Chicago

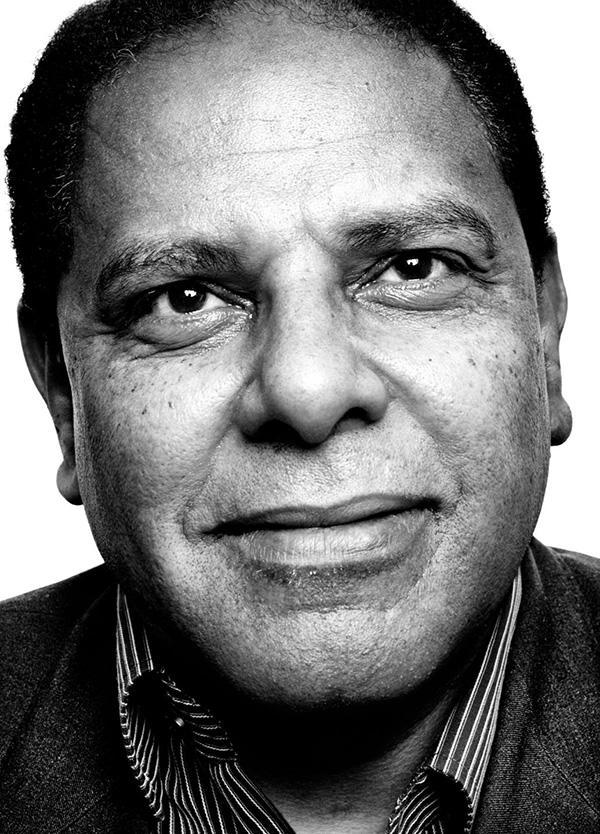

By Alaa Al Aswany

Dar El Shorouk, 2007

Arabic

Patriotism is narcissistic; so are soap operas. Both hang on the sad assumption of a collective viewpoint. Both work by means of stasis, language reduced to slogans or platitudes, meaning to a wafer-thin morality or norm.

Which is why when Alaa Al Aswani introduced soap opera into the Arabic novel — a largely pedagogic genre, in the minds of his writerly generation (of the 1970s) — it was sold and resold and made into a big-budget film. So far, so delightful. At least he’s still writing books; his compatriot and contemporary, Osama Anwar Okasha has abandoned publication altogether to write musalsalat [serialized dramas], wangling all that he and his comrades coveted during the student movement: money, fame, intellectual kudos, and, perhaps most important, access to the minds of the masses.

Aswani’s The Yacoubian Building was less about the triumph of mediocrity than that of the lowest common denominator. What’s distressing is the incredible inanity of that. ”Medium-brow,” is how Aswani’s English translator describes the book. Striving for popularity, Yacoubian resolves into a tile game of colors: yellow for the tabloid, the scandal-mongering, the off-color (read, X-rated); blue for mood; green for (secularized) religious affiliation; red and black for a pumped up sense of national identity.

In Chicago, his follow-up novel, Aswani transports his cast of (stereo)types from downtown Cairo to the Histology Department of Illinois State University — where, earning PhDs, they play out the same sort-of-protestant parable about what it means to be Egyptian today, how one should, as opposed to how one shouldn’t, be Egyptian. It’s a slightly less “colorful” cast, the story’s power deriving not so much from unmitigated urban vice as from displacement, its secrets less revealing of the limitations and prejudices of the omniscient narrator.

More catholically, there’s a conversation about vibrators, a range of risqué masturbation-prayer configurations, a conflict between renegade and true-to-themselves Egyptian doctors, and sundry additions to the annals of “Egyptians (read, self-hating uncivilized country bumpkins) in America.” It’s realistic, but only insofar as it remains simplistic and reductive; in life, the reality of any one individual — and I can vouch for there being many Egyptian individuals who define themselves differently than Aswani does — lies outside the scope of the aforementioned omniscience. This is a literary issue already raised, and variously resolved, many decades before Aswani was born.

Judging by the standards of the popular novel, Chicago is better written than The Yacoubian Building. This is thanks in large part to Aswani having brushed up his technique, which can be read as a stab at something somewhat more high-brow (in line with its superior setting?).

The book opens with a monograph on the history of Chicago, explaining that the etymology of the word, in the local Native American tongue, derives from its being the site of extensive onion farming: a pungent smell. Aswani, a dentist by trade, also provides complex glosses on histology, on the way medical departments in universities work, and on various locales back in Egypt. As the novel progresses, the all-too-Egyptian melodrama acquires clash-of-civilizations dimensions, and any individual traits the characters might have shown, however fleetingly, dissolve into the fray. By the last page I was left with a sense of having been duly distracted, but having learned nothing and experienced little in the way of human engagement. It felt as if I had just completed an episode of the Ramadan soap opera my middle-class family has been praising.

The worldwide rumpus over Aswani is thrilling in that it’s been unparalleled in Arabic literature since Naguib Mahfouz won the Nobel Prize in 1988. Yet the proof is demonstrably not in the pudding; that the reading is easy is the most that can be said of it. Neither the intellectual engagement of Sonallah Ibrahim nor the stylistic exquisiteness of Ibrahim Aslan can be found here. And that is what is distressing. Like patriotism, like soap opera, Aswani is annoyingly mundane.