Tehran

Khosrow Hassanzadeh

Silk Road Gallery

February 8–23, 2005

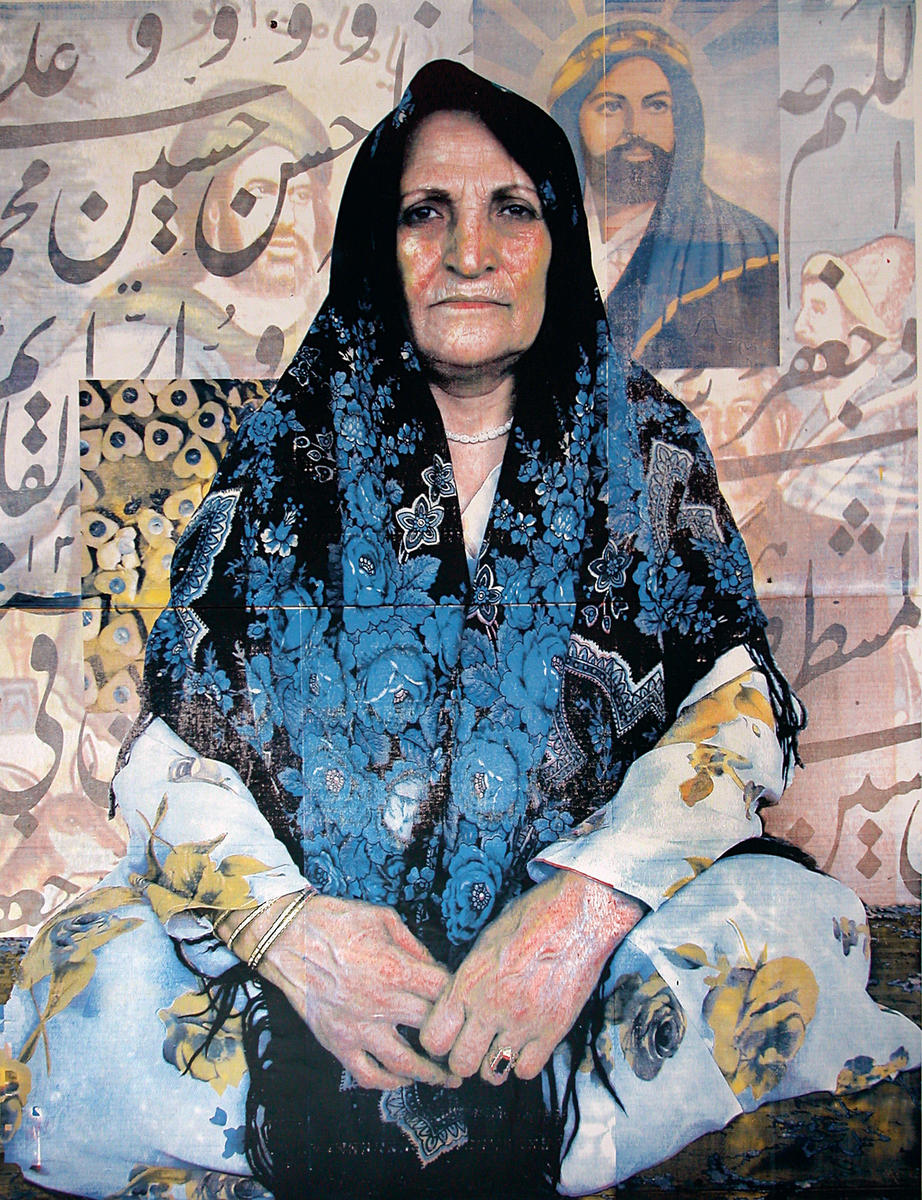

The women sit on the floor like trees rooted in the ground. A Qur’an and prayer mat lie in front of the artist’s sister, covered in a multicolored flower shroud, prayer beads in hand. Another of the artist’s sisters sits stoically with two fingers of her right hand sheathed in her left fist. Unlike his sisters, the artist depicts his mother with a hint of movement; her body graciously sways to one side. Each woman appears against a backdrop of Qur’anic calligraphy, photos of a pilgrim at a shrine, and religious banners. The iconography forming the mother’s background is subdued, almost ghostlike, as if the artist wanted to invest her with an ethereal presence. The religious imagery is an extension of their bodies, both protecting and empowering them.

In contrast, the artist depicts himself in the clouds, almost levitating. He awkwardly balances a flower pot of forget-me-nots over an old, studded suitcase in one hand, and the picture of his grandfather in another. Signs of an idyllic nature bloom in the background, his smiling children safely ensconced in the greens, the sky overhead, waterfalls to his side; he appears to be in a conceptual heaven.

Tehran-based artist Khosrow Hassanzadeh had previously used members of his family as models (Old Paintings). In his latest exhibition at Silk Road Gallery he has come up with a new twist. Attached to each work is a tag that carries the label “Terrorist” and bears such information as name, nationality, religion, age, distinctive traits, and personal history of the four characters portrayed.

Hassanzadeh first gained international recognition with War (1998), a grim and trenchant “diary” of the eight year Iran-Iraq conflict. In Ashura (2000), an interpretation of the most revered Shia religious ceremony, the artist depicted chador-clad women engulfed by calligraphic forms and religious iconography. Chador (2001) and Prostitutes (2002) continued his exploration of sociological themes particular to Iran’s hyper-gendered urban landscape. The latter used police mug shots and the serigraphy technique to pay tribute to the 16 prostitutes killed by a serial killer in Mashhad, a religious capital of Iran.

The artist’s critical treatment of sacred themes initially set him apart from state artists who readily accepted and glorified them. He moved further away from both state and Iranian high society artists with his work on women. Increasingly, his art came to address an outside observer. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Prostitutes, where he sides with a dominant western view of eastern backwardness.

But this was an uneasy relationship. The artist’s search for an “indigenous” solution resulted in Pahlavans (2003), silkscreen reproductions of old photographs of traditional wrestlers who, according to the artist, “took care of the vulnerable people in society and were deeply respected.” In 2001, Hassanzadeh began working on a series of portraits of western women that he tentatively called Occidentalist. He returned to the work in progress two years later, this time using the serigraphy technique rather than paint. By representing western women’s exposed bodies the artist attempted to return the gaze. Though this collection was never shown publicly, with the Occidentalist, the occident saw its body through an Oriental lens.

Hassanzadeh’s Terrorist women stare back with a placid patience. They are neither sad nor happy, deviant nor pliant, calm nor angry, sane nor mad. They are independent of their beholder, while they defy interpretation. The image of the artist, however, is different. His bulging eyes are recalcitrant and directed toward the spectator.

The six-piece silkscreen exhibit is impressive in its execution and final effect. The difficulty of working with the medium on such a scale is akin to muscle-flexing (the artist had to work and rework the stencil with lapidary exactitude). At the same time, it compellingly co-opts a medium often used in government-sponsored posters and affiches. Further, the portraits eerily resemble images of Taliban and Al-Qaeda terrorists posted on the Internet.

Standing before the Terrorist, the (western) spectator is dwarfed by the size of the works, unable to interpret the enigmatic look on the subjects’ faces. The imaginary landscape, rife with culture-specific symbolism, points to an unknown world with sinister implications. The image of the artist at once fascinates and overwhelms the viewer’s gaze. In the end, Terrorist is arguably a continuation of the Occidentalist project, exposing the potential for violence embedded within the western representational model.