pussies!

Bidoun: When did you end up leaving the country?

GA: We left in 1986. We had to leave — things had escalated again. We left on a boat, from the harbor, with maybe fifty people saying goodbye. And we had thirteen suitcases for the six of us. It was a real exodus, like immigrants getting on a boat. And next thing we know, we are landing in JFK. It was kind of strange. When you land at JFK, and you arrive, you’re like, fuck, this is what the city looks like? All these fucked-up bridges, every structure has no plan, and there are black people in the airport, and whoever is running things is, like, Mexican and stuff. We were like, What is going on? What is this country I am arriving to? Beirut is more glamorous, really.

The brothers Asfour live in New York City. Julien is a dentist and deejay. Gabi is a founding member of the fashion collective threeASFOUR.