“To leave is romantic, to return is baroque.”

—Anton LaVey

There are only so many ways to riff on the image of the World Trade Center. That was true before September 11; it remains true today. You can do the math: add a tower, remove one, take both away. A lot of people fantasized about getting rid of them, long before Khalid Sheikh Mohammed or whoever dreamt of using airliners to do the job, though the actual circumstances of the WTC’s destruction were not quite what they had in mind. Party Music, an album by the Marxist hip hop group The Coup, had to be postponed in late September 2001 because the original cover art featured group members, DJ Pam the Funkstress and Raymond “Boots” Riley, a fake detonator in hand, the Twin Towers exploding overhead. They had worse timing than most, but they were far from alone.

In death as in life, the creation of Japanese-American architect Minoru Yamasaki has served as a twin engine of fantasy.

The towers at The World Trade Center were the foremost architectural statement of surplus glory. Despite their slightly differential height — the North Tower required a few extra feet for a cafeteria on the 43rd floor — they were clearly the same building, twice. Not only the tallest building in the world (an ambition hatched not by the architect but by the Port Authority public relations office), it was the tallest building and its uncanny echo — its shadow or doppelganger. Or rather, its clone. In his 1983 essay “Simulations” Jean Baudrillard rhapsodized that the second tower canceled out the first, signifying “the end of all original reference….For the sign to be pure, it has to duplicate itself: it is the duplication of the sign that destroys its meaning.”

This was not untrue; the second tower by its nature gave the lie to the first. But what was the lie? What was lost in the duplication? For Baudrillard each single building is an “effigy of the capitalist system,” a “pyramidal jungle, all of the buildings attacking each other”; the Twin Towers spelled “the end of all competition” as well as “the end of verticality.” It also spelled the end of an era in architecture: the Towers were “blind. … All referential of habitat, of the façade as face, of interior and exterior, that you still find in the Chase Manhattan or in the boldest mirror-buildings of the ‘60s, is erased.”

As was his wont, Baudrillard cast his analyses in extremis. History has just ended. Everything has always just ended. But he was, again, not wrong. Seen from a certain angle, against the sun, the Towers lost their specificity, their gothic flourishes; they became mute, undifferentiated. They did not come after the end, but before the beginning.

The monolith derives its power from its singularity: it is “carved from one stone,” and was associated with transformation long before Kubrick’s 2001 — that is, before 1969. And not in a good way. The first appearance of the monolith in the film betokens the discovery of technology, the leap from ape to human: to Homo Sapiens as Homo Faber, “man the maker,” and also, at the same moment, Homo Necans, “man the killer.” That the first tool should become the first murder weapon would not surprise an alchemist.

The destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 finalized the concatenation of the Twin Towers, forever fused into a singular entity. An accident of history with the force of finality; it is as though one thing is gone, not two. It is almost impossible to imagine it otherwise, to conceive of what New York would look like, say, if United Airlines Flight 175 had missed its target. If the monument to the WTC were a single tower, forever mourning its absent twin. Donald Trump’s quixotic campaign to rebuild an exact duplicate of the Twin Towers may make more sense than the decision to build them in the first place. There was always something volatile about this doubling, the twoness of the twins. Sometimes, as Mahogany says, “One Plus One Equals Three Or More.” When the Word became Flesh, when the Father begat the Son, He also begat the Holy Spirit, a third force, invisible but also indivisible: triune, three-in-one. Bidoun’s Trinity Towers, now open for business.

Or, it’s just a joke.

We lifted the idea from The 80s: A Look Back at the Tumultuous Decade, one of the best-selling books of 1979 and the kind of book you can find for a dollar on the streets of New York today. The 80s was a piss-take on “popular histories,” the brainchild of veterans of Sesame Street, Monty Python, and National Lampoon. It chronicled a variety of outlandish prospects, from the acquisition of the United Kingdom by the Disney Corporation in 1981 to the invasion of Europe by Arabs in 1989. Midway through the decade, on p. 160, the iconic Twin Towers of the World Trade Center acquired a sibling: a third tower, standing on the twins’ shoulders, like cheerleaders, the better to accommodate the booming business in commodity futures.

Not a very good joke, really. But the image also raised a perfectly fine question: why not three towers? Yamasaki faced just such a question at the press conference in 1972, at the completion of the WTC. Why two 110-story buildings? he was asked. Why not a single tower 220 stories tall? “I didn’t want to lose the human scale,” the architect said.

That was a joke, too. The International Style never seemed so stark or brooding as in the rectilinear tablets of the WTC. Lewis Mumford decried its “purposeless gigantism and technological exhibitionism.” Occupants complained about the narrow vertical windows, gothic accoutrements of Yamasaki’s imagination. When Philippe Petit made his famous tightrope walk in 1974, it signified precisely the stark contrast between the towers — not merely buildings, but monuments — and the human.

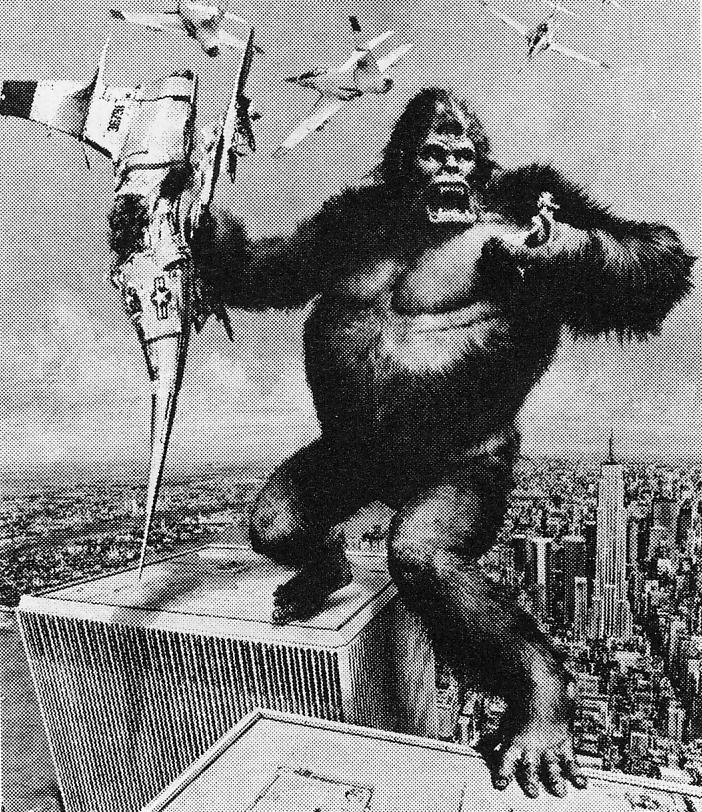

At the end of the original 1933 version of King Kong — an allegory of miscegenation, Hitler’s favorite film — the transplanted gorilla from Skull Island clung precariously to the single spire of the Empire State Building, the tallest in the world, completed only two years earlier. In the 1976 remake, the doomed ape found a more comfortable purchase by standing astride the Twin Towers. There was something right about it; the scale was correct. The advertising campaign for the remake was the first to feature the towers as a design element: an outsized Kong, bristling with rage, crushing an incoming plane in his tense black fist.

As it happened, the iconic part of the poster was the plane, not the ape.